Scientists watch in unbelievable detail as galaxy smashes into another at two million miles per hour

The impact was observed in Stephan’s Quintet, a nearby galaxy group made up of five galaxies.

Scientists have watched in unprecedented detail as galaxies smashed into each other at two million miles per hour.

The team used one of Earth’s most powerful telescopes to observe as galaxies collided with each other.

When the two struck each other, they let out a shockwave similar to that made by a jet fighter when it reaches the speed of sound. That is among the most powerful phenomena in the universe.

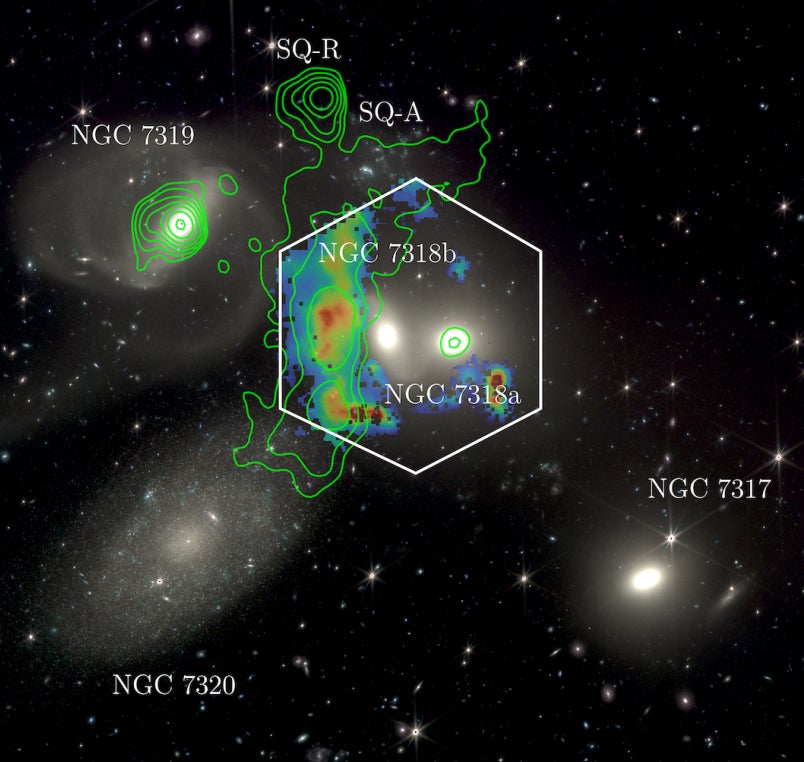

It was observed in Stephan’s Quintet, a nearby galaxy group made up of five galaxies first sighted almost 150 years ago.

A team of scientists led by the University of Hertfordshire captured the event using the new 20 million euro William Herschel Telescope Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer (Weave) wide-field spectrograph in La Palma, Spain.

Dr Marina Arnaudova said: “Since its discovery in 1877, Stephan’s Quintet has captivated astronomers, because it represents a galactic crossroad where past collisions between galaxies have left behind a complex field of debris.

“Dynamical activity in this galaxy group has now been reawakened by a galaxy smashing through it at an incredible speed of over two million miles per hour, leading to an immensely powerful shock, much like a sonic boom from a jet fighter.”

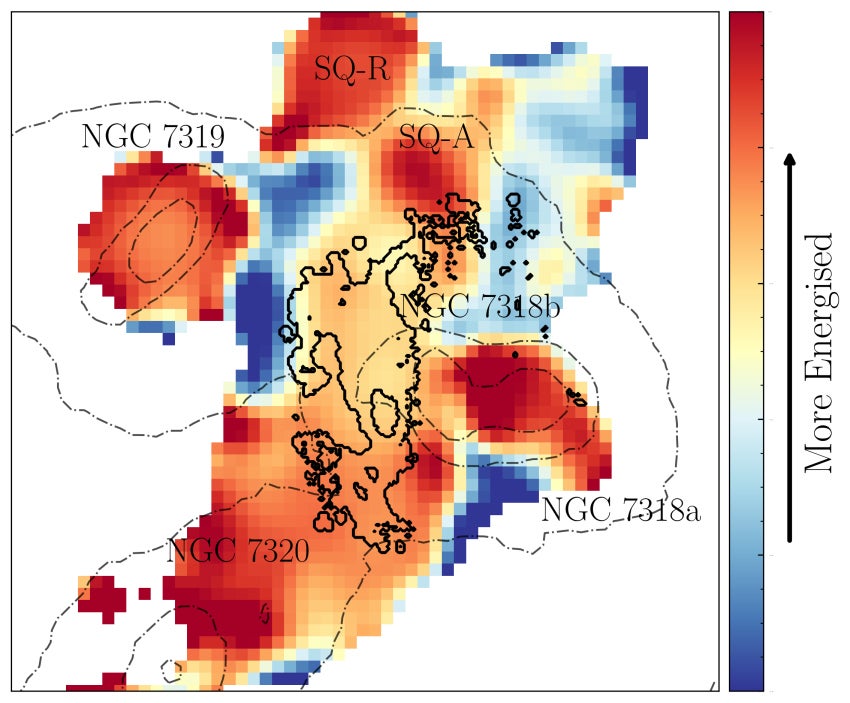

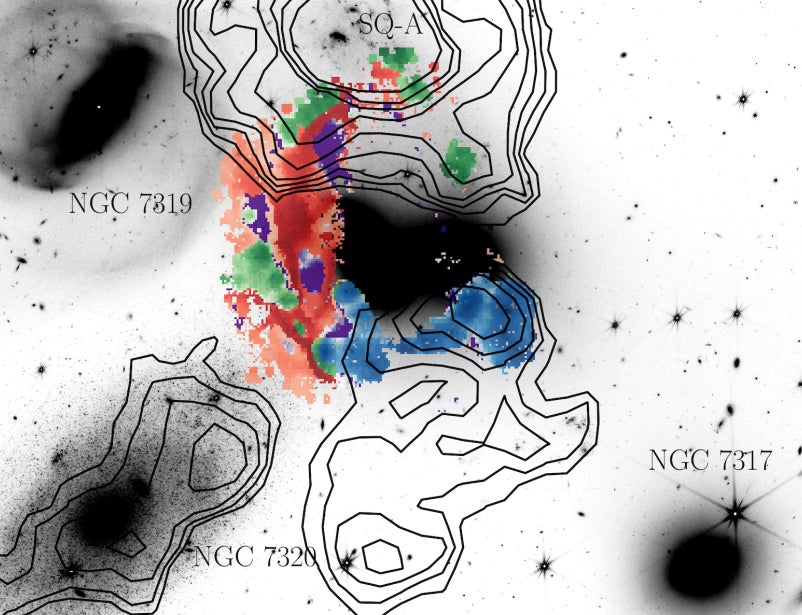

The researchers uncovered a dual nature behind the shock front, previously unknown to astronomers.

They found that as the shock moves through pockets of cold gas, it travels at hypersonic speeds, powerful enough to rip apart electrons from atoms, leaving behind a glowing trail of charged gas.

However, when the shock passes through the surrounding hot gas, it becomes much weaker, according to PhD student Soumyadeep Das, of the University of Hertfordshire.

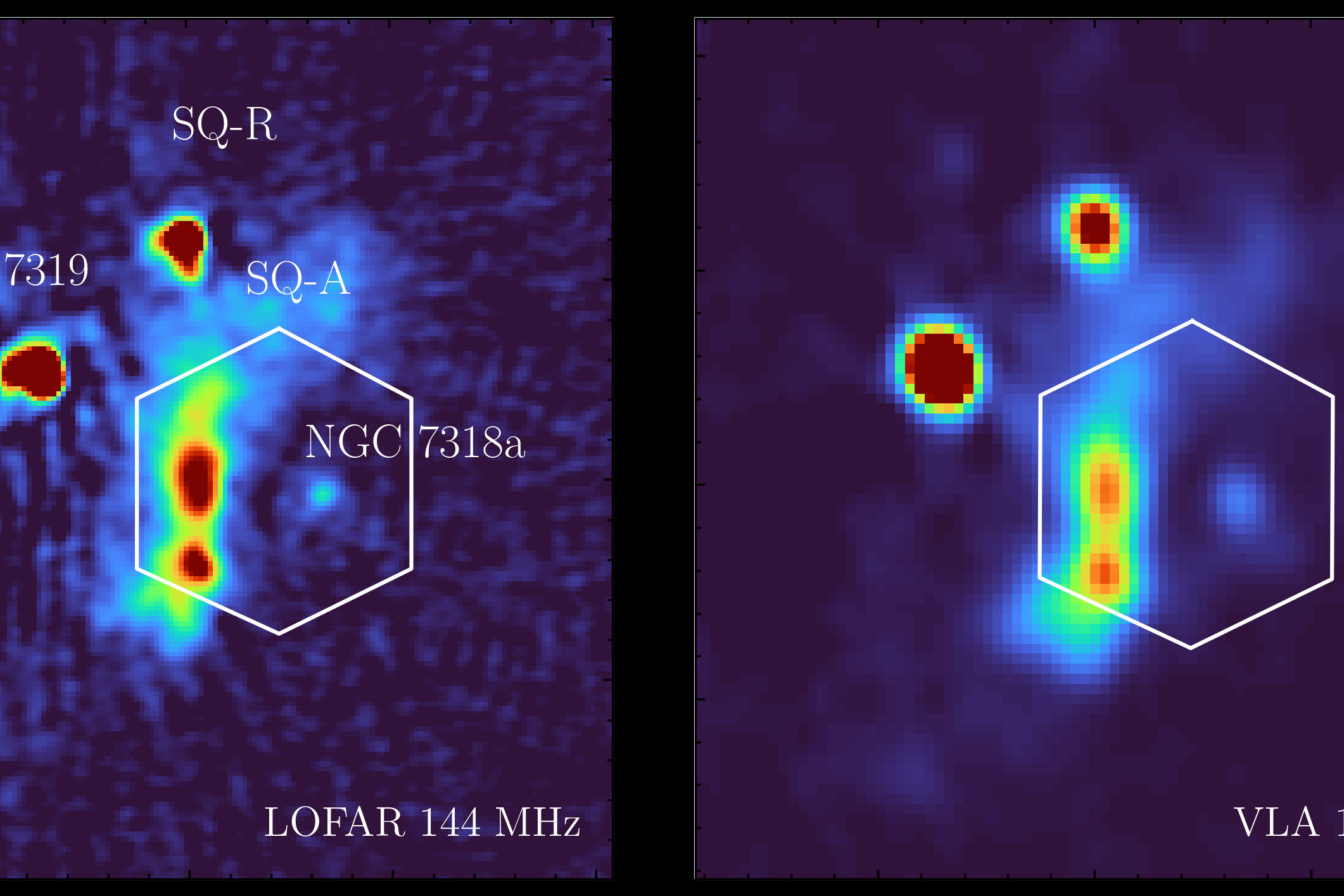

He added: “Instead of causing significant disruption, the weak shock compresses the hot gas, resulting in radio waves that are picked up by radio telescopes like the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR).”

The new insight and unprecedented detail came from Weave, combining data with other cutting-edge instruments, and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

The findings are published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society journal, and researchers believe that Weave is set to revolutionise our understanding of the Universe.

Additional reporting by agencies