Gaia mission detects unexpected ‘starquakes’ while mapping 2 billion stars

The third data release from the European Gaia mission shows the space telescope is more sensitive than expected while it builds a map of our galaxy

The newest data release from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission brought scientists a surprise: The space telescope detected starquakes, something the space-based telescope wasn’t designed to see.

“Starquakes teach us a lot about stars, notably their internal workings,” astrophysicist Conny Aerts of KU Leuven in Belgium, part of the international team behind Gaia, said in a statement. “Gaia is opening a goldmine for ‘asteroseismology’ of massive stars.”

The third and newest data from Gaia,, released on Monday, also includes detailed mapping and spectrometry data on more than 2 billion stars.

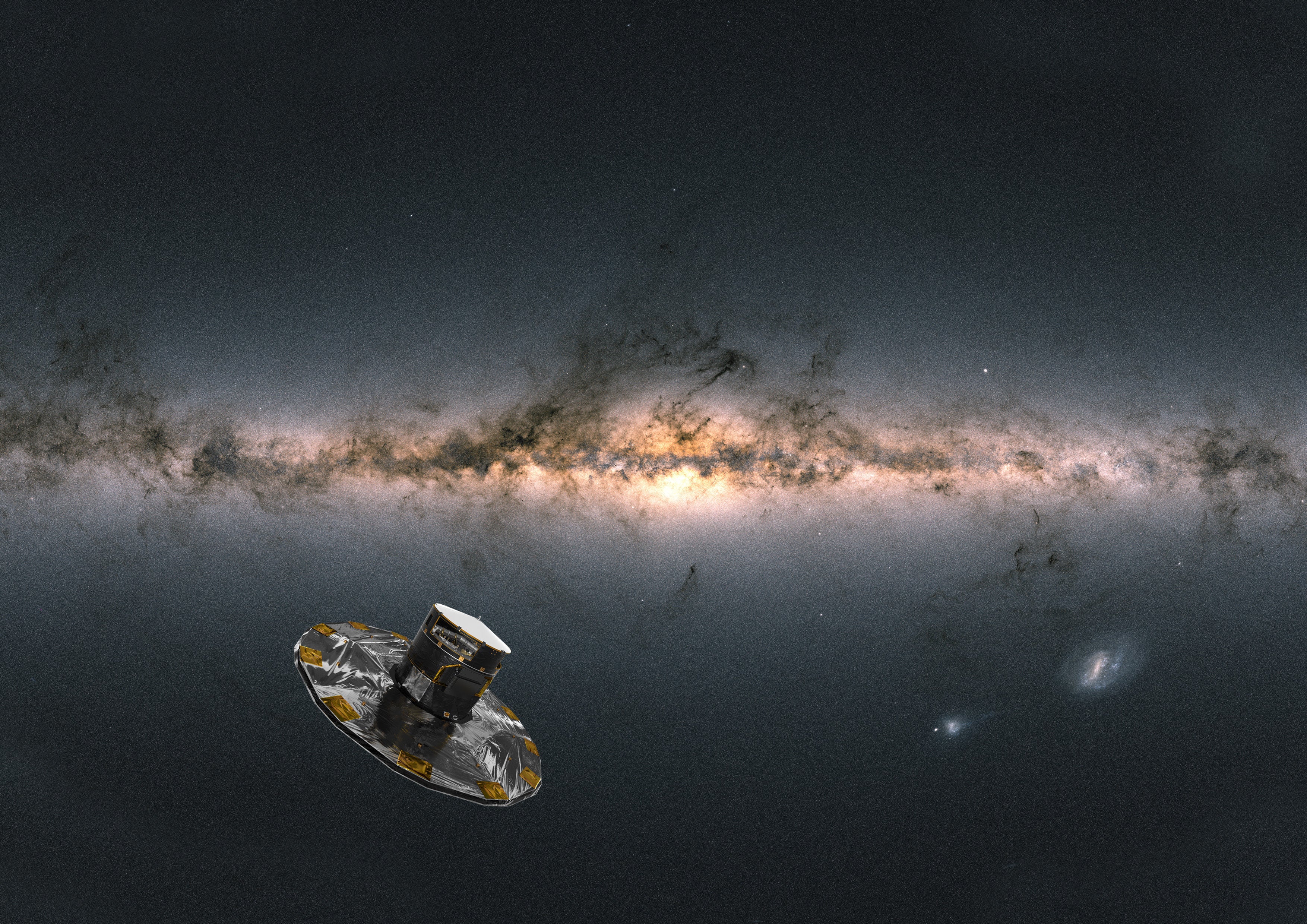

Esa launched Gaia in 2014 with a mission to create a detailed, multi-dimensional map of our Milky Way galaxy, charting not only the locations of celestial objects such as stars and exoplanets, but their velocities and spectra as well. Like the James Webb Space Telescope, it orbits around Lagranian Point 2, a location about 1.5 million kilometers behind Earth as seen from the Sun.

The first Gaia data was released in 2016, and contained luminosity and location data on more than 1 billion stars. The second data release in 2018 increased the total number of stars charted by Gaia to 1.7 billion stars, and added additional detail on their movements — Gaia will monitor stars and other objects over time to understand their motion and how it relates to the galaxy as a whole.

In addition to capturing starquakes — tsunami-like waves on stellar surfaces that actually change a star’s shape — the new data release provides the largest ever chemical map of the galaxy, mapping star’s constituent elements as well as their locations and velocities. Researchers can now use the chemical signatures of stars, for instance, how many of the heavier metallic elements produced by the explosions of other, dying stars, to help identify them. Such chemical fingerprinting allowed Gaia researchers to identify some intergalactic interlopers, stars that came from other galaxies and were somehow incorporated into the Milky Way.

“Our galaxy is a beautiful melting pot of stars,” Gaia collaboration member and galactic archeologist Alejandra Recio-Blanco of the Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in France, said in a statement. “This diversity is extremely important, because it tells us the story of our galaxy’s formation. It reveals the processes of migration within our galaxy and accretion from external galaxies.”

Gaia has also created a catalog of more than 800,000 binary star systems, mapped molecular clouds between stars, and charted 156,000 rocky bodies in and around our Solar System. And its detailed survey of out galaxy could help identify important targets for follow up by the newly commissioned James Webb Space Telescope.

“Unlike other missions that target specific objects, Gaia is a survey mission,” Esa Gaia project scientist Timo Prusti said in a statement. “This means that while surveying the entire sky with billions of stars multiple times, Gaia is bound to make discoveries that other more dedicated missions would miss. This is one of its strengths, and we can’t wait for the astronomy community to dive into our new data to find out even more about our galaxy and its surroundings than we could’ve imagined.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments