Earth’s core is twisting under our feet, scientists find

Scientists were surprised to Earths core doesn’t keep pace with our planet’s surface, and sometimes spins in the opposite direction

Earth’s core doesn’t rotate in sync with the rest of our planet, but instead spins faster at times, and at others reverses direction.

That’s the finding of new research published Friday in the journal Science Advances by Southern California seismologists John Vidale and Wei Wang.

“The inner core is not fixed,” Dr Vidale said in a statement. “It’s moving under our feet, and it seems to go back and forth a couple of kilometers every six years.”

It’s a finding that could help scientists better understand how Earth’s core generates the geomagnetic field that blocks radiation from space and makes life possible, and might explain why the length of the day fluctuates over time.

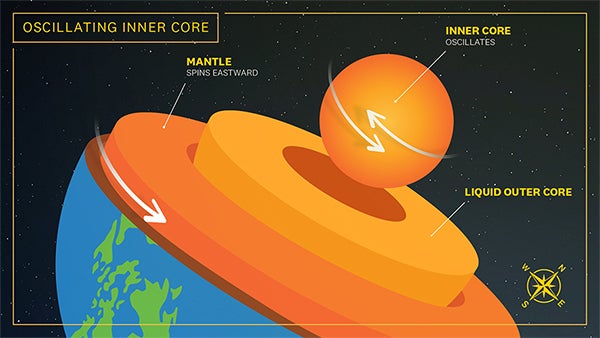

Inside to outside, Earth consists of a solid inner core surrounded by a liquid iron outer core, a thick rocky mantle, and then the thin crust and atmosphere where life exists.

At more than 6,300 kilometers beneath the surface, the inner core is inaccessible, and geoscientists must infer its properties and behavior through indirect measurements and its effects. They know the inner core spins, for instance, because the solid metal spinning within the liquid metal outer core is the geodynamo that generates the planet’s magnetic field.

But for decades, scientists have puzzled over data that suggested the inner core might shift its speed of rotation compared to the surface.

“From our findings, we can see the Earth’s surface shifts compared to its inner core, as people have asserted for 20 years,” Dr Vidale said in a statement. “However, our latest observations show that the inner core spun slightly slower from 1969-71 and then moved the other direction from 1971-74.”

From 1968 through 1971, the planet’s inner core sub-rotated, spinning West relative to the Earth’s mantle and crust. From 1972 into 1974, the inner core super-rotated, spinning Eastward faster than the crust and mantle.

Dr Vidale added that the change in inner core spin correlates with a millisecond scale change in the length of the day researchers have independently observed taking place over a six year period. The day shortened by 0.01 milliseconds during the period of inner core sub-rotation, and lengthen by up to 0.12 milliseconds during the period of super-rotation.

Because the inner core is inaccessible for direct measurement, Drs Vidale and Wang looked at seismic waves bouncing off of the inner core to measure its speed and direction of its rotation. Specifically, they looked at recordings of the reflections of seismic waves generated by nuclear bomb tests in the former Soviet Union from 1971 to 1974, and two tests conducted by the US in Alaska in 1969 and 1971.

These historical data were recorded using the Large Aperture Seismic Array in Montana, more than 300 geophones buried 60 meters deep in the ground and used to listen to seismic waves to determine if they were Earthquakes or atomic detonations.

Detonations generate waves which are scattered and reflected back by the solid inner core, with waves scattered by a portion of the core spinning away from the receiving geophone arriving later than waves scattered by parts of the core spinning toward the geophone. This allowed Drs Wang and Vidale to calculate the inner core’s direction and speed of rotation.

It was a surprising result, Dr Vidale said, the idea that the inner core might oscillate in its rotation just one theory among many before their new study.

“The idea the inner core oscillates was a model that was out there, but the community has been split on whether it was viable,” he said in a statement. “We went into this expecting to see the same rotation direction and rate in the earlier pair of atomic tests, but instead we saw the opposite. We were quite surprised to find that it was moving in the other direction.”

More research is needed, but could be hampered by the lack of precisely located seismic waves, given that the US and Russia ceased testing nuclear weapons in the 1990s. But the study shows historical data can still shed light on the inner workings of the Earth.

“We're trying to understand how the inner core formed and how it moves over time,” Dr Vidale said in a statement. “This is an important step in better understanding this process.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks