Stargazing in October: The comet is coming!

Be prepared for the most spectacular cometary visitor for northern climes since Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997, Nigel Henbest writes

Next week look out for the most spectacular sky-sight of the year, as Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS hangs like a glowing dagger in our western skies after the Sun has set – the most spectacular cometary visitor for northern climes since Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997.

Astronomers at the Purple Mountain (Tsuchinshan) Observatory in China first found a faint object far from the Sun on 9 January 2023. At the end of the following month, it showed up on images taken by the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope in South Africa – hence the double-barrelled name.

Its orbit shows that Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS was last near the Sun – and visible from the Earth – over 80,000 years ago, around the time that humans left Africa. This ball of ice and rock then travelled way out to the frozen wastes of the outer solar system; and now it is on its way back. As it heads towards the Sun’s heat, the ices have been boiling away, to release gas and dust that’s now forming a huge glowing head and a long shining tail.

Early this summer, there were worries that the comet’s solid nucleus was disintegrating, and it would totally fall apart before reaching the Sun. But comets are like cats: they have tails, and do whatever they want. In reality, the nucleus of Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS has held together, even as it rounded the Sun on 27 September at a speed of 240,000 kilometres per hour.

Last weekend, I caught a glimpse of the comet as a faint smudge low in the east before sunrise. Astronomers further south have had a more favourable perspective of the comet in the dawn sky, and they have posted some stunning images online. The astronauts on board the International Space Station have snapped some unique shots of Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS hanging above the Earth.

Though the comet has so far been best seen from the southern hemisphere, that’s all set to change as Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS speeds past the Earth on 12 October, at a distance of 71 million km. From that date on, the comet is visible from the northern hemisphere in the evening sky, rising higher it the sky night by night.

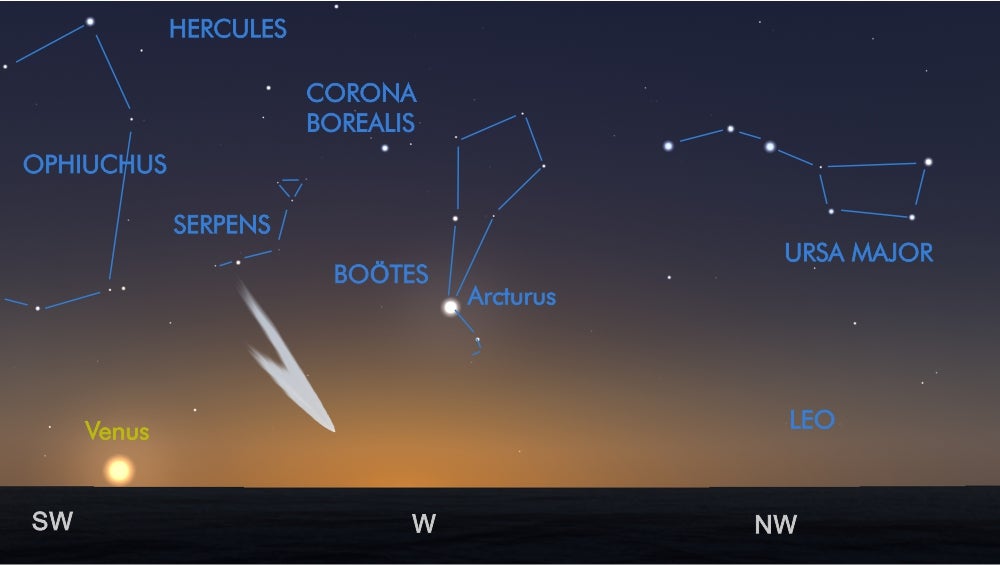

To find the comet, look towards the south-west and you’ll spot the brilliant planet Venus. Scan the sky to the right, and you should find the comet between Venus and the bright star Arcturus. The comet sets before the time of my usual monthly starchart (11 pm BST), so I’m dropping in a – perhaps rather optimistic – chart of the horizon view on 12 October.

I say optimistic’ because no-one knows yet how brilliant the comet will appear. A straightforward calculation would make the comet fainter than Arcturus. But I am buoyed by the fact that the comet has been shedding huge quantities of dust into its fuzzy head and trademark tail. As the comet swings between the Sun and the Earth, the dust should scatter extra sunlight in our direction and hence appear a lot brighter than we’d expect – just as dust on your car’s windscreen is distractingly bright as you drive into the Sun. If we are that lucky, Comet Tsuchinshan–ATLAS could appear more brilliant than any of the stars, outshone only by Venus and the Moon, and sporting a glorious tail.

Even if the comet refuses to match these predictions, we are in for a treat this month. Check out in advance a place with a low western horizon, and away from any brilliant artificial lights; arm yourself with binoculars or a telescope for a close-up view; and keep a vigil after sunset for a sky-sight that you will never forget.

What’s Up

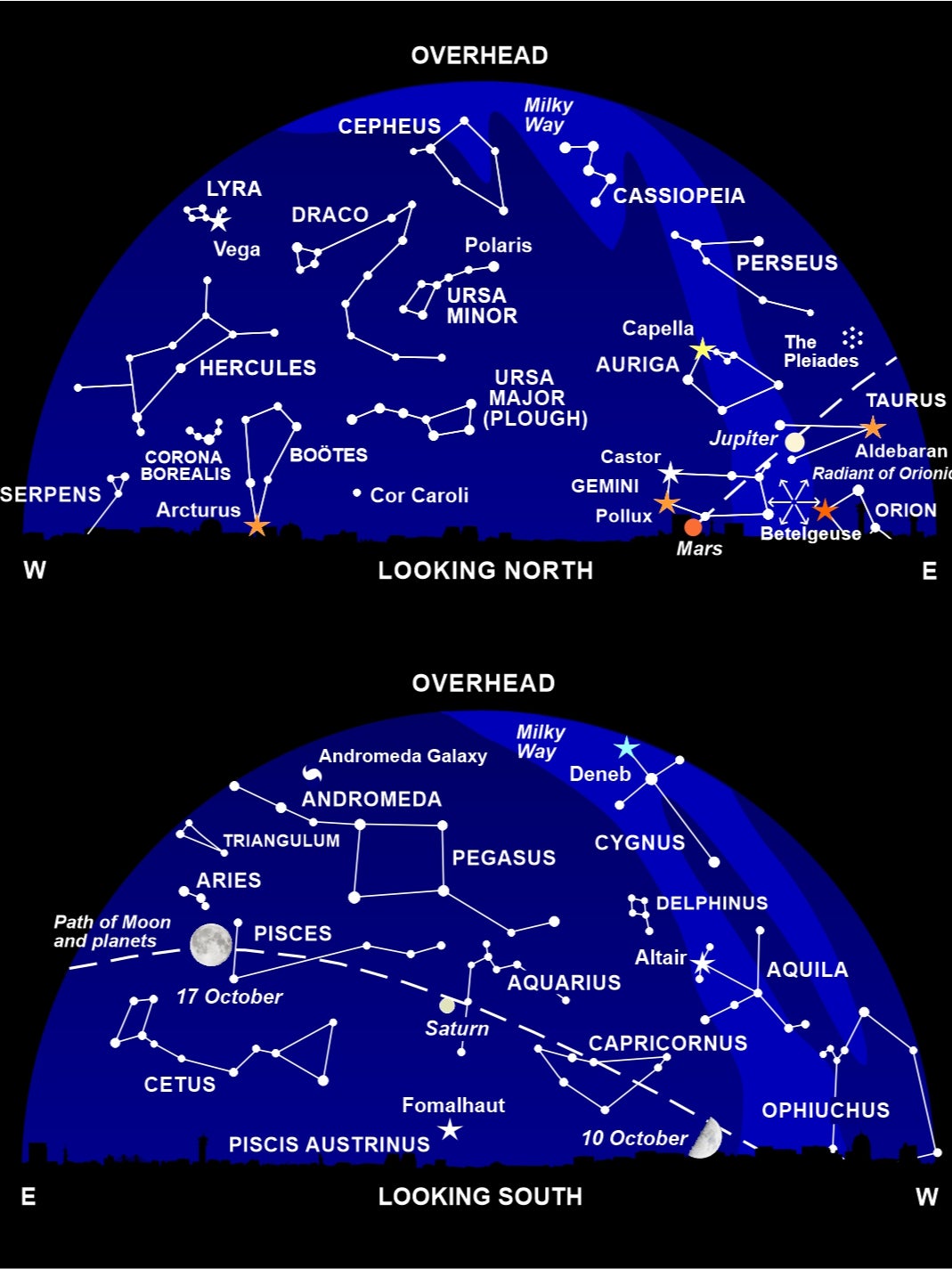

Catch Venus low in the south-west soon after sunset; it forms a lovely duo with the crescent Moon on 5 October, though you may need binoculars to spot the pair against the bright twilight glow.

Saturn is shining in the south for most of the night, the brightest spark in a region of faint stars. The Moon glides right under the ringed planet on the evening of 14 October. The star below Saturn – just skimming the horizon – is Fomalhaut, the most southerly of the 20 brightest stars to be visible from the British Isles, and for me the harbinger of autumn.

Over the in the north-east, Jupiter shines more brilliantly than any of the stars in the midst of the constellation Taurus (the celestial bull). To its upper right you’ll find the twinkling Pleiades, a star cluster known poetically as the Seven Sisters. On the evening of 19 October, the Moon passes over the lower fringes of the Pleiades and hides several of its fainter stars.

Mars lies to the lower left of Jupiter in Gemini. It’s around 15 times fainter than the giant planet, and shines with a distinctly orange-red hue. By the end of October the Red Planet lines up with the twin stars Castor and Pollux.

The October Full Moon is traditionally known as the Hunter’s Moon, and this year it’s certainly set to help anyone out-and-about after dark – whatever their business – as the Full Moon on 17 October is the best supermoon of 2024, nearer, bigger and brighter than any other Full Moon this year.

Less spectacular will be the annual Orionid meteor shower, peaking on 21 October, as our view of its shooting stars will be washed out by bright moonlight.

5 October: Moon near Venus

7 October: Moon near Antares

10 September: Moon near Antares

10 October, 7.55pm: First Quarter Moon

12 October: Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS nearest the Earth

14 October: Moon near Saturn

17 October, 12.26pm: Full Moon; supermoon

19 October, 7.30pm to 10.30pm: Moon occults the Pleiades

20 October: Moon near Jupiter

21 October: Moon near Jupiter; maximum of Orionid meteor shower

23 October: Moon near Mars, Castor and Pollux

24 October, 9.03am: Last Quarter Moon

27 October: BST ends

Nigel Henbest’s ‘Stargazing 2025’ (Philip’s £6.99) is your monthly guide to everything happening in the night sky next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks