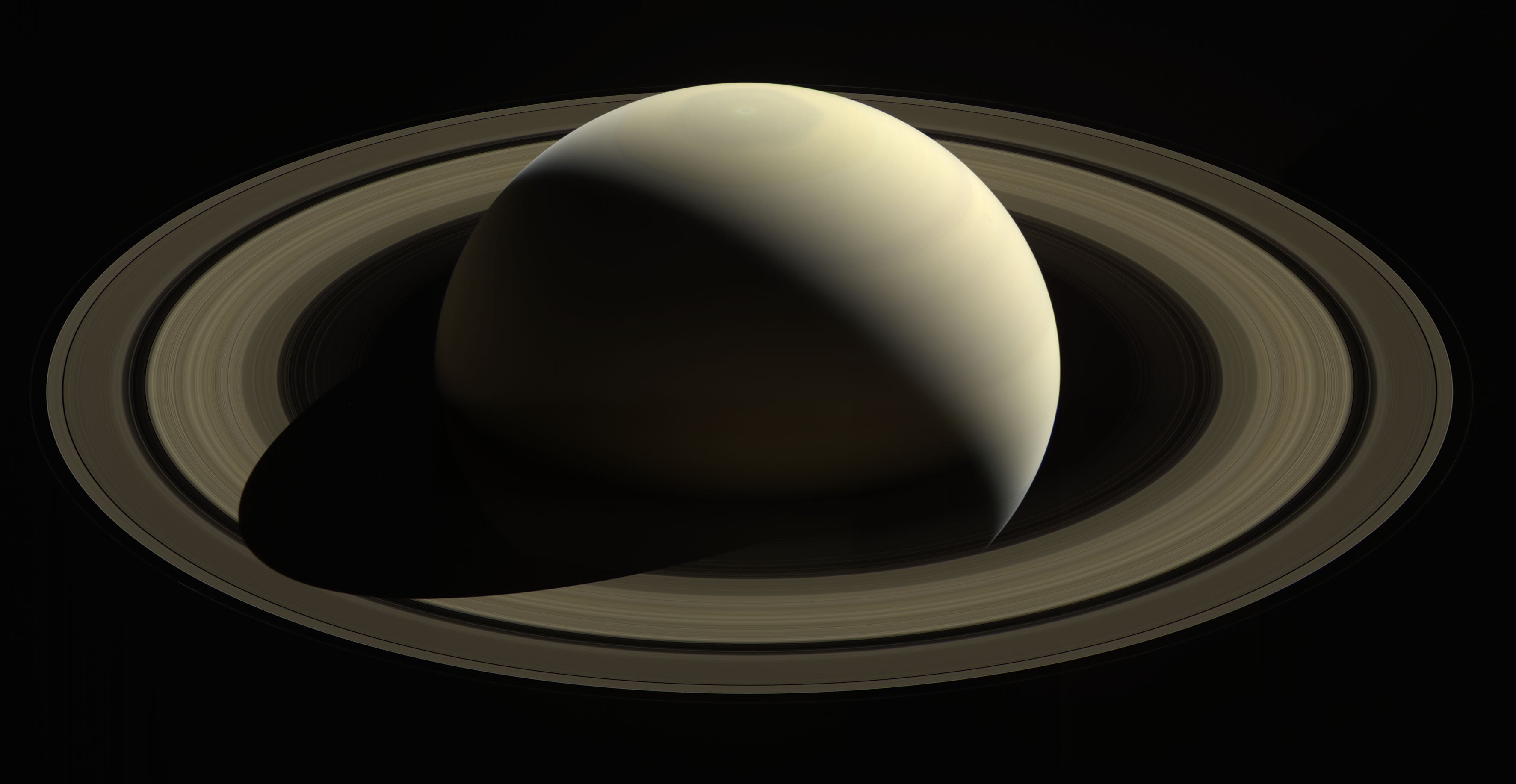

Missing moon may be answer to how Saturn got its rings

Scientists believe a ‘grazing encounter’ ripped the satellite apart, with some of the debris giving rise to the planet’s signature rings.

The answer to the mystery of how Saturn got its famous rings may lie in a moon that went missing millions of years ago, according to scientists.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US believe that this moon, named Chrysalis, orbited the ringed planet for several billion years until it was violently ripped apart 160 million years ago.

The findings, published in the journal Science, are based on observations from Nasa’s Cassini spacecraft, a probe sent to study Saturn.

The data from Cassini, which was destroyed in 2017, allowed the scientists to run simulations and understand more about Saturn’s orbit, tilt and composition.

Jack Wisdom, professor of planetary sciences at MIT and lead author of the new study, said: “Just like a butterfly’s chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged.”

Saturn is host to 83 moons but the researchers believe that around 160 million years ago it had an extra satellite.

Analysis based on the computer models suggest Chrysalis orbited the planet with its 83 siblings, pulling and tugging on the planet in a way that kept its tilt in resonance with its neighbouring planet, Neptune.

Then around 160 million years ago, Chrysalis became unstable and came too close to its planet, in a violent “grazing encounter” that ripped the satellite apart, with some of the debris giving rise to Saturn’s signature rings.

The loss of Chrysalis was enough to remove Saturn from Neptune’s grasp and leave it with the tilt that is present today, researchers said.

They add that this missing moon theory could also explain why Saturn’s rings are only around 100 million years old – much younger than the planet itself at 4.5 billion years.

Saturn’s rings weigh about 33 million trillion pounds and are made almost entirely of ice — about 95% of which is pure water while the rest is rock and metals.

The rings are thought to be fading over time as the particles within are colliding with each other, causing them to spread out.

The researchers said more studies are needed to confirm their findings.

Prof Wisdom said: “It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others.

“But it seems that this lost satellite was just a chrysalis, waiting to have its instability.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks