Stargazing July: Mars outshines Jupiter in its brightest moment for 15 years

Later this month, the red planet is in line with the Sun and the Earth and also the eclipsed Moon

This July is a magic month for stargazers. The warm weather invites you to marvel at the heavens – and on the night of 27 July, you’re in for a double treat.

First, there’s a total eclipse of the Moon. And it lies immediately above Mars, which is closer and brighter than it’s been in 15 years, outshining even Jupiter over in the southwest.

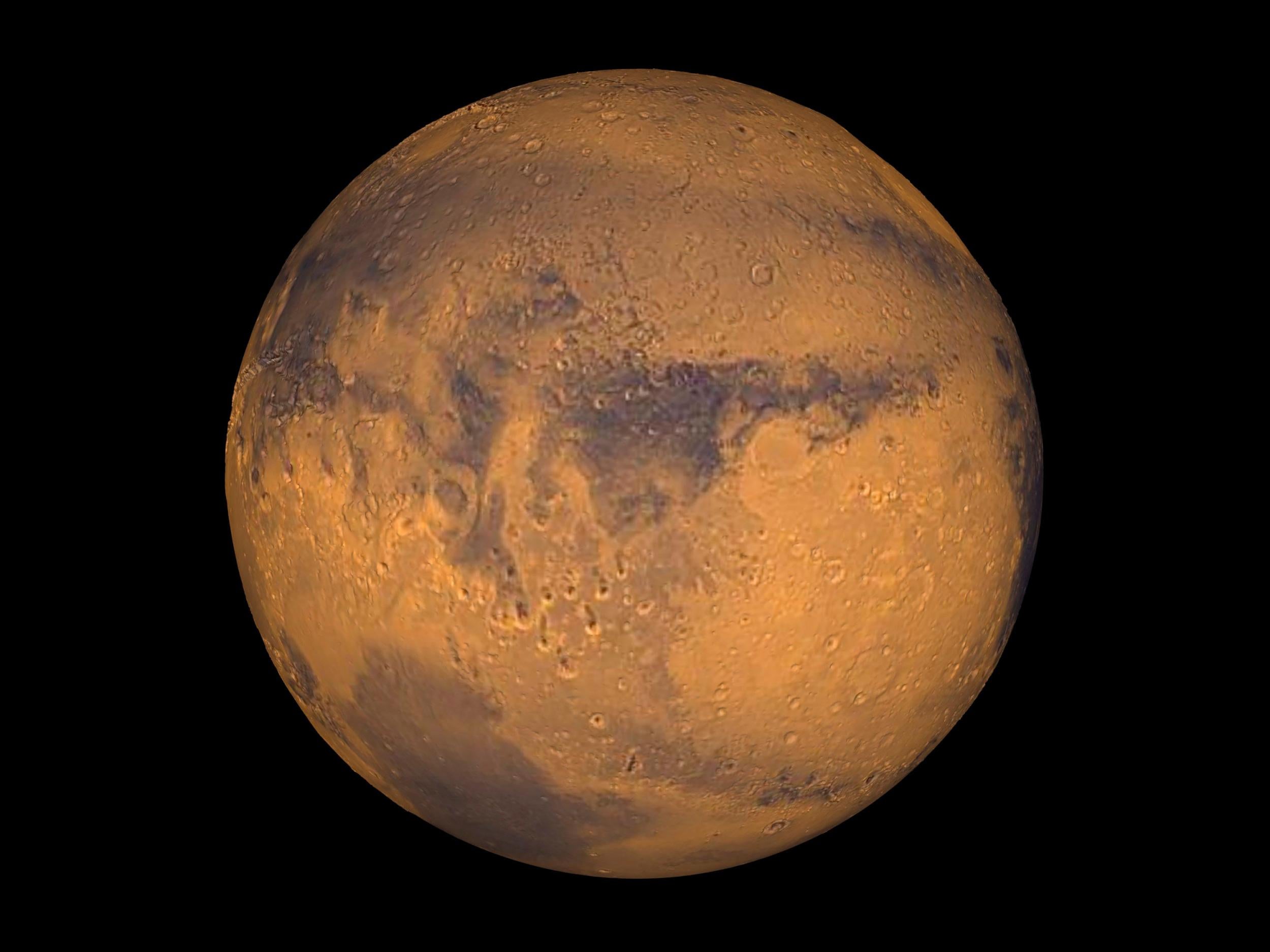

The red planet is a beautiful sight through a medium-sized backyard telescope. Although just half the size of the Earth, Mars has a lot in common with our world.

Polar caps, made of snow and carbon dioxide ice; are a thin atmosphere laced with fluffy clouds and dark markings once thought to be vegetation (they turned out to be dark rocks instead).

All this has encouraged the space community to search for life on Mars. Dozens of missions have been sent to the red planet, including Britain’s Beagle 2 probe in 2003.

The much-loved spacecraft landed successfully, but failed to deploy all of its solar panels to communicate with Earth.

Nasa had a better time with its twin Viking probes, which landed in 1976. They both contained four experiments to detect signs of life. One of the four came out positive. We’re not talking about little green men here, more like little green slime!

Gil Levin’s Labelled Release experiment was a Martian version of a procedure he had conducted successfully for many years on Earth, which searched for Legionnaires’ Disease bacteria in air conditioning systems.

The process? Feed bugs something delectable; like babies, they burp. Lace the nutrient with a dash of radioactivity, and you can detect even tiny quantities of gas being emitted. And that’s what Levin found.

We saw his data at first hand, and they were identical to the curves of emissions he’d gathered on Earth.

But Nasa was having none of it. Their main experiment – to detect carbon atoms in the Martian soil – came up with none. So, if there was no carbon, there couldn’t be life. Levin was dismissed as being merely a “sanitary engineer” and Nasa maintained its official stance.

Years later, we interviewed other scientists about Nasa’s failure to find carbon. “Oh – THAT experiment,” they said. “It was so insensitive that it would have missed 30 million bacteria cells per gram of soil”.

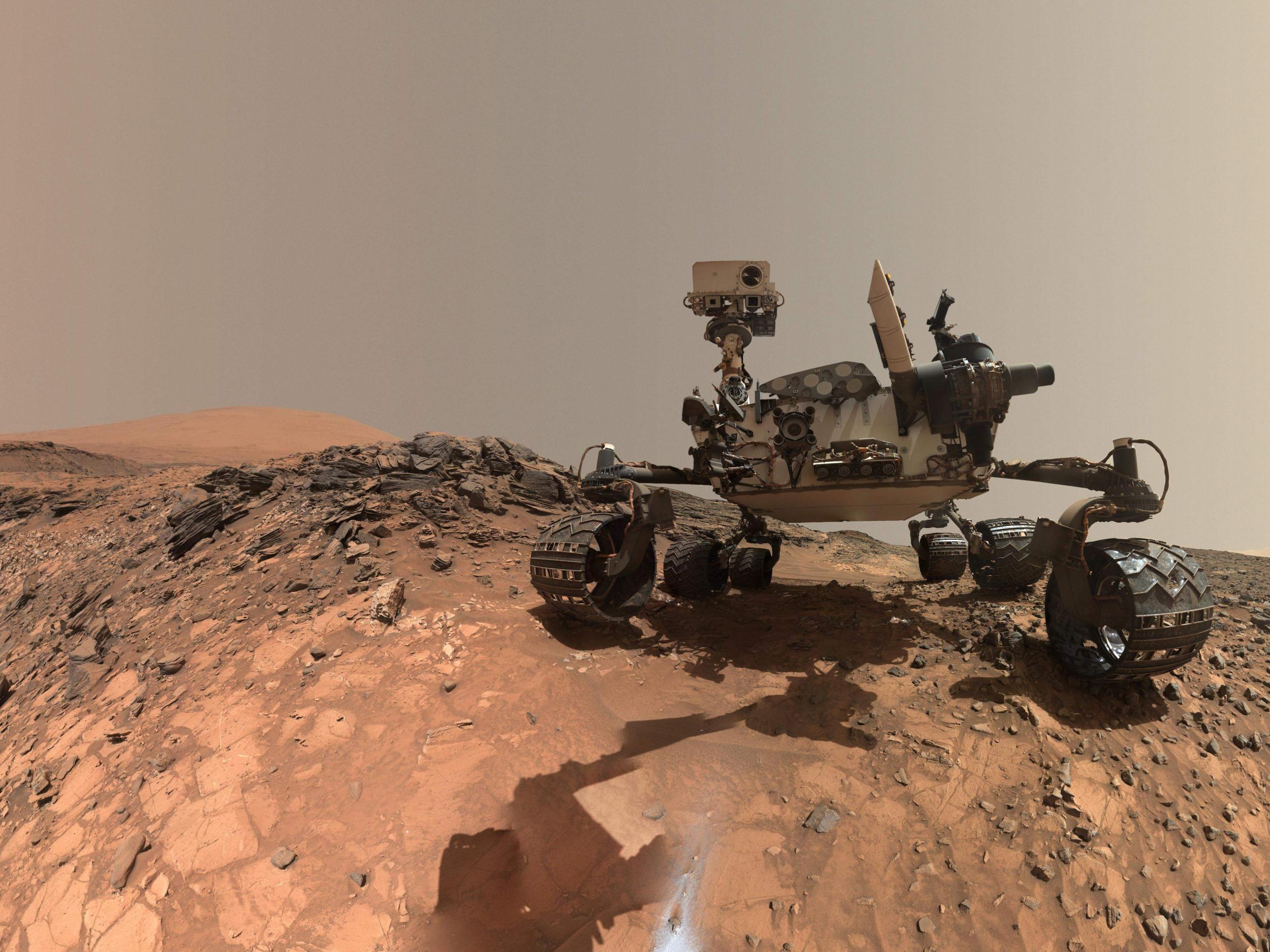

Nasa now appears to be waking up. Their car-sized rover, Curiosity, landed in the 154km-diameter Gale Crater in 2012. The rover was named by 12-year-old Clara Ma from Kansas, who said: “Curiosity is the passion that drives our lives.”

Six years later and Curiosity is still going strong. So far, it has travelled 18 kilometres, and climbed 327 metres. And Nasa isn’t coy about the fact that Curiosity is key to finding evidence for past or present life on Mars.

Gale Crater is the right environment to explore Mars’s history. Created by a meteorite impact 3.5 billion years ago, the basin is a rich territory of sediments – from water-borne fragments to wind-blown dust. The crater is testimony to two billion years of Martian evolution.

Bristling with experimental packages, Curiosity is looking at Mars’s climate and geology; environmental conditions for supporting microbes; and habitability studies for human exploration.

Drilling rocks, zapping them with X-rays, and probing them with microscopes, Curiosity’s scientists have come up with some remarkable conclusions. That there was once a large freshwater lake in the crater. That streams and rivers flowed. That methane in the atmosphere – an indicator of life (think farting cows) varies annually.

Nasa’s conclusion is that Curiosity has found evidence of “ancient lakes and rivers, a chemical energy source, and all the chemical ingredients necessary for life as we know it”.

Not surprisingly, Curiosity’s findings are prompting a flotilla of further probes to the red planet. Nasa’s InSight is on its way at the moment. Due to land in late November, the lander will explore Mars’s geological history.

On board is a microchip boasting the names of 2.4 million Earthlings bent on seeking immortality.

When Mars swings close to Earth again in 2020 (the planets come into register every two years), it can expect to be besieged. Probes from Europe, the United Arab Emirates, China, Japan and the US will converge on the red planet. Nasa’s Mars 2020 Rover mission even includes an add-on helicopter.

But most ambitious of all is Elon Musk’s 2024 plan to send a crewed mission to Mars. The hugely successful space pioneer, whose company SpaceX created the family of Falcon Rockets (including the incredibly powerful Falcon Heavy, launched in February), is proposing four flights in that year.

Will he be the first to get humans to Mars? Perhaps not quite that soon. But we’re certainly not betting against SpaceX.

What’s up?

The red planet is in line with the Sun and the Earth (and also the eclipsed Moon) on 27 July, and closest four days later when it’s a “mere” 57.6 million kilometres away. This is Mars’s nearest approach since 2003, when it was closer than it had been in 60,000 years.

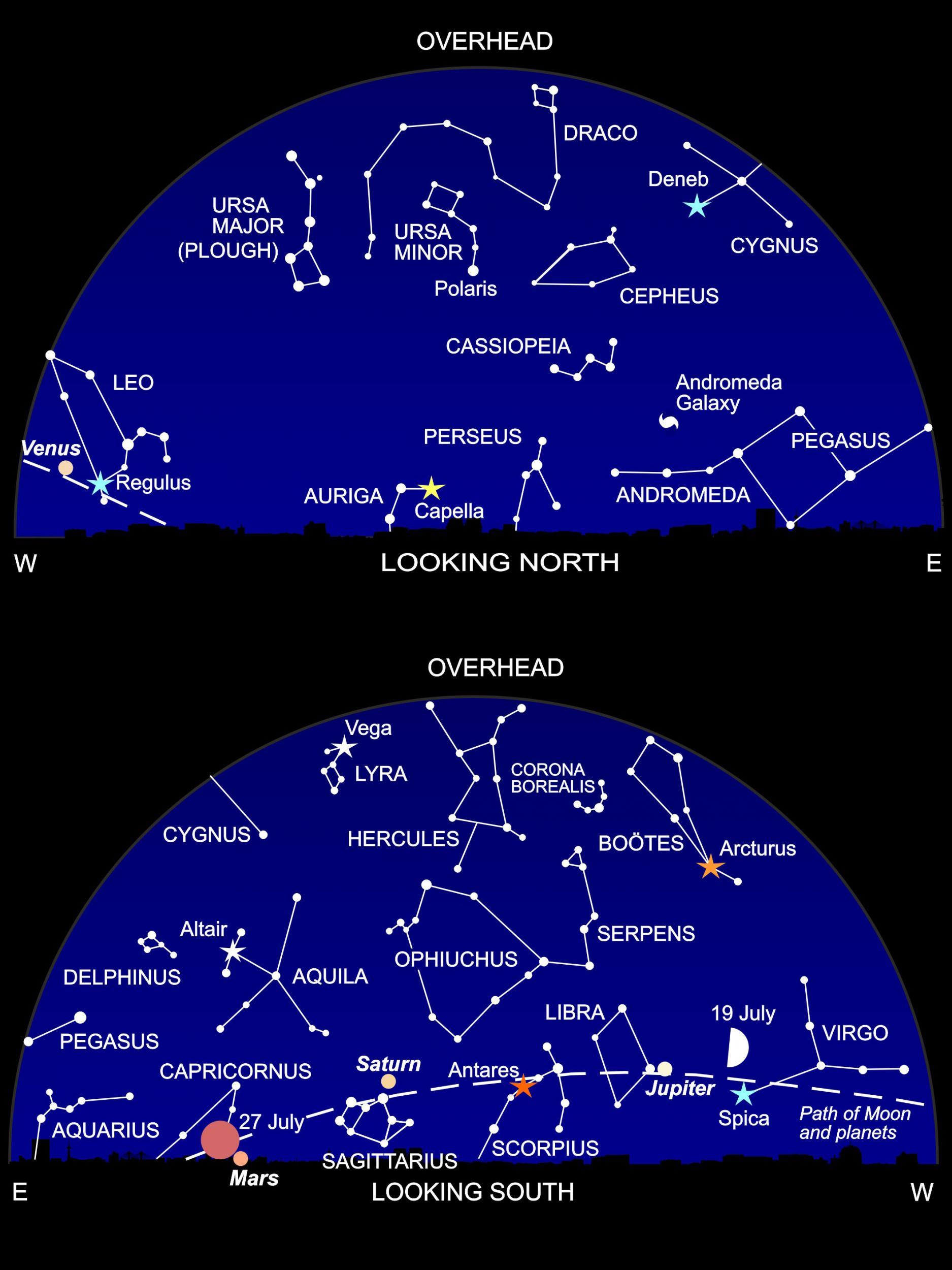

All month, Mars will be brilliant low in the southeast, in the faint constellation Capricornus. Grab a telescope if you can to see its red deserts, dark markings and white polar caps – though the view may be disappointing as a vast dust storm is currently engulfing the planet.

Mars is the jewel in a parade of planets and stars on view to the south this month. To its right, you’ll find ring world Saturn and then the red star Antares. Further to the right lies giant planet Jupiter, shining almost as brightly as Mars, and the bluish-white star Spica.

In the early evening – an hour or two after sunset – Venus is brilliant in the twilight glow to the west, next to another blue-white star, Regulus.

But back to the main event. On the evening of 27 July, look to the southeast around 9.45pm to see Mars rising above the horizon. Above it, you may spot a faint reddish ball.

That’s the Full Moon, but not as we usually know it. Our companion world is deep within the Earth’s shadow, so sunlight is not falling directly on it.

During a total lunar eclipse, though, the Earth’s atmosphere bends some of the Sun’s light into the shadow, so the Moon is faintly illuminated. These rays have been reddened because they’ve had to pass through our air – the same effect that makes the Sun appears red at sunset.

We can’t predict how bright or faint the eclipsed Moon will appear, as that depends on the Earth’s weather at the time. Heavy clouds cover block more sunlight, and the Moon appears darker.

By 10.13pm, the Moon will begin to slip out of the shadow. And by 11.19pm, it will be back to the undimmed brilliance of a normal Full Moon.

Diary

6 July, 8.51am: Moon at Last Quarter

6 July, 5.47pm: Earth at perihelion, closest to the Sun

9 July: Venus, very near Regulus

12 July: Mercury at greatest eastern elongation

13 July, 3.48am: New Moon; partial solar eclipse

14 July: Crescent Moon near Mercury

15 July: Crescent Moon between Venus and Regulus

19 July, 8.52pm: Moon at First Quarter, near Spica

20 July: Moon near Jupiter

22 July: Moon near Antares

24 July: Moon near Saturn

27 July, 9.21pm: Full Moon, total lunar eclipse

For the lowdown on all that’s up in the sky this year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book: Philip’s 2018 Stargazing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks