Ancient galaxies are casting long shadows across the universe, scientists say

Astronomers can now find early galaxy clusters by hunting their shadows

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Astronomers just hit on a new method for locating galactic protoclusters, ancient and elusive clumps of gas and galaxies in the early universe: They can look for the protoclusters’ shadows.

The new technique and results are described in a paper by researchers at the Carnegie Institute for Science that was published in Nature.

Protoclusters in the early universe are the forerunners of some of the most massive structures known, galaxy clusters, which can consist of thousands of galaxies bound together by their own gravity. So studying protoclusters in the early universe can give astronomers a better understanding of how the galaxy clusters they see closer to Earth evolved and formed.

Until recently, however, the only way astronomers could identify protoclusters was by scanning for areas in the early universe with a high density of galaxies. The sensitivity of such surveys depends on the dust content and star-formation activity in the galaxies.

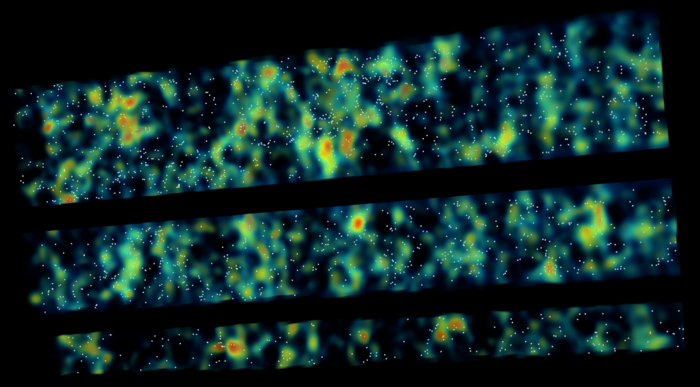

The new method detailed in the paper takes a different approach based on observations in ultraviolet light taken by the Magellan telescopes in Chile. The researchers found that the hydrogen clouds in the protocluster absorbed light passing through them and that this created a sort of shadow that could be seen on galaxies behind the protoclusters.

The finding is a good example of the value of deploying multiple techniques in astronomy, according to Carnegie astrophysicist and study co-author Gwen Rudie.

“One of the key lessons from this work is that as we map the distant universe, it’s important to bring together multiple perspectives,” she said in a statement. “Using just one technique can give a misleading picture.”

One surprising finding, according to the researchers, is that the identified protoclusters exhibit fewer galaxies than they would have expected. At least, galaxies that astronomers can see.

“We infer that half of their expected galaxy members are missing from our survey because they are unusually dim,” the researchers write in the paper. “We attribute this to an unexpectedly strong and early influence of the protocluster environment on the evolution of these galaxies that reduced their star formation or increased their dust content.”

Because these galaxies may appear dim in the ultraviolet wavelengths, the researchers note that future observations should look at multiple wavelengths in the protoclusters. Such a survey should find higher densities of galaxies in the protoclusters. If it doesn’t, it could force scientists to reconsider what they think they know about the evolution of the early cosmos.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments