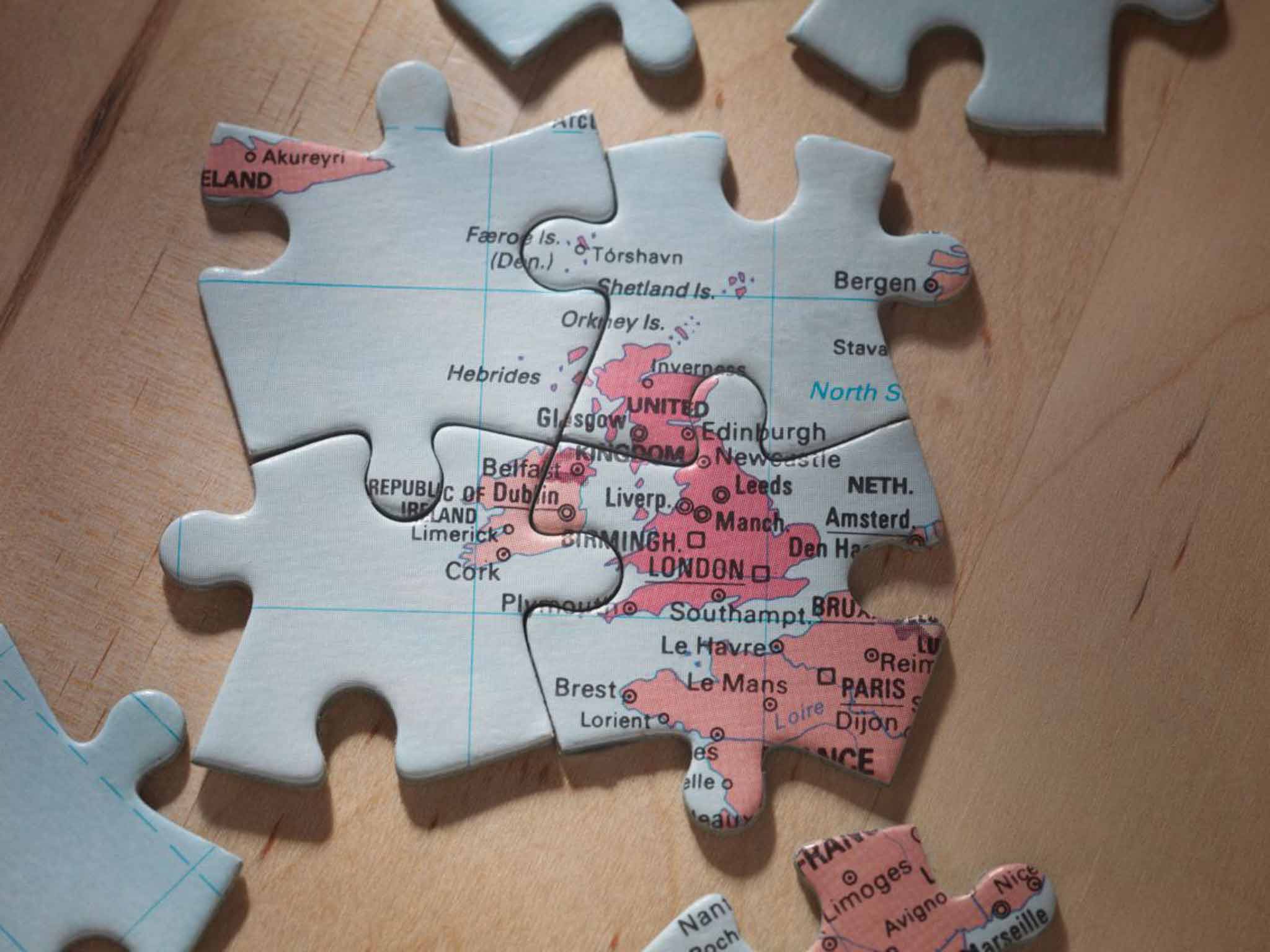

Scottish independence: Welcome to the nation formerly known as the UK

Whether Scotland votes Yes or No, we will all be forced to look afresh at our national identity. Hamish McRae - part Scottish, part English, raised in Ireland - dares to imagine a divided future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Whatever happens this week, the United Kingdom will be utterly different. The political construct that we call the UK may lose its 300-year identity altogether. That we will soon learn. But even if the UK nominally survives, it will become a much looser association – you might say a less united kingdom – carrying on the process of separation that began just over 100 years ago in May 1914 when Westminster finally passed the Government of Ireland Act, giving Ireland home rule. The First World War intervened, implementation was suspended, and the slither into the troubled subsequent relationship between our two countries continued for the rest of the century. In 1930, King George V remarked to his Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald: “What fools we were not to have accepted Gladstone’s Home Rule Bill.”

What fools indeed. Nearly all the public debate about the future relationship between Scotland and the rest of the UK has been about economics: the use of the pound, the responsibility for collective national debts, the rights to North Sea oil and gas revenues, the headquarters of the Scottish banks and so on. It has not been about the need to match political structures to identity – what kind of political relationship between the different people who share these islands is most likely to make as many people as possible feel happy and fulfilled. The nitty gritty of currency, North Sea revenues and so on is all fixable. You negotiate and do the deal. But you can’t negotiate about identity, so the deal has to be different. It is one of the paradoxes of our time that the more integrated the world economy has become, the greater the desire for local political control.

But many of us in these islands have multiple identities. For myself, it is being British – part Scottish, part English – but brought up mostly in Ireland, just south of Dublin, where I learnt my economics at Trinity College. Anyone who has lived in Ireland will think differently about England, seeing it with a certain detachment, respecting and being grateful for the opportunities it gives to people who seek to make their lives here, but also being troubled by its arrogance. That sense of detachment applies to people in Scotland, too – my spouse, Frances Cairncross, was brought up near Glasgow. Now we live mostly in London, but for more than 30 years have had a house in south-west Scotland, where we spend as much time as we possibly can. Whether you are in Dublin or Dumfries, Westminster seems a long way away. The difference is that in Dublin, you are in a society that makes its own decisions, good or bad, and takes responsibility for them, whereas in Dumfries, other people seem to make the decisions for you.

Or, at least, that is what it sometimes feels like. But this sense that Westminster is a long way away applies to much of England, too. One of the changes that will take place in the coming years, irrespective of the outcome of the referendum, is not just that decisions will become more local, but that the outcome of these different decisions will mean that different parts of England and Wales will be competing against each other more vigorously. To people who see competition in negative terms that might seem worrying and divisive. But it may result in more effective policies all round. Competition between American states is one of the drivers of the vibrancy of the nation.

All that would, or will, be for constitutional experts to tackle. My biggest concern is that in the event of a narrow No, the uncertainty about the future relationship would lead to more political and personal acrimony and start doing real economic damage to Scotland. We have caught a glimpse of that in the past few days as depositors have started to move money out of Scotland. In Canada, Quebec had suffered relative to Toronto from separatist pressures since the 1960s, right through two referendums, one only narrowly defeated, to today. In the long term there is no problem. Canada trades successfully with its neighbour the United States; Ireland trades successfully with the UK. But uncertainty does no good to anyone.

There is one further issue. It is how England will feel about itself. It will remain the dominant power of these islands, both in economic terms and population, for the foreseeable future. Within another 25 years, the UK may well have the largest population in Europe, and have the largest economy. Yet whatever the outcome next week the glue that holds the UK together becomes weaker. That suggests that these islands will become more important in economic terms, at least relative to Europe, but maybe find it harder to be assertive politically.

If the UK does break up, the choice will be whether England, plus presumably Wales and Northern Ireland, continue to try to be a mini-US, intervening in the great military and political issues of the world. Or whether it/they should try to be a big Switzerland, prosperous economically and more democratic in the sense that its regions will have a bigger say in policy, but increasingly unwilling to engage in global adventures. But even if it does not break up, I think we have to acknowledge that internal political tensions will increase and the more we become preoccupied with these, the less we are credible as an influence on global events.

Read more: A nation divided against itself

Who gets Jim Naughtie and will pillar boxes be blue?

The Quebec effect: Risks in Yes and No

Faced with slew of warnings, City takes a step back

Stepping back from a global role may be no bad thing. Politicians, certainly Westminster ones, like to strut about the world stage. The rest of us would just like them to be measured, cautious and competent. Insofar as the events in Scotland have been a wake-up call to all three major parties, then they probably needed it. The prize out there is to find a way of enabling all the people of these islands to get along better with each other. One of the triumphs of the past 20 years has been the transformation of the relationship between Ireland and England – I think England in particular rather than the UK as a whole. The visit of the Queen to Ireland in 2011 and the return visit of President Michael D Higgins to Britain this year have been lessons to all of us who sit between those two cultures. There was a sense of community when the President attended the celebration in the Royal Albert Hall in April that showed that English and Irish people, left to themselves, can get along wonderfully well.

That took a lot of work. I am afraid that some damage has been done to the relationship between Scotland and the rest of the UK during the past months, so there will be a lot of repair work ahead there, too. Those of us who sit between the cultures, and don’t in any case have a vote, should not, I suggest, tell people in Scotland what to do. But things have to be put back together, whether in the UK or outside it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments