The Secret History Of: Moka Express coffee maker

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

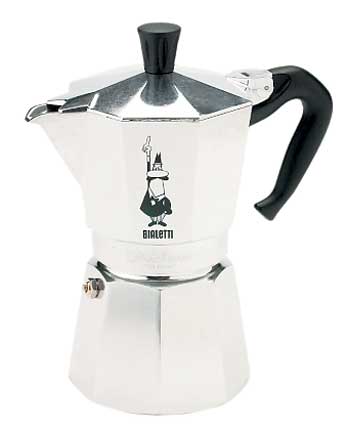

Your support makes all the difference.As it sits on the hob merrily bubbling and hissing away to make your coffee, who would have thought that this classic piece of Italian design was inspired by a washing machine?

The story of the stove-top espresso maker begins in 1918 when Alfonso Bialetti, returned home to Italy from France, where he had been working in the aluminium industry for 10 years, and set up a workshop making metal household goods.

Near his factory in Piedmont, Bialetti watched women washing their clothes in a sealed boiler with a small central pipe. The pipe drew the soapy water from the bottom of the boiler and spread it over the wet laundry. Bialetti decided to try and adapt this idea to make a coffee machine that would allow Italians to have real espresso in their homes.

Prior to that, coffee was generally drunk in public coffee houses, usually by men. Indeed when women started to drink coffee outside the home it was regarded as a sign of their move towards emancipation.

Domestic coffee machines allowed the hot water to drip gently over the coffee grounds to produce a weaker version of the real thing. But during this period various inventors had begun to experiment with steam in an attempt to emulate the strong and intense flavours of the espresso found in the public coffee houses.

Bialetti set to work using aluminium. Mussolini had imposed an embargo on stainless steel and as Italy had a rich supply of the aluminium ore bauxite and it became the national metal.

James Grierson, the owner of Galla Coffee, said: "He finally invented the Moka Express in 1933. Its distinctive shape was based on a silver coffee service that was popular in wealthy Italian homes at the time and hasn't changed since. He said that without requiring any ability whatsoever, one could enjoy an espresso in casa come al bar – in other words coffee as good as you could buy in the café."

At first, the Moka Express was sold at local markets and it was not until after the war, when Bialetti's son Renato joined, that sales took off after an advertising campaign using l'omino con i baffi ("the little man with the moustache"), a caricature loosely based on Alfonso Bialetti.

The design has hardly changed since and aluminium is still used.

"The residue of coffee from previous brews apparently taints the side of the Moka pot and adds flavour and depth," says Grierson. "That's why it is also recommended that you don't clean it too thoroughly."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments