The pandemic cracked a new generation of transgender people. Here’s why

When Covid-19 crashed its way into world history, ordinary people from Australia to Argentina were suddenly forced to confront feelings they’d been running from all their lives. Io Dodds unearths the little-known story of what the pandemic did to our genders

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Isis caught Covid-19 before most people had even heard the name. It was December 2019, and the young Indian medical student had been working in a respiratory medicine unit in Mangalore when a patient came in with a strange new virus.

This was one of the first cases in their state, and nobody yet knew how to combat the disease. So when Isis tested positive, they were put into total isolation for the next three months.

“I had to submit my temperature to the nurse about three times a day,” Isis tells The Independent. “I got meals delivered. I had to monitor my blood oxygen. I could read, play video games, and that’s it.”

With nothing else to do, Isis turned to the internet. They made a bunch of new online friends, many of whom were transgender or non-binary. Suddenly, they were forced to consider a question they’d been avoiding for their entire adult life: could they, too, be trans?

“That was when I realised that a lot of these people are exactly like me; they went through the same things that I did,” says Isis, who asked for their surname to be omitted because their family and colleagues don’t know they are non-binary. “Now my entire identity was in chaos. I didn’t know who I was anymore.”

Across the world, untold numbers of people were about to go through a similar process. They were doctors and teachers, students and software engineers, caregivers and the chronically ill; chefs, playwrights, archaeologists, and night shift grocery store managers. All were caught in a titanic collision between history and their own identity.

For Oliver, then a 35-year-old student in California, it came while he was stuck in Canada helping his sister look after her new baby, pushed into a maternal role that made his discomfort with womanhood inescapable and a forced sobriety that meant he could not numb it with alcohol.

For Lia Novaki, attending high school in rural Germany, it came while locked down at home with no lessons and no social life, and nothing but time and space to experiment with new clothes and new ways of seeing herself.

And for Sophia, a British emergency healthcare worker in her late twenties, it came while writing her will as she prepared to join the front line against a dangerous virus whose nature and fatality rates were not yet known.

“I’d long thought about transitioning, but there were things that put me off,” says Sophia, who uses both “she” and “they” as pronouns. “Suddenly there was a moment of clarity: actually none of this matters. I could die quite soon, and that’s it, and at that point it’s too late...

“[Being trans] was something I’d only really said out loud to a very small number of people in my life. But at this precise moment, nothing really mattered apart from whether or not I was going to survive this. And if not, then I didn’t want to be remembered as somebody I wasn’t.”

Trans people sometimes liken the moment where they truly realise they are trans to the first cracking of an egg as it hatches. Using that metaphor, the Covid-19 pandemic appears to have been a mass egg-cracking event without precedent in history.

The Independent heard from 205 trans and gender-non-conforming people who transitioned during the pandemic, and interviewed 16 directly. 195 of them submitted responses to an online survey created for this article, while the rest were contacted via other channels. Many, including Sophia, asked to be identified only by their first name or a pseudonym for fear of discrimination or exposure.

They lived in countries from Argentina to the Philippines, with ages ranging from their teenage years to their early sixties. 63 per cent of survey respondents said their egg cracked during the pandemic, 68 per cent said they started transitioning, and 6 per cent said they continued a transition they’d already begun.

Their experiences echoed those of trans celebrities such as the actor Elliott Page and the social media influencer Dylan Mulvaney, who attributed their awakening partly to Covid lockdowns.

Not a single person said the pandemic made them trans. Instead, they described how a global disaster made them confront feelings they’d been suppressing for years – just as it called our bluffs and wrecked our cosy fictions in every other part of society.

Together, they give new insight into a phenomenon that has attracted little popular attention and almost no academic research, yet has been widely discussed among trans people worldwide.

Call it the quarantrans era, or the trandemic, or even the Great Omelette. Whatever its name, it has deep implications not only for the lives of those it touched but for the future role of trans people in society.

This is the story of what happened to our genders since 2020, and why it matters.

1: ‘Like going to war’

Before Covid, Isis was simply too busy to think about their gender.

Raised as a boy in a conservative household, they’d known for a long time that something was “off”, but the “chaotic hell” of medical school left little time for self-examination. “I started applying to extra classes, putting in extra hours at clinic – anything to just avoid being alone with my thoughts,” they recall. “That is how I avoided this question for a long time.”

Almost everyone interviewed by The Independent described a similar stage of repression. Loue Tye, a 23-year-old teaching assistant at a high school in Norwich, England, had concluded they were probably non-binary eight years ago, but kept quiet out of fear they wouldn’t be accepted.

For Bex, a 32-year-old graduate student in genetics in New York City, the denial went deeper. Once, she had told her therapist that there was “some gender stuff going on” but that she didn’t want to talk about it. And then, for the next five years, they didn’t.

Never mind the recurring daydreams about having to explain to her lab that she’d mysteriously woken up as a girl. Or the idle fantasies of getting a chromosome test and finding out she was intersex. Or the thought that if she ever got testicular cancer, she’d just “get ‘em both off and go from there”. Somehow, none of it tripped her gender alarm.

Many people had stories like this. They knew in theory they could be trans, and had many thoughts and feelings that suggested they might be. But, whether due to outdated ideas about what “trans” meant or sheer magical thinking, they imagined it didn’t apply to them.

For cisgender (or non-trans) people, it can be hard to understand the impact of living with repressed gender dysphoria, which goes far beyond the well-worn concept of feeling of being “trapped in the wrong body”. It makes you say things like: “Before the pandemic, I barely had an experience of personhood, let alone gender” (Ellie, 22, in Melbourne in Australia). Or: “I was dead before, now I’m coming to life” (Erin, late thirties, in Florida).

Or, as Rey, 21, in Virginia puts it: “It feels like everything before the pandemic wasn’t even real.”

In the spring of 2020, things got extremely real. Sophia and their colleagues were briefed early on about the worst case scenario: mass infection, overloaded hospitals, and consequently mass death.

“We knew it was potentially going to be very big and very serious, based on what had happened in other countries,” says Sophia. “It kind of felt like going to war. It felt like: this is coming over the hill, and it might kill you. And you need to be ready for that. Are you ready?”

For Oliver, the answer was a resounding no. On March 11, the day the World Health Organisation declared Covid-19 a pandemic, he was at San Francisco International Airport on the phone to his sister in Canada, scrambling to figure out whether he should board his flight to see her.

“The trip was booked to be five or six days,” he recounts. “I knew it was gonna be a little longer, but I was like – ‘well, maybe it’ll be two or three weeks, and then this will all be over’.” He would not return to the US for nearly two years.

In Australia, then-26-year-old animation studio manager Jasmine Yang, whose egg had cracked in 2019, stuck her first estrogen patch onto her stomach in the break room of her deserted office in Sydney. A burst toilet had flooded her apartment, and strict new lockdown rules introduced on March 31 left her with no other refuge.

It was, she recalls, a moment of “sublime” strangeness. “Yeah, my apartment is flooded; yeah, the world is going through a pandemic; and yeah I’m sleeping on a s****y office couch. But right now, I have what I’ve been waiting 26 years to get, so life is pretty sweet.”

Each person had their own story of how Covid disrupted their life. Jack, a 20-year-old trans man, was attending an all-girls’ school in Ohio when classes switched to Zoom. “J”, a 23-year-old financial crimes investigator in Vermont, US, saw her new “dream job” travelling the world go up in smoke.

For many, the initial crisis gave way to an eerie calm. Cocooned indoors, cut off from their social networks, they were entering a vast social experiment with a simple if terrifying question: who are you when nobody’s watching?

2: Alone on an island

Overwhelmingly, the most common factor that influenced survey respondents’ transitions – chosen by 162 people, or 83 per cent – was “more time alone, prompting or forcing introspection”.

“My mind felt like my own space, for perhaps the first time ever,” says William Cuthbert, a 31-year-old freelance writer and journalist in Lincolnshire, UK. “Pre-Covid I’d always defined myself through other people and what they would find palatable or likeable. Having those social expectations forcibly stripped away pushed me to start digging inside myself for who I was without them.”

Femke, 32, had been trapped for years in a job she despised, scrambling to pay rent on her mouldy little apartment in a large English town. Only when Covid pushed her to quit, and move to a far cheaper house in rural Wales, did she have the emotional energy to start probing her gender issues.

In New York, Bex rode her bike around the deserted streets of lower Manhattan, seeing the National Guard troopers running drills and the refrigerated morgue trucks brought in to manage the flood of bodies. Yet the possibility of her own death only filled her with indifference, even relief. What’s more, she now realised she’d felt that way for years.

Searching for a reason to live, she gave in to a recurring thought and painted her nails. “It was a weirdly significant moment,” she says. “I looked down at my fingers, and I liked them. I’d never liked my fingers before. I wanted them to always look this way.”

This is often how it works when you’re not sure you’re trans. You try things out, and – perhaps to your surprise – they make you feel good. That gives you the confidence to keep trying things, even if you’re not ready to admit where they might lead (which Bex emphatically wasn’t).

Lockdown was the perfect cover for such delicate experiments. Never in living memory had so many people been seen so seldom by so few. It was as if some perverse genie had answered the collective prayers of nascent trans people for a safe space in which to grow, in a way none of them would have wanted.

53 per cent of respondents said “curtailment of face-to-face socialising” as a factor influencing their transition, and 63 per cent cited “not having to go out in public”. Among them was Leon, a 24-year-old French public sector worker who spent lockdown in a tiny Parisian flat with only his snaggletoothed grey cat Anakin for company.

“Quarantine was as close to the ‘if you’re alone on an island and have 100 per cent free and guaranteed successful medical care, what body would you like to have?’ thought experiment as I could have gotten,” he says. “There was literally no one to perceive me except my cat, who doesn’t care about gender.”

Lockdown also relieved many respondents from unwanted duties of gender performance. Several who were raised as women said that no longer having to be feminine at work helped them realise how much they always hated it.

Maeve, a 27-year-old escort and trans woman in Atlanta, US, had socially transitioned before the pandemic and "almost always" wore full make-up and feminine clothes in public. But she trails off and gets a faraway look in her eyes as she describes how much energy this took.

"It was f***ing exhausting," she concludes. "I'd do f***ing yoga to go grocery shopping, just so I was in the state I wanted to be in.”

This new freedom was aided by a mass migration to digital and online spaces, where identity is more plastic and trans community is easier to find. 103 respondents, or 51 per cent, cited "reliance on internet for social life", with four people specifically mentioning Nintendo’s March 2020 smash hit Animal Crossing: New Horizons.

3: ’I accepted that I might die’

Not everyone experienced lockdown as a relief. Like all the issues cited by respondents, its impact was complex and individual, affecting different people in opposite or paradoxical ways.

Some found themselves trapped at home with non-accepting or abusive family members, which delayed, sped up, or outright blocked their transition. “Coming out was impossible in a full conservative household,” says Mariana, a 36-year-old industrial designer in Colombia, who started hormone treatment in 2020 but had to stop when the pandemic devastated her finances.

“I couldn’t get out of my parents’ home, so I [couldn’t] come out of the closet, and I’m still closeted right now. Time passes, and it’s becoming harder to handle my dysphoria.”

Loss of income or work was another factor, cited by 12 per cent of respondents. Some said the pandemic had exacerbated personal problems such as depression, substance abuse, or eating disorders, which pushed them to resolve their gender issues. One person, 32-year-old Maddie in northern California, resolved to transition after having her entire town evacuated due to a wildfire.

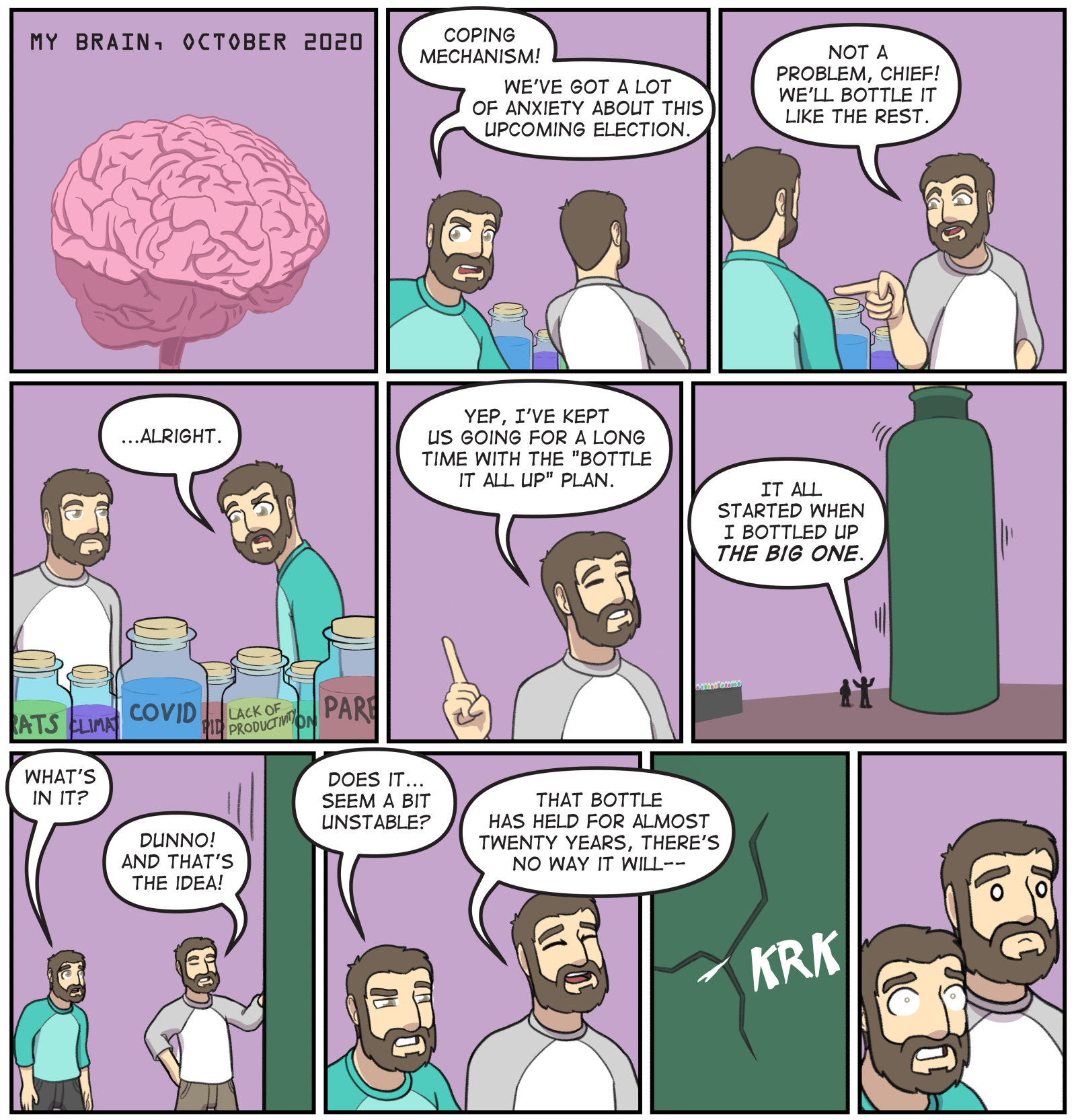

A widely-shared comic strip by Tennessee cartoonist Robin Brooks, 34, struck a nerve among pandemic transitioners, showing how the teeming anxieties of 2020 US election overwhelmed her coping mechanisms. “Something had to give, and it ended up being my denial,” Brooks says.

In Vancouver, Canadian border restrictions had turned Oliver’s expected week-long visit into months of full-time co-parenting with his sister. Outwardly, he looked like a cis a woman, causing both family and strangers to see him as a mother.

“I’ve always loved kids, but [constantly] being referred to as ‘motherly’ and ‘maternal’ in relation to a child felt almost too much to bear,” he says. “When I’d been viewed as feminine before, I’d been able to separate myself from it. But something about this situation just put it right in front of my face.”

His breaking point came in August 2020, when his brother died unexpectedly. Though the pandemic wasn’t to blame, it contributed to his sense that there was no more time to waste. He shaved his head, and got on testosterone.

In this Oliver was not alone. 54 respondents, or 28 per cent, cited “ever-present fear of death” as a factor influencing their transition. While lockdown may have cracked their eggs, it often took a brush with tragedy to make them take action.

“My family members all got Covid in November 2020 except for me, and my grandma almost died. I decided I was done not exploring the things I wanted to explore,” says Jason, a 31-year-old call centre trainer in North Carolina.

“I had been postponing transition for years until the ‘right’ moment, when I had graduated from college and become financially independent from my transphobic parents. The pandemic came and I realised I was going to die in the closet,” says René, a 23-year-old warehouse worker in Argentina.

“I’m immunocompromised, and I was hospitalised at the height of the pandemic, so I knew that if I caught Covid I could be screwed,” says one genderfluid 22-year-old in Oregon. “I accepted that I might die. Then I surprisingly didn’t, and I got a second chance to live life to the fullest.”

By the end of 2020, Covid-19 was better understood, and Sophia was less concerned that she would die. But in emergency departments and intensive care units, she’d seen patient after patient pass away with regrets and missed chances.

“They were saying goodbye to their families in video calls, and we were holding their hands as they died, because we were the only people who could,” says Sophia. “All of this really emphasised, for me, the fragility of life… and it solidified that there was no point in continuing to live a lie when it could all be snatched away so easily.”

4: Was there a ‘quarantrans’ boom?

It’s hard to know whether the pandemic actually increased egg-crackings overall. The population of knowingly trans people has been rising exponentially since long before the pandemic, thanks to the community’s success in sharing information, supporting questioning people, and advocating for greater acceptance.

Data from state-run gender clinics in England and Northern Ireland, made public via freedom of information requests by the British newspaper Metro, shows a massive drop in new adult patients in spring 2020 and then a sustained rise through the end of 2021. In the US, health insurance data showed that the number of children diagnosed with gender dysphoria nearly tripled between 2017 and 2021.

But Jeffrey Cohen, a psychology professor and trans health clinician at Columbia University in New York, cautions that such data is muddied by other factors such as access to healthcare.

“We haven’t seen any studies on that,” says Dr Rachel Levine, assistant health secretary to US president Joe Biden and the most senior openly trans government official in US history. While she finds the notion plausible, “as a physician and a public health professional” she wants harder evidence.

Ruth Pearce, a British sociologist who studies trans healthcare, similarly says that although she has observed the phenomenon anecdotally, she is “not aware of any formally published research” about it.

Trans support and advocacy organisations – including Gendered Intelligence in the UK, Quarks in Hong Kong, and Transgender Europe (TGEU) – expressed a mix of openness and scepticism about the “quarantrans” hypothesis, but all said there wasn’t much hard data to support it.

One group in Moldova, GenderDoc-M, did see inquiries from trans people “skyrocket”. But most were under 20 years old, suggesting the pandemic simply pushed that specific generation of trans people to crack all at once rather than gradually over the next few years.

Studies of already-out trans people, including by Quarks and TGEU, have found largely negative impacts from Covid-19, which cut off in-person support networks, trapped people in abusive homes, and blocked access to medical care.

Nevertheless, in online trans communities there has been an unmistakable surge in people attributing their self-discovery to the pandemic. Many have embraced the label “quarantrans”, reportedly coined by trans woman Joelle Tungus. Even if Covid had no effect on the overall numbers, it’s clear that it profoundly shaped the awakening of a whole generation.

“I have heard more than a couple of stories,” says Willow Fae, 36, a Twitch streamer in Alabama who prides herself on creating a welcoming space for questioning people. Throughout 2020 and 2021, roughly two people a week would approach her saying the pandemic had forced them to “face their demons” about gender.

Yang, who has a large following on Twitter, likewise says she was previously approached “two or three times a week” by questioning folk, many citing the pandemic.

Some survey respondents said they had seen a similar effect in their circles. “I have a lot of trans friends on Reddit, and all their eggs cracked in the pandemic,” says Novaki, whose local university LGBT+ group has now ballooned from three to five members to around 160.

“So I have this feeling that the pandemic really provided the push we trans people needed to realise what we are.”

5: Dominoes

In some ways, what happened to embryonic trans people during the pandemic is just one manifestation of what happened to everyone.

Millions quit their jobs in what became known as the “Great Resignation”. Psychologists and marriage counsellors say divorces have increased. Some realised they were gay or bisexual, while others learned that they had ADHD.

“People changed careers during Covid-19, or they moved across the country, or they broke up with their partner, because they realised – it’s a big watershed moment in history. May as well make a change while everyone else is making a change,” says Yang.

“LG”, on the US West Coast, puts it this way: “The pandemic had us collectively opting out of in-person work for many jobs. We opted out of student loans, we opted into relief programs. And so what if I opted out of gender?”

Yet if the Great Omelette did enlarge the trans community, that could give it more political power in future and increase the number of cis people who have trans people in their life.

Mainstream medical groups reject the idea that transness is a delusion spread via “social contagion”, as some anti-trans activists claim. But the knowledge and confidence necessary to begin transitioning certainly can spread, says Ruth Pearce, and each new trans person who comes out makes it easier for others.

Numerous respondents testified to the importance of trans role models, whether among their friends or on TikTok and YouTube. Some had already seen a second wave of comings-out in their circles, inspired by the first quarantrans cohort.

“This is obviously not ‘social contagion’,” says Bex, who is now finishing her PhD as an out and proud trans woman. “But seeing somebody walk down a path you didn’t think was possible lets you see that the path is there.” From off-camera, her fiancée shouts: “Dominoes!”

Life outside the eggshell hasn’t been easy. Some respondents, such as Isis, are still trying to figure out their gender, uncertain of the path ahead. Many emerged from lockdown into a more hostile world than they’d hoped.

Several said they had struggled to get transition care from overloaded medical systems, while others felt starved of in-person trans connections and overly dependent on social media. 68 respondents, or 35 per cent, said escalating anti-trans rhetoric had influenced their transition, sometimes causing them to hide their transness or stay in the closet.

“I've traded one huge catastrophe hanging over my head from the pandemic for the state of trans rights,” says Brooks. Nikha, a 21-year-old trans woman studying international relations in Georgia (the country, not the US state), laments that her nation will never tolerate a trans diplomat or academic, making all her hard work feel “pointless”.

When Oliver returned to the US in late 2021, strangers yelled at him on the bus, threw plastic bottles at his head, and called him a “f****t”. He took to drinking – a longstanding problem – which spiralled out of control until finally he checked into a trans-focused rehab clinic in Los Angeles.

For Sophia, these political shifts caused a lasting disenchantment from the country she was once ready to give her life for. “It sounds corny to say, but we had this big moment of national unity, almost, where I honestly felt this stuff couldn’t come back,” they say. “Probably for the first time in my life, I truly felt a little bit of patriotism.”

Instead, the British government has “turned around after Covid and spat in [her] face”. She is now planning to leave the UK.

Still, for all the hardship, most people – Oliver and Sophia included – said their lives are now far better for having transitioned. Some expressed uneasy gratitude for the pandemic, mixed with sorrow for what it stole.

“I’m living my life today with more joy than I could have imagined, but not all people have come out of the pandemic with positive experiences, or at all,” says LG. “I feel guilty that my life should be happier now after Covid started then before.”

In the end, joy is joy, and we take it where we can find it. Just ask Sylvia Denk, a 29-year-old trans woman from Buffalo, New York, whose egg cracked in 2020.

When she married her wife in autumn 2020, still presenting as a man, Covid prevented the big, traditional straight wedding they had planned. But that allowed them to invite friends and family to a “redo” ceremony in late 2021, with Denk in a wedding dress.

Months earlier, just before Denk started estrogen, the couple had decided to try for a baby in the “traditional way”. It worked, and their son was born in January 2022.

“Ultimately, the pandemic for me was full of second chances,” Denk concludes. “It gave me a chance to take a second look at gender and what it meant for me, processing feelings I’ve had my entire life. It gave me a chance to have a second wedding where I could be the real me. And it gave me the chance to have a son while being a mom.”

The Independent is a proud partner of Pride in London and supporter of Pride Month in the US. We are dedicated year-round to writing on issues facing LGBT+ communities across the globe. You can find our latest content here in the US and here in Europe.

This story is dedicated to Riven, who left us too soon. RIP.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments