The global economy is living dangerously – but don’t expect superpowers to follow the 2008 script

The IMF says the clouds are darkening. But why? The answers, says Ben Chu, are trade wars, rising US interest rates and Brexit

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Twelve months ago the global economic outlook was encouraging, strong even: 2017 had seen the best year of international GDP growth since the aftermath of the financial crisis and 2018 seemed to offer even better. “The global cyclical upswing that began midway through 2016 continues to gather strength,” reported the head of economics at the International Monetary Fund, Maury Obstfeld.

Stock markets were booming. Business confidence was high. Consumer sentiment was robust. It looked like the world was finally shaking off the painful memory of the global financial crisis a decade ago. Now things are looking far less rosy.

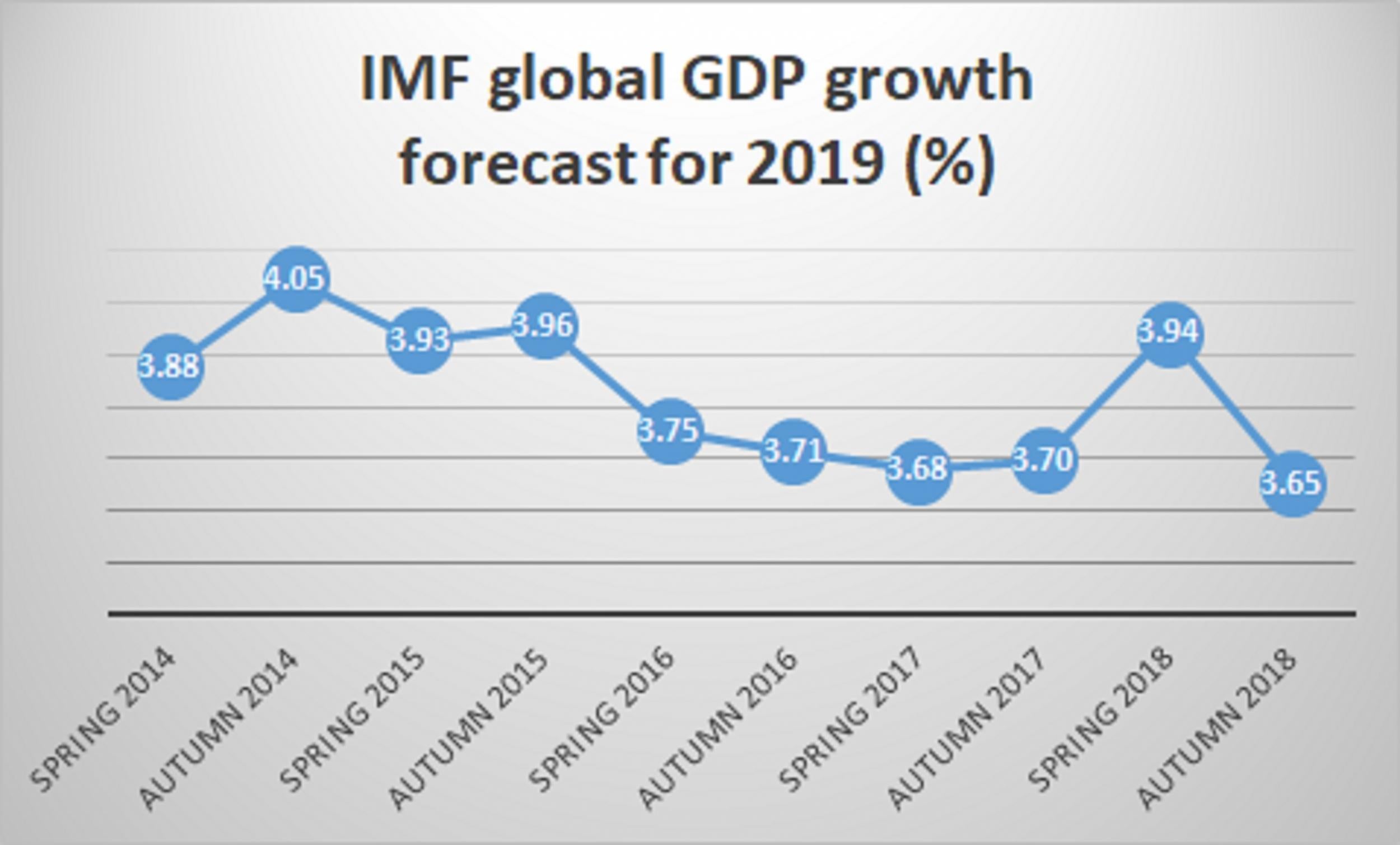

True, on the surface not much has changed. The International Monetary Fund expects global growth in 2019 to come in at 3.7 per cent, the same as expected for 2018 and 2017. Yet this is a downgrade from the 3.9 per cent the fund was expecting eight months ago – and the consensus among private sector economists is that it will be only 3.6 per cent.

US growth is expected to slow quite markedly from 2.9 per cent in 2018 to 2.5 per cent in 2019, as the stimulus from Donald Trump’s unfunded tax cuts wears off. Expansion projections in the US, Germany and France have also been shaved down. There have also been downgrades for China, India, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa. Closer to the ground things look even uglier.

The German, Italian and Japanese economies unexpectedly contracted in the third quarter of 2018, in the most recent official GDP data from those countries. The German contraction – mainly due to factory closures in its automotive sector – was the first since 2015. Chinese growth in the third quarter – 6.5 per cent year-on-year – was the lowest for a decade. Survey indicators of activity by sector have slumped in most countries since the summer.

And stock markets have also wilted dramatically over the past few months. The MSCI World Index of shares has slid 15 per cent since September and ended the year down more than a tenth from where it started. Emerging market stock exchanges are also in a bear market, meaning they have fallen more than a fifth since their recent highs.

“The expansion may have peaked,” warns the IMF. “We have had a good stretch of solid growth by historical standards, but now we are facing a period where significant risks are materialising and darker clouds are looming,” says the fund’s managing director Christine Lagarde.

What next for global growth?

So what explains those darkening clouds? To put it concisely the answers seem to be: trade wars, rising US interest rates and Brexit. Donald Trump’s trade aggression towards China – his tariffs on $200bn of imports and threats of more – appear to be, finally, hitting the real economy, undermining sentiment among firms, harming investment.

New export orders for manufacturers have fallen into contraction territory in Germany and China. Container port traffic growth has also decelerated sharply.

Despite the rhetoric from Washington and Beijing, the “deal” between the two nations at the G20 in Buenos Aires in December is plainly a temporary ceasefire rather than an armistice.

The IMF calculates that Trump’s threatened car import tariffs on all countries except Canada and Mexico could hit global GDP in the immediate term by 0.75 per cent. The Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development is just as worried. It estimates that tariff hostilities could knock up to 2 per cent off world trade by 2021.

Then there’s monetary policy. The president’s domestic tax cuts have clearly boosted short-term GDP growth in the world’s largest economy but they have also prompted the US central bank to raise interest rates to head off what it sees as the threat of unstable inflation. The federal funds rate now stands at 2.5 per cent and at least two more hikes are priced in by markets for 2019.

In the past an “inversion” of the US borrowing yield curve, where 10-year rates dip below two-year rates, has presaged an American recession. Weak rises in long yields relative to spiking short-term yields this year means that an inversion seems to be getting steadily closer.

Debt, falling growth and rising rates expose sovereigns to the risk of shocks

“The gradual increase in interest rates by the US Federal Reserve has been enough to raise the value of the dollar, undermine confidence in emerging markets and tighten global monetary conditions,” says Gavyn Davies of Fulcrum Asset Management. “This process may or may not end in recession, but it is certainly already causing ‘recovery fatigue’ in most parts of the world economy.”

Tightening of the US monetary system tends to hit emerging markets. “There has been an abrupt ‘stop’ of capital flows to emerging markets over recent months, which has created painful consequences for [those] with large external deficits,” says Adam Slater of Oxford Economics.

The spectre of monetary tightening and its impact also haunts Europe. The eurozone economy expanded by just 0.2 per cent in the third quarter of 2018, its slowest quarterly pace in more than four years. Memories of 2017, when the single currency grew by 2.4 per cent, its fastest rate in a decade, are long gone. The IMF projects growth of only 1.9 per cent in 2019 for the eurozone.

That may be overoptimistic. In Italy growth is expected to slow from 1.2 per cent to 1 per cent next year, despite the avoidance of sanctions from the European Commission over its budget plans. The populists in Rome have backed down on borrowing for now – but the fire could yet reignite in the new year. And the European Central Bank has signalled that this slowdown and political strife will not prompt it to re-start its €2.6 trillion monetary stimulus programme, which ended this month.

Finally, there is Brexit. The IMF has pencilled in non-catastrophic growth for the UK economy next year of 1.5 per cent, up from 1.4 per cent in 2017. But this is, of course, was predicated on the assumption of a smooth exit from the EU next March, or rather entry into a 21-month single market and customs union transition where nothing really changes.

The Bank of England says that if Brexit is, on the contrary, economically “disruptive” and we get no deal with the EU the UK economy could contract by 3 per cent. And in a worst-case scenario of a “disorderly” no-deal Brexit it could contract by 8 per cent. That would make the economic collapse bigger than that in the global financial crisis in 2008.

That’s a relatively low probability downside risk rather than a baseline of course. But on the tenth anniversary of the financial meltdown it’s as well to remember that sometimes perceived low probability downside risks materialise – and they do so with no mercy. The other great lesson from the financial crisis in 2008 is that risks can materialise from unexpected quarters. Perhaps a political shock could come from another refugee surge from the Middle East or North Africa. Or maybe it could come from a devastating cyberattack on business or government.

In the November Budget the Office for Budget Responsibility put the odds of another UK recession over the next five years, on a historical basis, at 50 per cent. If the wider world economy does stumble into contraction over the next 12 months it’s also important to bear in mind that government debt burdens are significantly higher than they were a decade ago and that interest rates in the advanced world could not fall as far as they did then. This may limit the room for stabilising monetary and fiscal measures from governments.

“High debt, falling growth and rising rates expose sovereigns to the risk of shocks that undermine debt affordability and sustainability,” cautions the credit rating agency Moody’s.

And as Gordon Brown observed this year, in this era of trade wars and fraying multilateralism, we may not have the worldwide cooperation necessary to get us out of another global crisis like 2008.

For the world – and especially Britain – 2019 looks set to be a year of living dangerously.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments