John Artis: Campaigner wrongfully convicted alongside ‘Hurricane’ Carter

Although he was never mentioned in Bob Dylan’s famous protest song, Artis had to fight the system to clear his name of murder

Imprisoned for a triple murder he insisted he never committed, prizefighter Rubin “Hurricane” Carter became a cause celebre, immortalised in a Bob Dylan protest anthem and portrayed by Denzel Washington in a 1999 film.

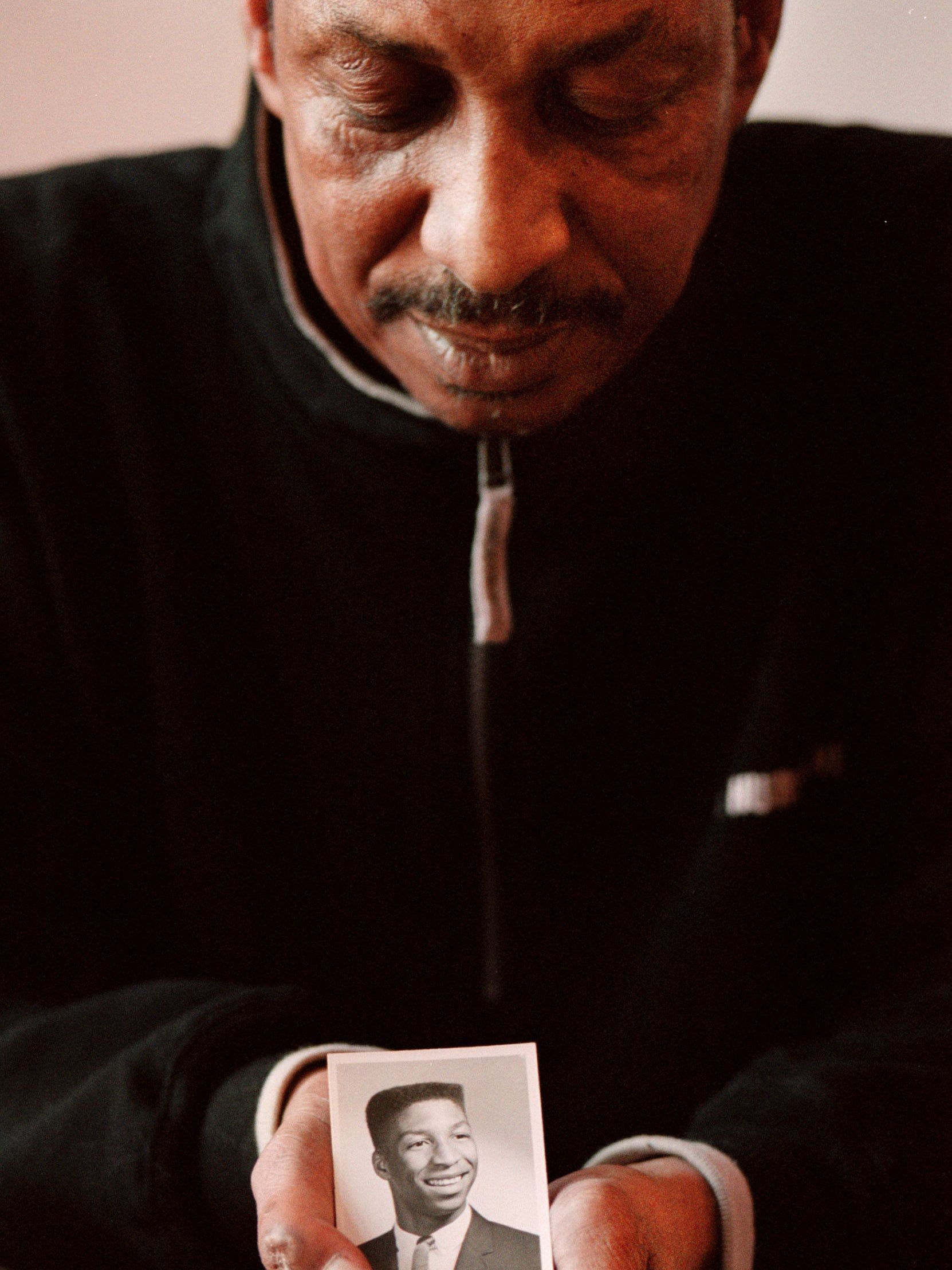

But the song, “Hurricane”, never mentioned his co-defendant, who scarcely appeared in the movie of the same name. Both men endured two trials, multiple appeals and years in prison before their convictions were overturned. “I was always the guy in the background,” John Artis once said, “the other guy in the case that no one knew or cared about.”

Artis, who has died aged 75, later counselled troubled youth and spoke on behalf of the wrongfully convicted, condemning racism and official misconduct in the criminal justice system.

Over the decades, he and Carter were variously described as cold-blooded killers and as innocent victims of a flawed and sometimes racially biased justice system. Both men were Black, and their three alleged victims were White, gunned down at the Lafayette Bar and Grill in Paterson, New Jersey, one night in 1966. The two men were pulled over by police a few minutes after the murders because they were driving a white Dodge Polara that apparently resembled the getaway car of the shooters.

“The case inspired a generation of lawyers working to free innocent people,” Justin Brooks, director and co-founder of the California Innocence Project, said. He added that Artis’s and Carter’s “suffering led to the freedom of so many other people who found themselves in the same situation. I’m very sad that they are both now gone, but their legacies live on in all of our work.”

Artis and Carter were casual acquaintances at the time of the killings. Carter, 29, was a leading middleweight boxer; Artis, 19, had recently graduated from Paterson Central High, where he starred on the track team and played football and basketball. With the death of his mother, he decided to postpone university, and was working as a truck driver when he spotted Carter at a nightclub and asked for a lift home. Carter handed him the keys, and they were soon stopped by police.

From the beginning, the two men insisted they were not the killers. They passed lie-detector tests, provided alibis and were released after a witness said neither man was involved in the shootings. But nearly four months later, they were arrested following testimony from two men who had been committing a burglary nearby and who claimed to have seen Artis and Carter at the Lafayette.

An all-White jury found them guilty in 1967, with Carter sentenced to two consecutive life sentences and Artis receiving one life term. “I told myself, ‘It’s just 14 football seasons, 14 basketball seasons, and I can make it,’” Artis later told The Washington Post, referring to the time he had left before he was eligible for parole.

He played football, started a prison track team that raced for cigarettes and taught other incarcerated people to read and write.

During a riot at Rahway State Prison in 1971, he rescued four guards who were being held hostage, demanding that they be released to him. He led them to safety and was later transferred to a minimum-security prison, enabling him to take business classes at Glassboro State College, now Rowan University.

In 1974, the two burglars recanted their earlier testimony, saying they had been pressured by detectives to incriminate Artis and Carter. Bob Dylan recorded “Hurricane” the next year, helping to draw national attention to the case – “Here comes the story of the Hurricane / The man the authorities came to blame / For somethin' that he never done” – and in 1976 the New Jersey Supreme Court overturned their convictions, ruling that the prosecution had withheld evidence.

Artis and Carter were free for about nine months before being convicted in a second trial. One of the burglars reversed his recantation, implicating the defendants, and the prosecution argued that the killings were racially motivated retaliation for the murder of a Black bar owner by a White man that same night.

After nearly 15 years in prison, Artis was released on parole in 1981. Four years later, when the case reached the federal courts on appeal, US District Judge H Lee Sarokin overturned both men’s convictions, prompting Carter’s release. Sarokin ruled that the prosecution had withheld evidence and violated the defendants' constitutional rights, developing a line of argument that was based on “an appeal to racism rather than reason, concealment rather than disclosure”.

“It has taken 20 years for the truth to come out,” Artis said at the time, “and for someone to show all the red herrings that the prosecution used to convict us.”

By then, however, Artis was facing health problems in addition to legal issues. During his second stint in prison he was diagnosed with Buerger’s disease, a rare circulatory disorder that led to the amputation of some of his fingers and toes. He said he began using cocaine after reading in a medical journal that the drug helped some people with circulatory diseases, and pleaded guilty in 1987 to conspiracy to distribute $50 worth of cocaine and to receiving a stolen handgun.

Rather than granting him probation as a first-time offender, a judge sentenced him to six years in prison, citing his murder conviction even though it had been overturned. A judge ordered him released in 1988, after the US Supreme Court denied a request to review the triple-murder case. New Jersey prosecutors declined to bring a new trial.

No one else was arrested for the killings.

Artis said he calculated his prison time in months, weeks, days, hours, minutes and seconds – 4.7 million – and considered suing the state of New Jersey for his wrongful conviction. But “they couldn't pay me what I want”, he told The Post in 2000. “Would $2m or $3m make it right? I want $200bn for every year. I want $200bn for every day. I won't ask them to determine what they think my life is worth. I've seen what they think it's worth – nothing.”

John Arnold Artis was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, on 15 October 1946. His mother was a domestic worker, and his father was a labourer who became a chemical engineer for Merck. Not wanting to raise their children in a segregated city, they moved to Paterson when Artis was eight. He became a Boy Scout and choirboy and maintained an interest in music throughout his life, teaching himself to drum during his second stint in prison.

While behind bars he also married Dolly Williams, a social worker, in 1980. They later divorced. In addition to his sister, survivors include a stepsister.

After his release, Artis counselled young offenders at the Norfolk Juvenile Detention Centre. “This work is like a calling for him,” his boss Carlton Baker told The Post. “He’s on a mission to keep as many kids as he can out of trouble.”

Artis also remained close with Carter, working with him at wrongful conviction groups including Innocence International and Innocence Canada. When Carter became ill with prostate cancer, Artis moved to Toronto to care for him, remaining there until Carter’s death in 2014 at age 76.

In interviews, Carter often called Artis “my hero”, saying that Artis had rebuffed New Jersey officials who offered him his freedom in exchange for incriminating testimony. As Artis told it, he was approached in 1975 by two aides to governor Brendan Byrne, who told him he would “be home in two weeks” if he implicated Carter.

“I won’t sign anything that’s untrue,” Artis recalled saying, “and that’s a lie.”

John Artis, campaigner, born 15 October 1946, died 7 November

© The Washington Post