'Worst. Eclipse. Ever': How I spent a year hoping for an other-worldly experience

For Ryan Milligan, even a trip to the Faroes did not guarantee a total eclipse of the heart

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I started planning for this solar eclipse almost a year ago. Even then I knew I might be cutting it fine. Having travelled all over the planet to see four total eclipses to date, I was going to make sure I didn’t miss one in my own back yard, so to speak.

Unless you’ve witnessed a total solar eclipse it’s hard to convey just why so many people travel halfway around the world to experience a celestial alignment that lasts mere minutes.

The visual and emotional spectacle of seeing the Moon cover up the last few pieces of the Sun’s disc, before plunging your surroundings into darkness, save for the ethereal overhead glow of the Sun’s ghostly outer atmosphere – the corona – is without question the most awe-inspiring sight in nature.

Even with 93 per cent of the Sun being occulted from my hometown of Belfast, the closest place to experience the totality of yesterday’s eclipse was going to be the Faroe Islands, 500 miles north of Scotland. With a population of only 48,000 this would swell by over 8,000 on the days around the big event.

When I arrived there was a palpable sense of excitement amongst the locals, with just a hint of trepidation: weather in the north Atlantic is notoriously unpredictable, and with hours to go it wasn’t very encouraging.

Our tour group consisted of novices and veterans alike; young and old, from every corner of the globe. The first guy I chatted to at the check-in line at Gatwick was from just outside Washington DC, near Nasa’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, where I have spent half of the past decade conducting my own research into the solar corona.

Scientifically, solar eclipses have heralded many major discoveries about the Sun over the past few centuries, but in doing so have also raised more questions; ones that we are still struggling to answer.

Today, we have uninterrupted views of the corona from spacecraft in orbit around the earth that we use to help understand the nature of the Sun and its activity, but still none compare to that which nature provides.

Our choice of location for viewing the main event was chosen largely by eclipse expert Dr Kate Russo, who had been on the islands for several weeks working alongside local meteorologists, astronomers, and community leaders to secure the best spot possible. So thorough was their research that the BBC Stargazing Live crew opted to join us and the residents of the fishing village of Eidi (pronounced ah-ya) to film the event. The drive from the capital, Tórshavn, took an hour with the majority of it spent beneath thick rain clouds. Upon arrival in Eidi, little had changed except for some promising patches of blue sky on the horizon.

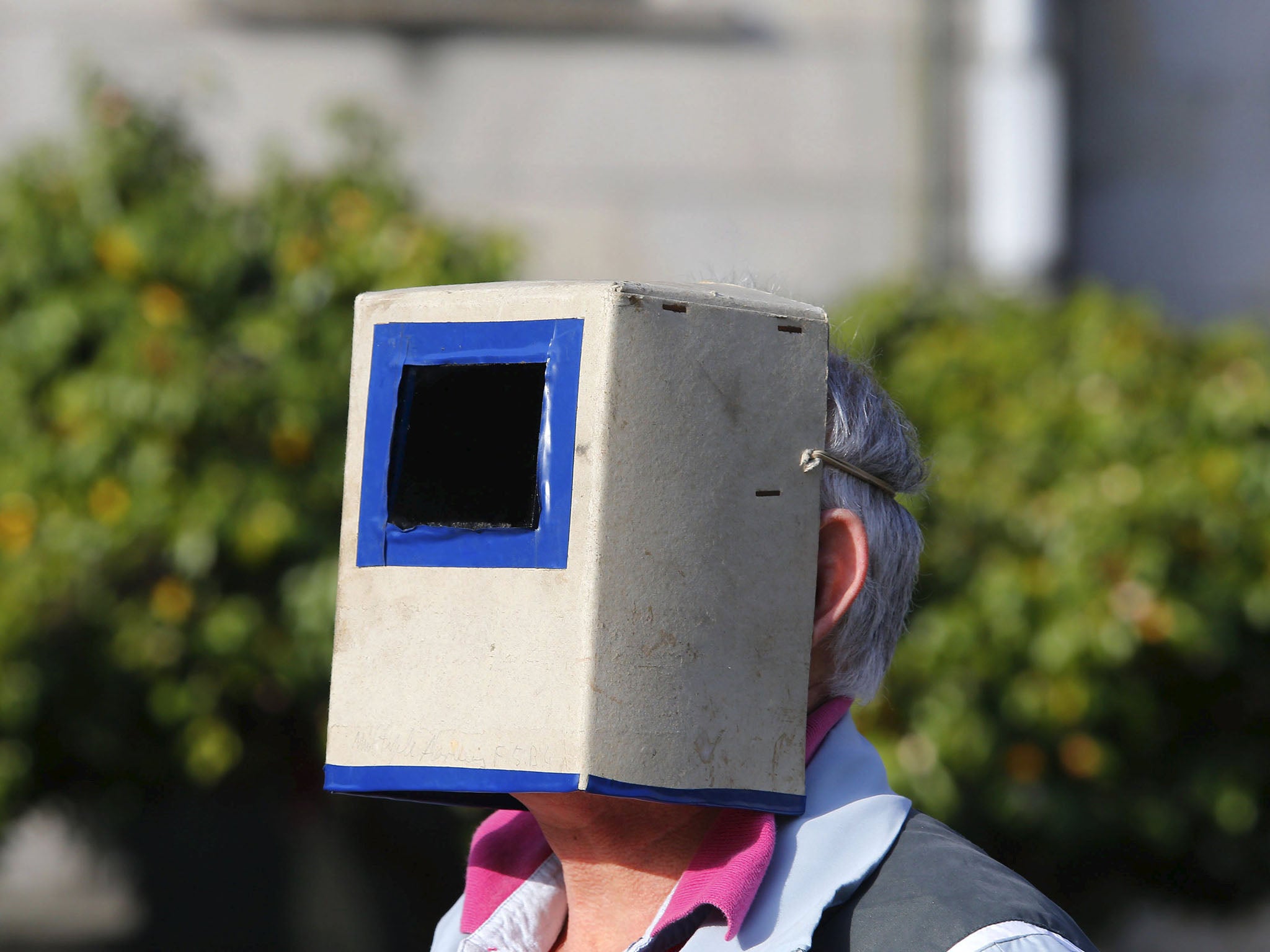

With two hours until totality the mood was cautiously optimistic that one of these patches would coincide with the position of the Sun at just the right time. Both visitors and locals gathered outside the village primary school, closed for the day in celebration, and began setting up various cameras and telescopes.

Despite the weather, spirits were un-dampened, but as time went on it became increasingly obvious that the outlook was not promising. The possibility of jumping in our cars and relocating to a clearer location seemed equally futile. Ultimately, we accepted the inevitable and resigned to experiencing the impending 2 minutes and 20 seconds of darkness without witnessing totality itself.

And darkness did indeed fall. All around us the light levels dropped dramatically.

This was it.

We were standing in the shadow of the Moon. The cloud-cover adding to the drama. The darkness felt heavier and more ominous, creating an altogether eerie atmosphere, certainly compared to my previous eclipse experiences which had all been under clear skies.

It was hard not to feel a little deflated on this occasion. Upon returning to Tórshavn I learned that many of the locals did get to witness totality, in some cases for only a few brief seconds, but perhaps this will have been enough to justify the preparation and build up that this incredible island nation have put into accommodating the influx of ‘astrotourists’.

And maybe, just a few will have developed a taste for that experience.

With the next total solar eclipse less than a year away, passing over much of Indonesia in 2016, and the one after that being perhaps the most accessible of a generation as it passes over the entire continental United States in August 2017, the opportunity exists for anyone with a sense of wonder to experience first-hand the profound beauty of our nearest star.

Dr Ryan Milligan is a Nasa solar physicist based at Queen’s University Belfast

Cloudy and unclear: mixed viewings

Londoners were left underwhelmed as thick cloud ruined the spectacle. One disappointed observer summed it up on Twitter: “Worst. Eclipse. Ever.”

Viewed (or not) from London, 85 per cent of the Sun was obscured by the Moon at the peak of the eclipse.

Wales proved one of the best places to experience the event, with the Sun clearly visible before being reduced to a thin silvery crescent.

Other good vantage points included parts of the West Country and the Midlands.

In south Gloucestershire, amateur astronomer Ralph Wilkins described an “eerie” feeling as a chilly gloom descended.

The proportion of the Sun shielded by the Moon increased toward the north, with 93 per cent covered in Edinburgh and 97 per cent in Lerwick in the Shetland Isles.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments