A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: White feather for winner of Victoria Cross

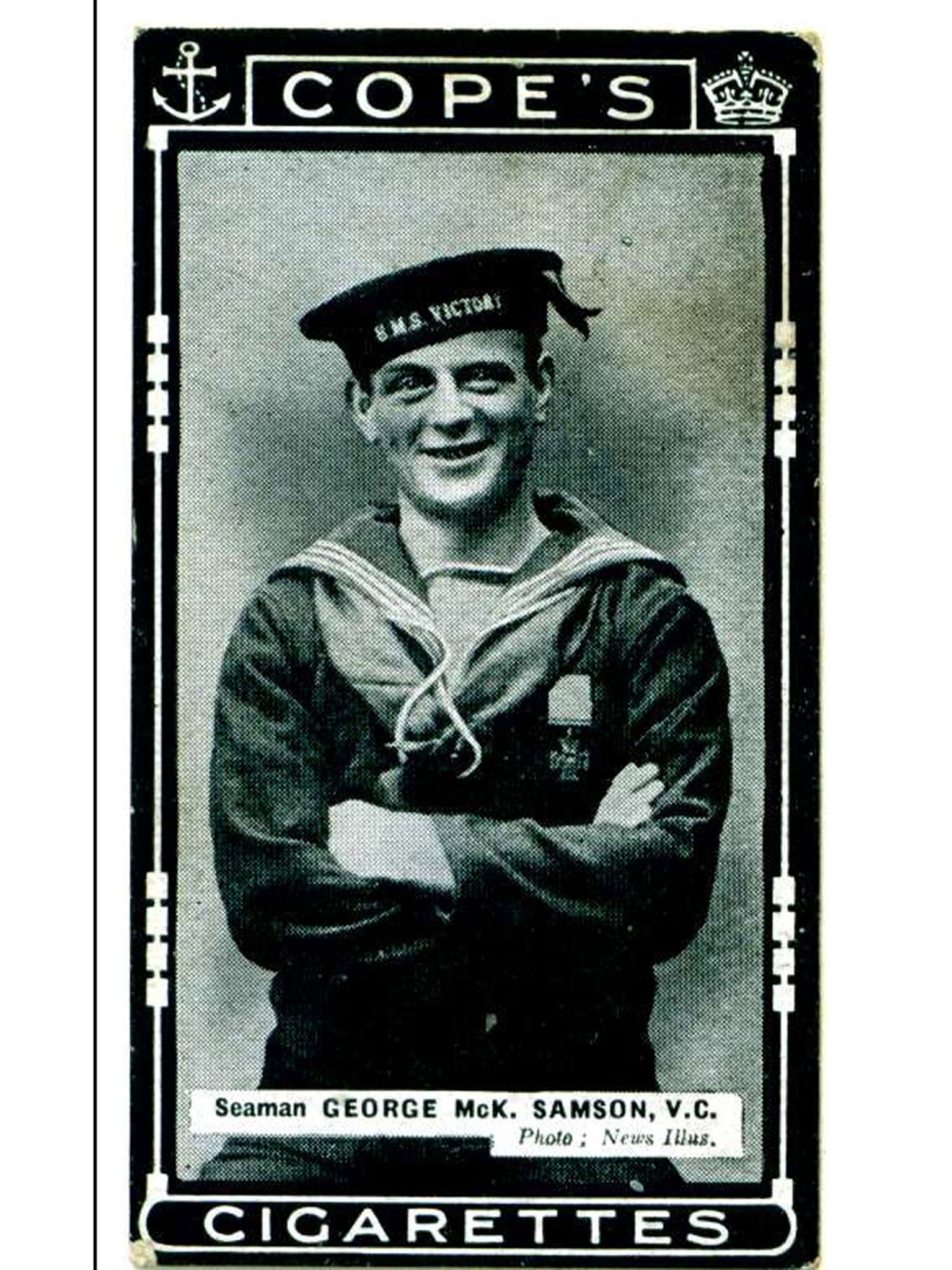

Carnoustie, 12 October 1915: George Samson is humiliated as a coward. A few female patriots liked to humiliate young men they saw on the streets out of uniform. Even a war hero, in his home town, was not exempt

In October 1915, a woman approached George Samson in his native Carnoustie and handed him a white feather. He became one of thousands of men out of uniform who were humiliated on the streets of First World War Britain by being publicly given the symbol of cowardice.

In the case of Petty Officer Samson, it was a slight that could not have been more ill deserved. Within hours of receiving the feather from a stranger, he was the guest of honour at a formal reception in Carnoustie where he was presented with different tokens of esteem – a smoker’s cabinet and a rose bowl.

The occasion was for the Angus town to celebrate the award to one of its own of the Victoria Cross, for astonishing bravery barely six months earlier during the bloodbath of the Allied landings on Turkey’s Gallipoli peninsula.

While helping soldiers ashore from his ship, HMS River Clyde, the 26-year-old seaman attended to a tide of wounded for an entire day, hauling them to safety despite being wounded himself in a constant hail of machine-gun fire. It was only when he was cut down by as many as 19 bullets that the Scot, who had led an extraordinary existence working as a cowboy in South America and a train driver in Turkey, was finally pulled from the battlefield and treated for injuries he was not expected to survive.

The ship’s surgeon, Dr P Burrowes Kelly, commented: “Whether he lived or died, I knew he won the VC.”

The symbolic slandering of a war hero was an extreme, though by no means unheard of, example of a practice which had first emerged as early as 1914 thanks to the efforts of Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, a retired naval officer based in Folkestone, Kent, who founded the Order of the White Feather.

Supported by a number of prominent female writers and leaders of the Suffragette movement, the Order encouraged young women to hand out white feathers to young men spotted on the streets out of military uniform.

At the outset of the war, Britain relied on volunteers to fill the trenches and recruiters were not afraid to harness the power of shame and embarrassment to fill their quotas of men to ship to the killing fields of France and Belgium.

One army recruiting poster, addressed “To the young women of London”, baldly stated: “Is your ‘Best Boy’ wearing Khaki? If not don’t YOU THINK he should be? If your young man neglects his duty to his King and Country, the time may come when he will NEGLECT YOU!”

The white feather movement unabashedly capitalised on such sentiment and within weeks young men were being confronted by women bearing their symbols of cowardice.The effect was often powerful and immediate.

James Lovegrove was only 16 when he was confronted by a group of women on his way to work. He wrote: “They started shouting and yelling at me, calling me all sorts of names for not being a soldier! Do you know what they did? They stuck a white feather in my coat, meaning I was a coward. Oh, I did feel dreadful, so ashamed. I went to the recruiting office.”

Despite initially being told to go away because he was under age, the recruiting sergeant eventually took pity on him and falsified his measurements. Lovegrove added: “All lies of course – but I was in.”

Petty Officer Samson was by no means the only serviceman to be wrongly singled out for a feather, which were also handed out by supporters of Christabel Pankhurst, the daughter of Suffragette leader, Emmeline.

One, Pte Harold Carter, told how he was handed one while standing outside a music hall in civilian clothes when on leave from the trenches and was then abused by a Royal Navy officer who told him a man out of uniform was “nothing more than a worm”.

Carter wrote: “He made me feel about as big as a worm. I just sat there on my own while people looked at me. I should like to have jumped up and told them I’d just come out of the trenches at Ypres, but I couldn’t. I came out disgusted and went home.”

The distribution of feathers, which was also accompanied by anonymous letters sent to the homes of targeted men, drew a political backlash. Calls were made to the Home Secretary, Reginald McKenna, to arrest those responsible.

He declined but the authorities came up with a number of badges and arm bands to be worn by men in exempted professions or who were awaiting their call-up papers after conscription was introduced in 1916 to show they were serving “King and Country”.

Others, however, dealt with the attempt at humiliation with humour. A prominent pacifist, Fenner Brockway, claimed he had received enough feathers to make a fan. The prize for chutzpah while under fire from the Order of the White Feather, however, goes to Pte Norman Demuth, of the London Regiment, who was confronted by a female detractor while on a bus. According to an account of the incident, he took the feather and used it to clean his pipe before returning it to the woman and saying: “Thanks very much. We don’t get pipe cleaners very often in the trenches.”

Tomorrow: A British woman in Serbia’s army

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks