A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Poet Giuseppe Ungaretti finds his voice amidst the horror of the ‘white war’

Italians endured years of bloody, futile fighting in the Alps. But a literary giant arose from the carnage. Peter Popham on the awakening of the artistically-inclined 27-year-old

On the morning of 23 December 1915, in the aftermath of another appalling and pointless battle on the Italian front, a tall, shambling, sleepy-eyed soldier took a pencil and scrawled these lines:

One whole night/thrown down nearby/a slaughtered/comrade his mouth/rigid and upturned/to the full moon/his swelling hands/delving into/my silence/I wrote/letters full of love/ Never have I held/so hard to life.

The man was Giuseppe Ungaretti and, with his blazing grin, his impulsiveness and his habit of flying noisily off the handle, he was – to the foreign eye – as Italian as his name suggests; as Italian as mozzarella cheese.

But in 1915 Italy was a new and artificial nation: the so-called “geographical expression”, composed of half a dozen kingdoms, duchies and Austro-Hungarian provinces, had been bolted forcibly into a unitary state barely 60 years before. And like many other subjects of the new Kingdom of Italy, Ungaretti was deeply confused about his identity.

Born in Egypt to migrant parents from Tuscany, moving to Paris for its art, he had drifted to Turin to train as a schoolteacher, where he was quickly caught up in the febrile campaign for Italy – a bystander as its Triple Alliance partners, Austria and Germany, dived into the pan-European war – to join the fighting on the other side.

For the pro-war Italians, this was a fight for territory but it was also seen as a golden opportunity to forge the elusive Italian national identity: “In the furnace of war,” Mark Thompson writes in his history of the Italian front, The White War, “Italy’s provincial differences would blend and harden into a national alloy.”

And it is that problem of identity that explains why this dreamy and artistically-inclined 27-year-old enlisted as a private.

In December 1915 he was entrained with the Brescia Brigade of the 19th Infantry and dispatched to the Isonzo River in Italy’s far north-east. “I’m a lost soul,” he confessed to a friend. “Which people do I belong to? Where am I from? I have no place of my own in this world, no neighbours… I talk oddly; I’m a stranger. Everywhere. Am I going to destroy myself in the blaze of my desolation? And what if war ordains me an Italian?”

In a war of contending futilities, Italy’s role was arguably the most futile of the lot. She could have remained neutral and at peace throughout the conflict. She entered it with no casus belli of any sort, as a pure aggressor, betraying her allies in the process, and though the British and French were glad to have a new partner to keep the Austrians busy in the south, privately their contempt knew no bounds. For British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, Italy was “greedy and slippery … that most voracious, slippery and perfidious Power”. For Winston Churchill she was simply “the harlot of Europe”. But for Private Ungaretti and his comrades, intoxicated by the poetic, jingoistic rhetoric of Gabriele d’Annunzio and fired with the ambition of “redeeming” the Austrian lands with Italian populations, there were no doubts.

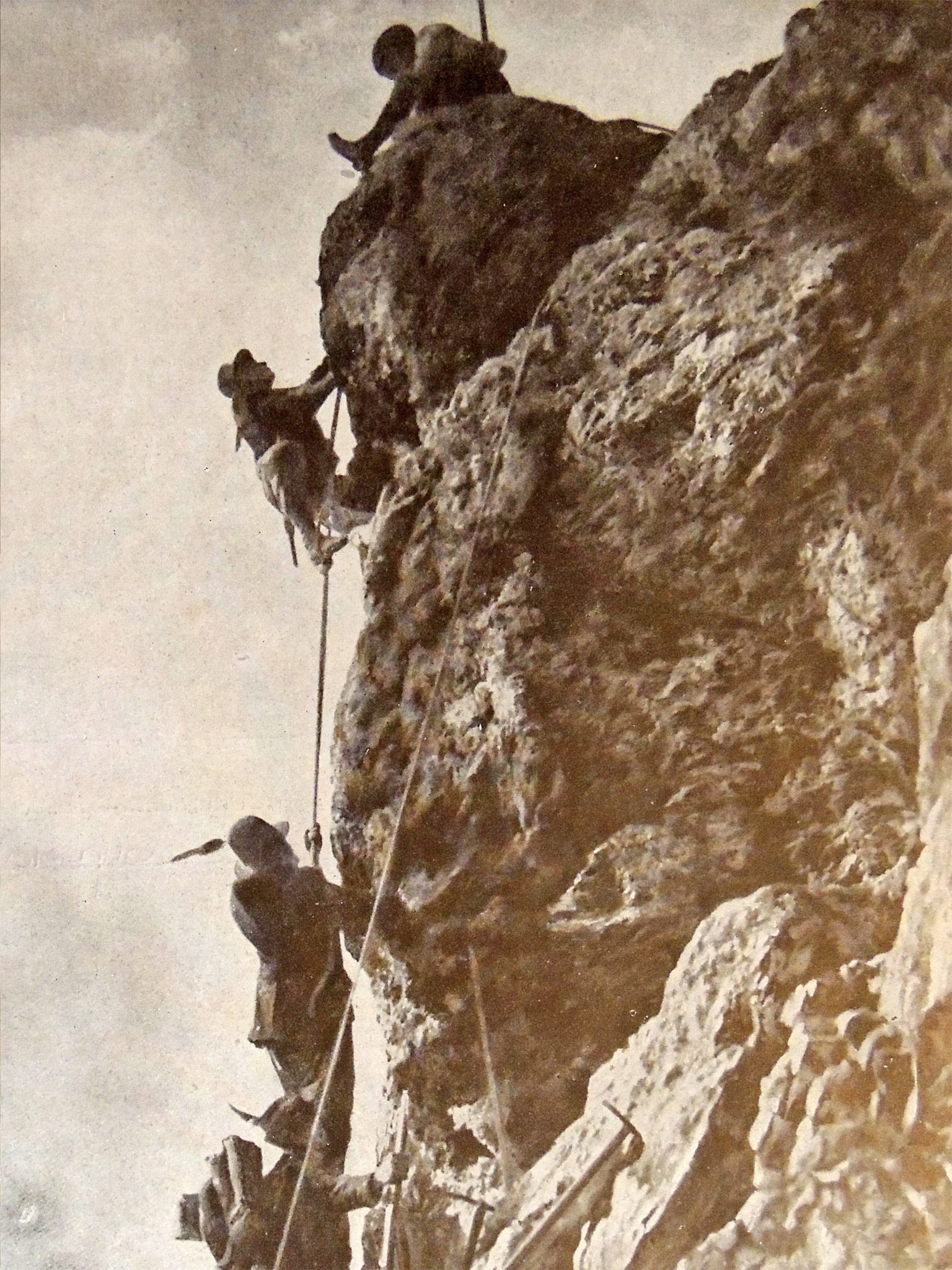

They found themselves fighting on a front as wretched, thankless and static as Flanders – and in some respects even worse. Their task was to cross the Isonzo River, which meanders southwards to the Adriatic, a few miles into Austrian territory, then storm the Carso, the treeless, limestone plateau beyond the river, at the top of which were heavily-armed Austrian defenders, with all the advantages of height and preparation. “The Carso,” Thompson writes, “might have been designed as the last place on earth for trench warfare.”

Digging trenches was impossible without drills, so the soldiers built low walls of loose stones. Shellfire shattered the stone into shrapnel which killed and maimed for hundreds of yards. “Imagine the flat or gently rolling horizon of Flanders,” Thompson writes, “tilting at 30 or 40 degrees, made of grey limestone that turns blinding white in summer.”

This was the brutal and unforgiving front at which Private Ungaretti spent the war. And it was here that he became a poet – one of Italy’s most revered of the 20th century. The D’Annunzio echo, the nationalistic dreams that impelled him to enlist, are nowhere to be found in the verse he wrote at the front.

In the blinding light of what came to be called “the white war”, those lies were vaporised. Ungaretti looked back at them ruefully:

Ungaretti/ man of sorrows/ an illusion’s enough/ to make you brave.

But if there is no jingo nonsense in his work, neither is there the disgust with war found in those British First World War poems. Instead, Ungaretti expresses a shocked, often ecstatic discovery of himself, his fellow men on both sides and the vastness and mystery of the universe.

These are not so much war poems as a soldier’s poems, in which the war’s intensity acts like a rocket under his creative powers. In the process, Ungaretti became a kind of secular mystic. Here, amid squalor and death, he discovered his essential nature.

“Liberty is in us,” he wrote to a friend. “I’ve lain down on muddy stones where mice the size of cats run over me as if I’m one of them, while the lice – charming creatures, tenacious as Germans – chewed on us contentedly.

“But my imagination had nothing to feed on except contemplation of itself, rejoicing that I’m still myself.” As his nationalistic motivation for enlisting showed, Ungaretti was politically naive and after the war he became an enthusiastic follower of Mussolini.

Despite this he was later rehabilitated and died in 1970, laden with honours. He said of his war poetry: “There is no trace [in it] of hatred for the enemy or anyone else. There’s an awareness of the human condition, men’s brotherhood in suffering, the extreme precariousness of their situation.”

The war on the Isonzo front dragged on and on – there were 12 battles in all. Italy started with a big advantage in troop numbers but sluggish command and chaotic organisation prevented an early breakthrough. A war of attrition followed.

The sixth battle, in August 1916, yielded the Austrian town of Gorizia, but otherwise there would be only disasters, including a series of avalanches in December 1916 that killed 10,000.

By then, the river had become shorthand for military stalemate.

But for Ungaretti it had a different meaning, inspiring one of his most famous poems, “The Rivers”, in which the Isonzo brings him back to life, reviving memories of the other rivers which had succoured him: the Serchio in Tuscany, where his parents originated, the Nile near which he was born, the Seine, where he discovered himself as an artist:

This morning I lay back/in an urn of water,/and like a relic/took my rest/ The Isonzo’s flow/smoothed me/ like a stone of its own/ here I best/recognise myself:/a yielding fibre/of the universe

In the stuttered lines of “Brothers”, Ungaretti captured the terror and comradeship of the trenches:

What’s your regiment/brothers?/ Word trembling/in the night/ Leaf barely born/ In the tortured air/involuntary revolt/of man facing his own frailty/ Brothers

But once you got above the smoke, the air cleared and you could see the whole world.

Standing in a quiet village, gazing at the vast panorama of mountains, he wrote the seven syllables of “Morning”.

Japanese in its compression, it is Italy’s best-known modern poem:

M’illumino/d’immenso (“I flood myself with the light of the immense.”)

Tomorrow: The great bombardment of Verdun

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments