A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Helen Thomas's final farewell to her husband, the poet Edward Thomas - ‘I stood at the gate watching him go. He turned back to wave until the mist and hill hid him...’

Millions experienced the emotional turmoil of loved ones leaving for the front line. Few captured the poignancy so heartbreakingly as Helen Thomas, wife of poet Edward Thomas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Christmas had come and gone. The snow still lay deep under the forest trees, which tortured by the merciless wind moaned and swayed as if in exhausted agony.

The sky, day after day, was grey with snow that fell often enough to keep the surface white, and cover again and again the bits of twigs, and sometimes large branches that broke from the heavily laden trees.

We wearied for some colour, some warmth, some sound, but desolation and despair seemed to have taken up her dwelling-place on the earth, as in our hearts she had entered, do what we would to keep her out. I longed with a passionate longing for some sign of life, of hope, of spring, but none came, and I knew at last none would come.

The last two days of Edward’s leave had come. Two days and two nights more we were to be together...

The first days had been busy with friends coming to say goodbye, all bringing presents for Edward to take out to the front – warm, lined gloves, a fountain pen, a box of favourite sweets, books.

Everyone who came was full of fun and joking about his being an officer after having had, as it were, to go to school again and learn mathematics, which were so uncongenial to him... They joked about his short hair, and the little moustache he had grown, and about the way he had perfected the Guards’ salute.

We got large jugs of beer from the inn nearby to drink his health in, and an end to the war.

The hateful cottage became homely and comfortable under the influence of these friends, all so kind and cheerful.

Then in the evenings, when just outside the door the silence of the forest was like a pall covering too heavily the myriads of birds and little beasts that the frost had killed, we would sit by the fire with the children and read aloud to them, and they would sing songs that they had known since their babyhood, and

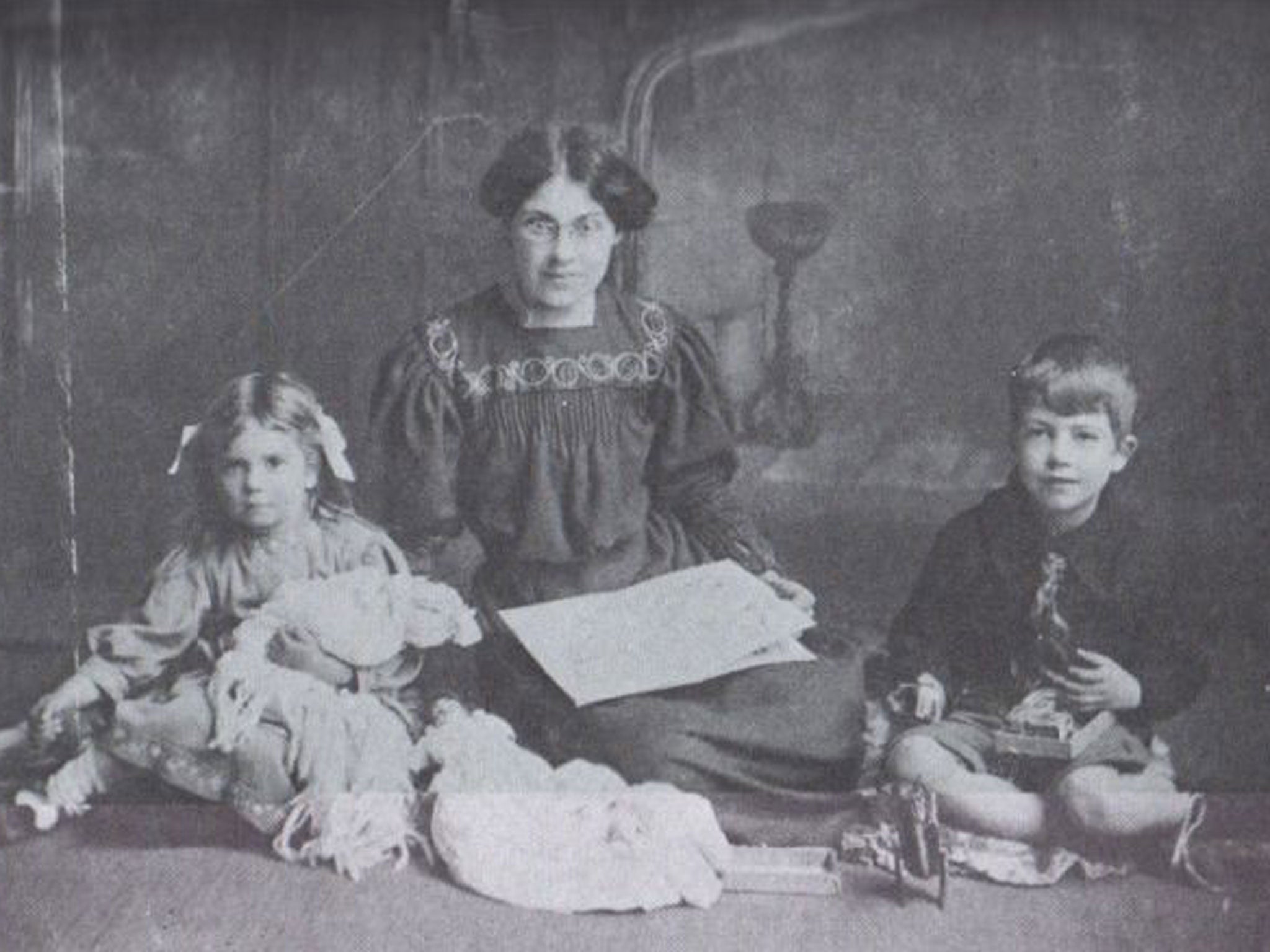

Edward sang new ones he had learnt in the army – jolly songs with good choruses in which I, too, joined as I busied about getting the supper. Then, when Myfanwy had gone to bed, Bronwen would sit on his lap, content just to be there, while he and Merfyn worked out problems or studied maps.

It was lovely to see those two so united over this common interest. But he and I were separated by our dread, and we could not look each other in the eyes...

The days had passed in restless energy for us both. He had sawn up a big tree that had been blown down at our very door, and chopped the branches into logs, the children all helping.

The children loved being with him, for though he was stern in making them build up the logs properly, and use the tools in the right way, they were not resentful of this but tried to win his rare praise and imitate his skill. Indoors he packed his kit and polished his accoutrements.

He loved a good piece of leather, and his Sam Browne and high trench-boots shone with a deep, clear lustre. The brass, too, reminded him of the brass ornaments we had often admired when years ago we had lived on a farm and knew every detail of a plough-team’s harness.

We all helped with the buttons and buckles and badges to turn him out the smart officer it was his pride to be. For he entered into this soldiering which he hated in just the same spirit of thoroughness of which I have spoken before.

We talked, as we polished, of those past days: “Do you remember when Jingo, the grey leader of the team, had colic, and Turner the ploughman led her about Blooming Meadow for hours, his eyes streaming with tears because he thought she was going to die? And how she would only eat the hay from Blooming Meadow, and not the coarse hay that was grown in Sixteen Acre Meadow for the cows?

“And do you remember Turner’s whip which he carried over his shoulder when he led Darling and Chestnut and Jingo out to the plough? It had 14 brass bands on the handle, one for every year of his service to the farm.”

So we talked of old times that the children could remember.And the days went by till only two were left. Edward had been going through drawers full of letters, tearing up dozens and keeping just one here and there, and arranging manuscripts and notebooks and newspaper cuttings all neatly in his desk – his face pale and suffering while he whistled.

The children helped and collected stamps from the envelopes, and from the drawers all sorts of useless odds and ends that children love. Merfyn knew what it all meant, and looked anxiously and dumbly from his father’s face to mine.

And I knew Edward’s agony and he knew mine, and all we could do was to speak sharply to each other: “Now do, for goodness sake, remember, Helen, that these are the important manuscripts, and that I’m putting them here, and that this key is for the box that holds all important papers like our marriage certificate and the children’s birth certificates, and my life-insurance policy. You may want them at some time, so don’t go leaving the key about.”

And I, after a while: “Can’t you leave all this unnecessary tidying business, and put up that shelf you promised me? I hate this room but a few books on a shelf might make it look a bit more human.”

“Nothing will improve this room, so you had better resign yourself to it. Besides, the wall is too rotten for a shelf.”

“Oh, but you promised.”

“Well, it won’t be the first time I’ve broken a promise to you, will it! Nor the last, perhaps.”

Oh, God! melt the snow and let the sky be blue.

The last evening comes. The children have taken down the holly and mistletoe and ivy, and chopped up the little Christmas tree to burn. And for a treat Bronwen and Myfanwy are to have their bath in front of the blazing fire. The big zinc bath is dragged in, and the children undress in high glee, and skip about naked in the warm room, which is soon filled with the sweet smell of the burning greenery.

The berries pop and the fir tree makes fairy lace, and the holly crackles and roars. The two children get in the bath together, and Edward scrubs them in turn –they laughing, making the fire hiss with their splashing. The drawn curtains shut out the snow and the starless sky, and the deathly silence out there in the biting cold is forgotten in the noise and warmth of our little room.

After the bath Edward reads [to] them. First of all he reads Shelley’s The Question and Chevy Chase, and for Myfanwy a favourite Norse tale. They sit in their nightgowns listening gravely, and then, just before they kiss him good night, while I stand with the candle in my hand, he says: “Remember while I am away to be kind. Be kind, first of all, to Mummy, and after that be kind to everyone and everything.”

And they all assent together, and joyfully hug and kiss him, and he carries the two girls up, and drops each in her bed.

And we are left alone, unable to hide our agony, afraid to show it. Over supper, we talk of the probable front he’ll arrive at, of his fellow officers, and of the unfinished portrait-etching that one of them has done of him and given to me. And we speak of the garden, and where this year he wants the potatoes to be, and he reminds me to put the beans in directly the snow disappears...

He reads me some of the poems he has written that I have not heard – the last one of all called Out in the Dark. And I venture to question one line, and he says: “Oh, no, it’s right, Helen, I’m sure it’s right.”

And I nod because I can’t speak, and I try to smile at his assurance.

I sit and stare stupidly at his luggage by the wall, and his roll of bedding, kit bag, and suitcase. He takes out his prismatic compass and explains it to me, but I cannot see, and when a tear drops onto it, he just shuts it up and puts it away.

Then he says, as he takes a book out of his pocket: “You see, your Shakespeare’s Sonnets is already where it will always be. Shall I read you some?”

He reads one or two to me. His face is grey and his mouth trembles, but his voice is quiet and steady. And soon I slip to the floor and sit between his knees, and while he reads his hand falls over my shoulder and I hold it with mine.

“Shall I undress you by this lovely fire and carry you upstairs in my khaki greatcoat?” So he undoes my things, and I slip out of them; then he takes the pins out of my hair, and we laugh at ourselves for behaving as we so often do, like young lovers.

“We have never become a proper Darby and Joan, have we?”

“I’ll read to you till the fire burns low, and then we’ll go to bed.”

Holding the book in one hand, and bending over me to get the light of the fire on the book, he puts his other hand over my breast, and I cover his hand with mine, and he reads from Antony and Cleopatra. He cannot see my face, nor I his, but his low, tender voice trembles as he speaks the words so full for us of poignant meaning. That tremor is my undoing.

“Don’t read any more. I can’t bear it.”

All my strength gives way. I hide my face on his knee, and all my tears so long kept back come convulsively. He raises my head and wipes my eyes and kisses them, and wrapping his greatcoat round me carries me to our bed in the great, bare ice-cold room.

Soon he is with me, and we lie speechless and trembling in each other’s arms. I cannot stop crying. My body is torn with terrible sobs. I am engulfed in this despair like a drowning man by the sea. My mind is incapable of thought.

Only now and again, as they say drowning people do, I have visions of things that have been – the room where my son was born; a day, years after, when we were together walking before breakfast by a stream with hands full of bluebells; and in the kitchen of our honeymoon cottage, and I happy in his pride of me.

Edward did not speak except now and then to say some tender word or name, and hold me tight to him.

“I’ve always been able to warm you, haven’t I?”

“Yes, your lovely body never feels as cold as mine does. How is it that I am so cold when my heart is so full of passion?”

“You must have Bronwen to sleep with you while I am away. But you must not make my heart cold with sadness, but keep it warm, for no one else but you has ever found my heart, and for you it was a poor thing after all.”

“No, no, no, your heart’s love is all my life. I was nothing before you came and would be nothing without your love.”

So we lay, all night, sometimes talking of our love and all that had been, and of the children, and what had been amiss and what right. We knew the best was that there had never been untruth between us. We knew all of each other, and it was right. So talking and crying and loving in each other’s arms we fell asleep...

Edward got up and made the fire and brought me some tea, and then got back into bed, and the children clambered in, too, and sat in a row sipping our tea. I was not afraid of crying any more. My tears had been shed, my heart was empty, stricken with something that tears would not express or comfort. The gulf had been bridged. Each bore the other’s suffering.

We concealed nothing, for all was known between us. After breakfast, while he showed me where his account books were and what each was for, I listened calmly, and unbelievingly he kissed me when I said that I, too, would keep accounts.

“And here are my poems. I’ve copied them all out in this book for you and the last of all is for you. I wrote it last night, but don’t read it now... It’s still freezing. The ground is like iron, and more snow has fallen. The children will come to the station with me; and now I must be off.”

We were alone in my room. He took me in his arms, holding me tightly to him, his face white, his eyes full of a fear I had never seen before. My arms were around his neck.

“Beloved, I love you,” was all I could say.

“Helen, Helen, Helen,” he said, “remember that, whatever happens, all is well between us for ever and ever.”

And hand in hand we went downstairs and out to the children, who were playing in the snow.

A thick mist hung everywhere, and there was not sound except, far away in the valley, a train shunting. I stood at the gate watching him go; he turned back to wave until the mist and the hill hid him.

I heard his old call coming up to me: “Coo-ee!” he called.

“Coo-ee!” I answered, keeping my voice strong to call again. Again through the muffled air came his “Coo-ee”. And again went my answer like an echo.

“Coo-ee” came fainter next time with the hill between us, but my “Coo-ee” went out of my lungs strong to pierce to him as he strode away from me.

“Coo-ee!” So faint now it might only be my own call flung back from the thick air and muffling snow. I put my hands up to my mouth to make a trumpet, but no sound came. Panic seized me, and I ran through the mist and the snow to the top of the hill, and stood there a moment dumbly, with straining eyes and ears. There was nothing but the mist and the snow and the silence of death. Then with leaden feet which stumbled in a sudden darkness that overwhelmed me I groped my way back to the empty house.

Edward Thomas was killed at the Battle of Arras on 9 April 1917.

Extract taken from “World Without End”, by Helen Thomas (first published by William Heinemann Ltd, 1931; reprinted by Carcanet, 1987), by kind permission of Mrs Rosemary Vellender

Tomorrow: The soldiers and the letter-writer

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments