A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: Campaign for peace turned former hero into public enemy No 1

Edmund Morel exposed the truth about the Congo. But then he turned to the causes of the war

“With a clang, the gates spring open and inward. The fog rushes in, in eddying billows. But through it there comes the sound of a beloved voice…”

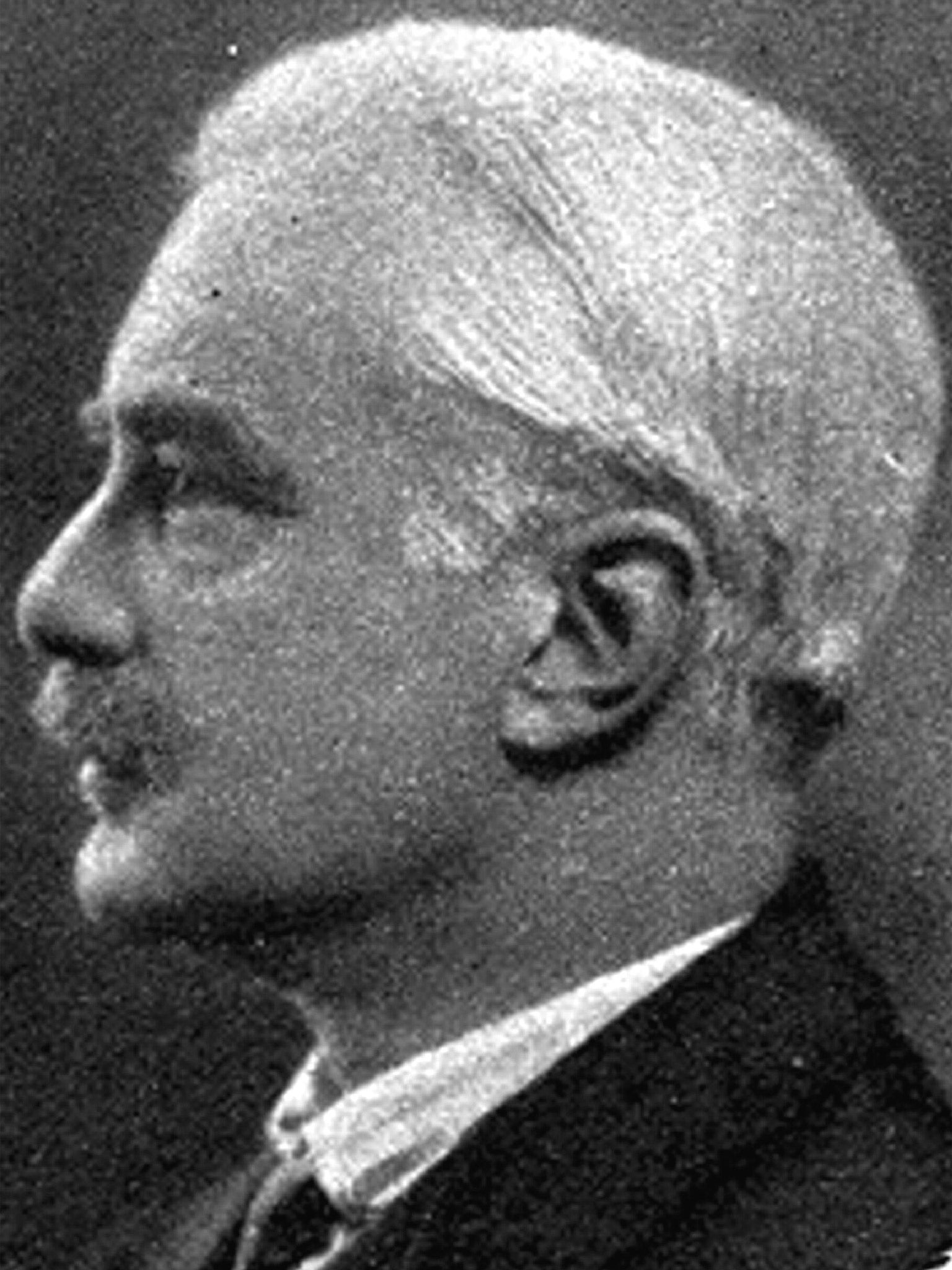

The “beloved voice” that Edmund Morel heard as he left Pentonville prison, at the end of January 1918, was that of his wife Mary, who stood by him steadfastly through the worst ordeal of his life, as he fell in popular esteem from being hero to public enemy.

ED Morel had established himself early in the 20th century as the greatest investigative journalist of his time. While working as a shipping clerk in Liverpool and Belgium, he studied the cargoes coming in and out of Antwerp and had deduced that something terrible was happening in the Congo, from which somebody else was skimming vast profits. His campaign to expose slavery and corruption in the land that Joseph Conrad called the Heart of Darkness earned ED Morel international renown and the respect of the British authorities.

There was a very different reaction to the next campaign in which he immersed himself. Though he was not a pacifist, he believed from the start that the 1914-18 war was an unnecessary slaughter, that no principle was at stake, and that the British public was not being told the truth about why they were fighting. He thought it was cant for the UK to claim to be fighting for freedom and democracy when it was allied to Russia, and suspected that the real explanation lay in secret treaties. His wartime essay Ten Years of Secret Diplomacy was later acknowledged by AJP Taylor as the foundation for all subsequent research into the causes of the war.

Morel had another quality in addition to being a prolific writer – he was a skilful organiser. As disparate anti-war groups ranging from the Quakers to the left of the Labour Party came together in the Union of Democratic Control, Morel was the natural choice for secretary.

Under his guidance, the UDC focused its attack on the causes of war, and on preventing the next war, rather than campaigning directly against the ongoing slaughter. In that way, Morel made the job of the authorities harder. They never did find a pretext on which to proscribe the organisation and struggled to work out how to silence Morel.

Harassment did not work. Scotland Yard opened his mail and tapped his telephone. UDC meetings were attacked by mobs who tore down banners, threw stink bombs, and assaulted participants. Soon, it became impossible for them to rent a hall in London. Donald Mitchell, in his recently published biography of Morel, “The Politics of Dissent”, tells how Morel became so used to being shunned by old friends that when a former journalist colleague in military uniform greeted him in the street, he was so surprised and grateful that he burst into tears.

Meanwhile, in Whitehall, they hunted for an excuse to prosecute the nation’s most effective anti-war campaigner. Eventually, they seized upon a letter Morel had written to Ethel Sedgwick, niece by marriage of the former Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, asking her to sneak a copy of one of his pamphlets into Switzerland to give to the French anti-war writer, Romain Rolland.

This was deemed to be an offence under the Defence of the Realm Act, and Morel was sentenced to six months in prison. Despite a petition to the Home Secretary, he was classed as a “second division” prisoner, which meant he was allowed to write and receive just one letter and have one 15-minute visit at the end of each full calendar month he had spent inside. During daylight, he was allowed an hour’s exercise in the cell yard, and was required to sew canvas mailbags and weave rope into hammocks and mats for the navy. From 4pm to 8am he was held in solitary confinement, in cold such as he never experienced before, in a cell next-door to that of a prisoner who had raped a child.

His wife and other sympathisers became concerned about the 44-year-old man’s physical and mental health. In one of the four letters he was allowed to write, he referred disturbingly to a strange dream he had had about winning the Nobel Prize. He was also reputed to have had some kind of hallucination about being visited by the murdered French socialist, Jean Jaurès.

The Home Secretary, Sir George Cave, was bombarded with appeals from Morel’s small but dedicated band of supporters, but ignored them until the prisoner had almost completed his sentence, when Sir George magnanimously ruled that he could be released three days early.

The pacifist Bertrand Russell, who saw Morel two months after his release, noted that “his hair was completely white (there was hardly a tinge of white before). When he first came out, he collapsed completely, physically and mentally.”

Yet there were some who thought he had not suffered enough. In the Commons, on 14 February, Colonel Walter Faber, Conservative MP for Andover, furiously asked why Morel had been let free at all. Another Tory, William Joynson-Hicks, wanted him stripped of his citizenship.

But to the Labour Party, he was a hero. In 1922, he had the satisfaction of taking a seat in Dundee off Winston Churchill, whom he heartily despised. Two years later, he was walking in woodland when he felt tired, sat down by a tree, and died – a death hastened by his prison ordeal.

Tomorrow: Triumph of the Suffragettes

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks