A History of the First World War in 100 Moments: A desert uprising that began in hope but was doomed to end in betrayal

Robert Fisk on the moment the Arabs, trusting in British good faith, turned on their Turkish rulers

The Arab Revolt is all about the Arab Betrayal. The blowing up of Turkish trains, the capture of Aqaba, the camel charges and the slaughter on the Road to Damascus, and the mythistory of Lawrence of Arabia are the Cinemascope version of the First World War in the desert. Better to watch Peter O’Toole in the movie.

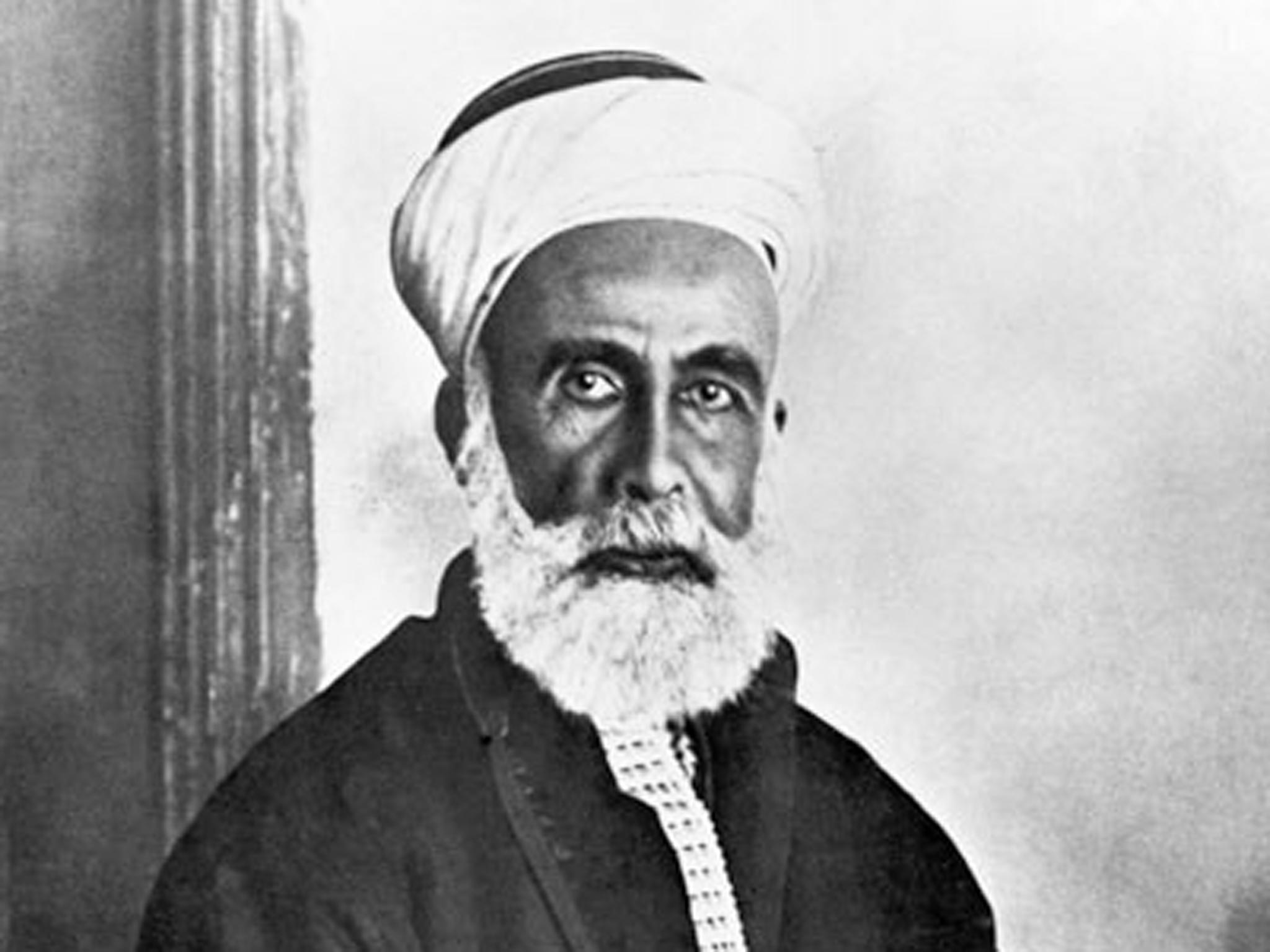

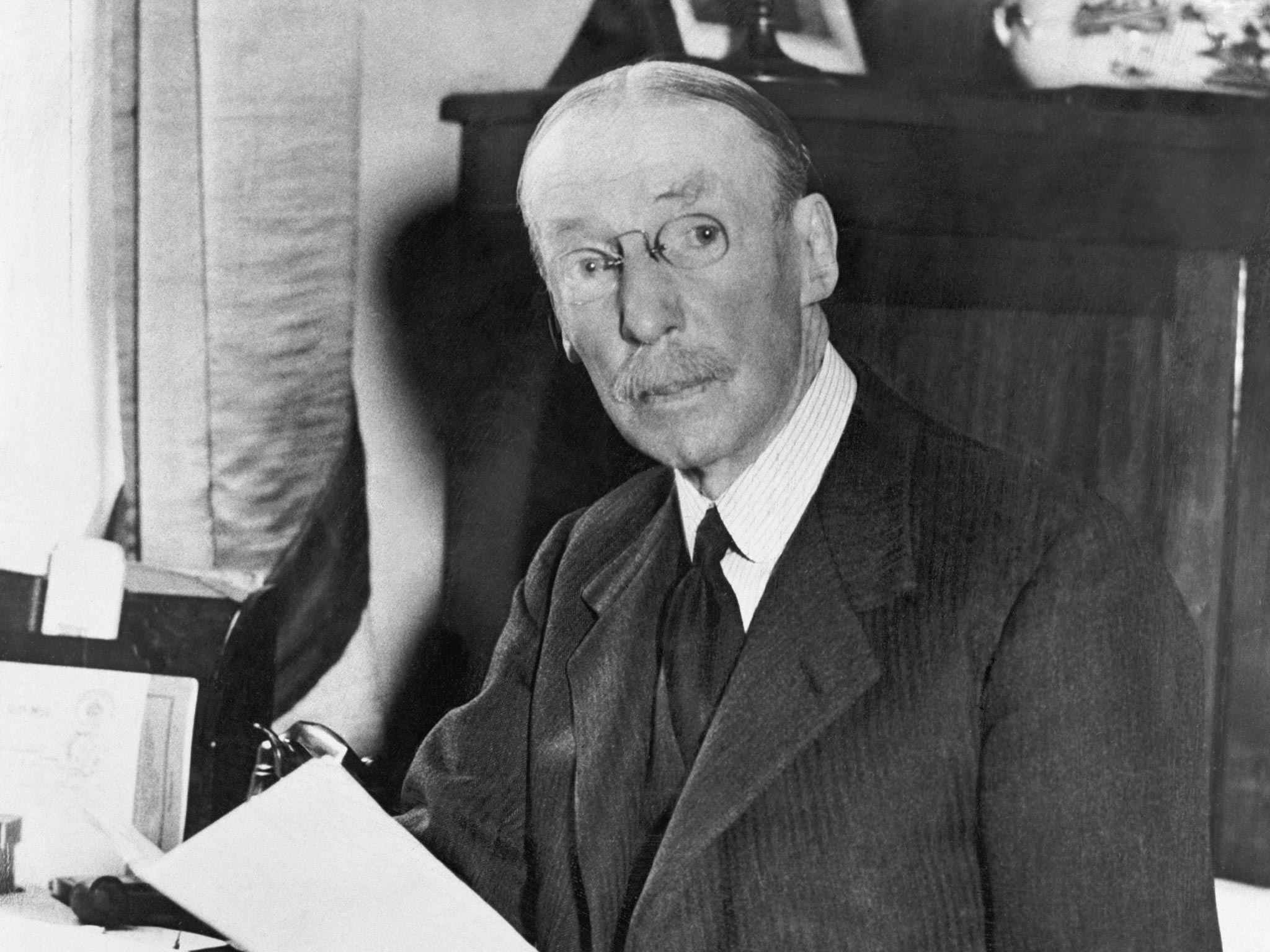

Best to start our story with the 1915 correspondence sent to Sharif Hussain – the religious leader of Mecca and Medina whose Hashemite family had guarded the Islamic holy land since the 10th century – by the British minister in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon.

Hussain proposed to rise up with his tribes against the Ottoman Turks in Arabia and McMahon addressed his would-be Arab ally in the following terms: “To the excellent and well-born Sayed, the descendant of Sharifs, the Crown of the Proud, Scion of Mohamed’s Tree and Branch of the Quraishite Trunk, him of the Exalted Presence and of the Lofty Rank… His Excellency the Sharif Hussain, Lord of the Many, Emir of Mecca the Blessed, the lodestar of the Faithful and the cynosure of all devout Believers, may his Blessing descend upon the people in their multitude.”

Which shows that the Brits did not really understand the Arabs. But the Arabs understood the Brits. “Our aim, O respected Minister,” Hussain archly replied, “is to ensure that the conditions which are essential to our future shall be secured on a foundation of reality, and not on highly decorated phrases and titles.”

The “conditions” were those of the so-called Damascus Protocol which Hussain’s son Faisal – rightly suspicious of the British, and under pressure to join the Ottoman “jihad” against the Allies – agreed must include the post-war independence of all Arab countries inside an area bordered by southern Turkey, the Persian (Iranian) frontier, the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea and the Mediterranean; in other words, the Arab Middle East including the Gulf and all those nations-to-be which we now call Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Iraq.

The catch, of course, was that while the Brits – faced with the new killing fields of the Western Front and the subsequent disaster at Gallipoli – would promise almost anything to get the Arabs on side, they would also make promises to others. But they later divvied up mandates with the French – in secret – for Palestine, Transjordan, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, while promising – in public – British support for a Jewish “homeland” in Palestine.

Promises are meant to be kept. But the British had promised everything to everyone. Upon this folly was constructed the Arab Revolt, whose warriors – ultimately commanded by Lawrence’s favourite Sharifian son, Faisal – fought with much courage and many bags of British gold to destroy the Turkish army. The only real problem was the bit about Arab “independence”.

Nevertheless, the Arab Revolt that started in the Hejaz in June 1916 would have a religious foundation. Faisal’s men – deserting and returning, accruing temporary auxiliaries from tribes, recruiting with British cash – would have to fight their way through 1,000 miles of Turkish Ottoman territory to reach Damascus and Aleppo. Attempts to seize Medina failed, but when the Arabs, with the Boy’s Own enthusiasm of British officers that included Lawrence, turned upon the only rail link to Damascus and the north in 1917, legend and history came together. Spread out over hundreds of miles, the Turkish military – like the Americans in Iraq 90 years later – could not secure their communications. Thus the Arabs would tie down the Turks in their garrisons by blasting their steam locos off the track and killing the soldiers – and sometimes the civilians – travelling in the carriages behind them.

Once the Sykes-Picot agreement to share the Middle East between Britain and France was revealed – courtesy of Russian revolutionaries – Faisal and Lawrence realised that the only hope for the “independence” which they believed the Arabs deserved and had been promised lay in a ruthless assault across the deserts to the north in the hope of capturing Damascus. This they accomplished – with courage, brutality and a few war crimes (in which Lawrence was himself involved) on the way, to match the equal cruelty of the Turks. The British and Commonwealth armies smashed their way up the Mediterranean coast under General Allenby while the Arabs raced north inland.

Lawrence understood the duplicity in which he was involved. In a note he sent to his headquarters in Cairo, he wrote that he hoped to be killed on the road to Damascus because “we are calling them [the Arabs] to fight for us on a lie, and I can’t stand it”. And sure enough, no sooner did Faisal arrive in Damascus than the British reneged on their promise of independence. As his own Arab fighters, along with the Syrian resistance to Ottoman rule, poured into the city, Allenby met Faisal at the Victoria Hotel. Faisal and Lawrence now regarded Sykes-Picot as a dead letter, outdated by the sheer speed of the Arab advance. Not so, said Allenby: France would be the “protecting power” in Syria. And Faisal’s territory would include neither Palestine nor Lebanon. Had Lawrence not told Faisal that the French would be the “protecting” power? “No, Sir,” replied Lawrence. “I know nothing about it.” Or did he?

Thus the Great Betrayal was made manifest. When Faisal’s men raised the Sharifian standard over Beirut, it was torn down. Humiliated as a nuisance at the Versailles peace conference, Faisal returned to Damascus where his government was overthrown and his tiny army, including veterans of the Revolt, was annihilated by French troops at the 1920 Battle of the Maysalun Pass, Arab horsemen charging French tanks – much as the Poles were to charge the German Panzers 19 years later.

As a consolation prize, Faisal was given Mesopotamia (Iraq), his brother Abdullah awarded the artificial sandpit of Jordan. Hussain, the “lodestar of the faithful”, was chucked out of Arabia by the House of Saud (later producers of oil and Osama bin Laden). Both Iraq and Syria fell to nationalist Baathists, Jordan would survive under the Hashemites, while Palestine turned into a hell-disaster, 750,000 of its Arabs driven from their homes to make way for the Jewish “homeland” which Britain had promised. Lebanon endured a 15-year civil war.

Lawrence was to write to Winston Churchill in 1921: “The Arabs are like a page I have turned over, and sequels are rotten things.” So much for the Arab Revolt.

Tomorrow: An Italian sniper fails

The '100 Moments' already published can be seen at: independent.co.uk/greatwar

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks