FBI closes case on the last skyjacker

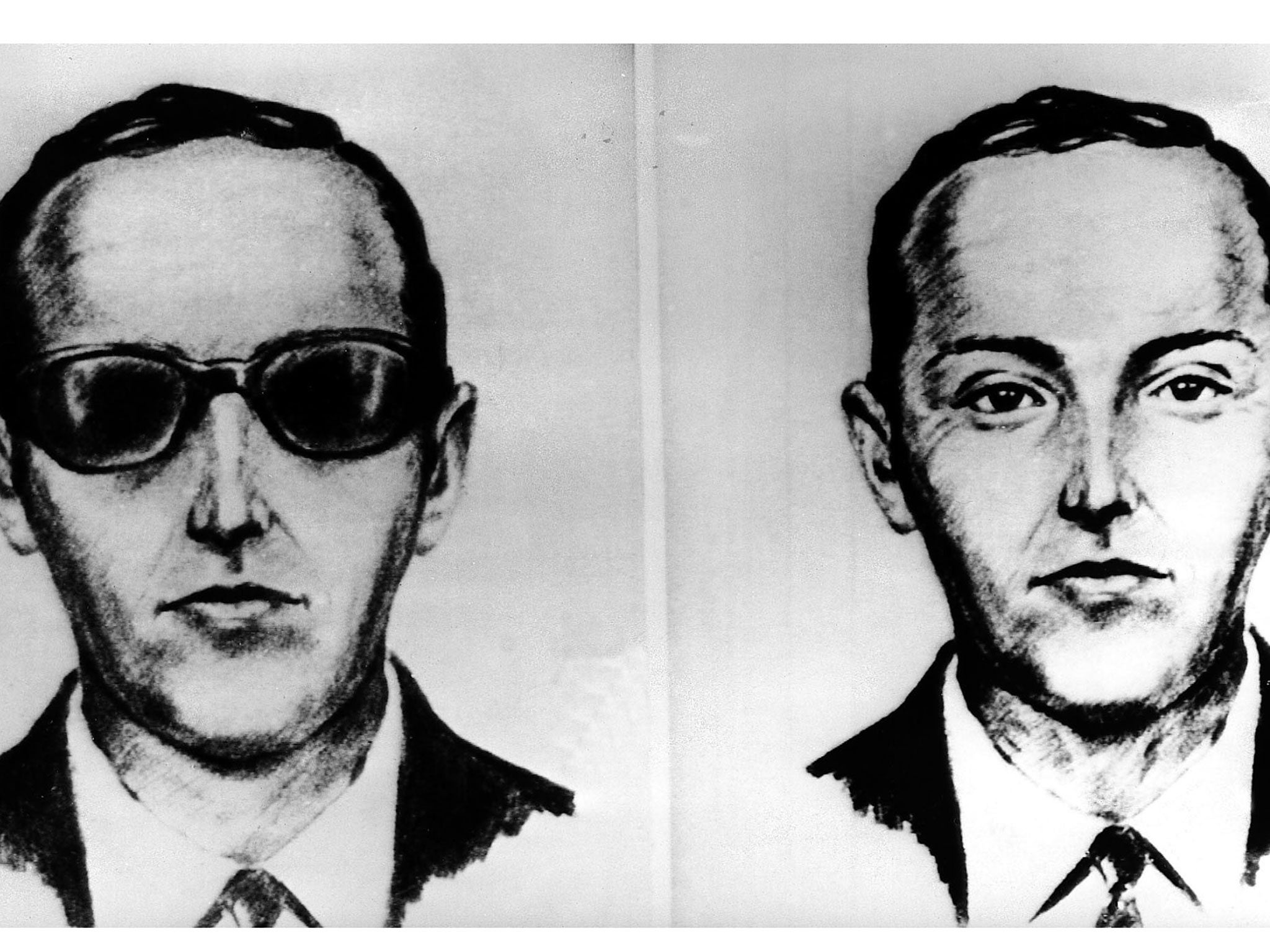

The myterious 'JB Cooper' was a US sensation in 1971, when he parachuted into the night with a $200,000 ransom. Now the FBI finally admits that the trail has gone cold

Of all America’s skyjackings, only one remains unsolved. The case has confounded FBI investigators for decades, and its astonishing details, clues and alleged participants have become the stuff of American criminal lore. The story has inspired songs, T-shirts and books; and the main character has, at times, bordered on American folk-hero status.

Now, after one of “the longest and most exhaustive investigations” in FBI history, the agency is finally moving on from the search for the infamous skyjacker known as DB Cooper, according to a statement released by the FBI. The riveting search – which Washington Post reporter Cynthia Gorney described as “Jesse James meets the Loch Ness monster” – is more or less over.

“During the course of the 45-year Norjak investigation, the FBI exhaustively reviewed all credible leads, co-ordinated between multiple field offices to conduct searches, collected all available evidence, and interviewed all identified witnesses,” the statement says. “Over the years, the FBI has applied numerous new and innovative investigative techniques, as well as examined countless items at the FBI Laboratory. Evidence obtained during the course of the investigation will now be preserved for historical purposes at FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC.”

The case began on the afternoon of 24 November 1971, when a man who went by the name DB Cooper used cash to buy a one-way ticket on Flight 305, bound for Seattle, according to an FBI statement. By the end of night, Cooper would vanish into thin air 10,000 feet above dense Washington State forestland with $200,000 in cash, appearing to pull off a heist so daring that he would eventually be considered the most infamous hijacker in American history.

The FBI describes Cooper as a “quiet man” in his mid-forties, who wore a business suit with a black tie and white shirt. After ordering a bourbon and soda, he passed a note to a stewardess that explained he had a bomb in his briefcase. “The stunned stewardess did as she was told,” the FBI statement notes. “Opening a cheap attaché case, Cooper showed her a glimpse of a mass of wires and red-coloured sticks and demanded that she write down what he told her. Soon, she was walking a new note to the captain of the plane that demanded four parachutes and $200,000 in $20 bills.”

After landing in Seattle, Cooper allowed 36 passengers to leave the plane in exchange for cash and several parachutes. He instructed the plane to take off again and head for Mexico City. A little after 8pm, between Seattle and Reno, according to the FBI, Cooper launched himself from the back of the plane with his money in hand. He was never seen again.

Originally, FBI investigators believed Cooper must have been an experienced skydiver, possibly with military experience. “But we concluded after a few years this was simply not true,” Special Agent Larry Carr said in 2007. (The FBI didn’t provide his first name.) “No experienced parachutist would have jumped in the pitch-black night, in the rain, with a 200-mile-an-hour wind in his face, wearing loafers and a trench coat. It was simply too risky. He also missed that his reserve chute was only for training and had been sewn shut – something a skilled skydiver would have checked.”

In a 1980 profile of Ralph Himmelsbach – the FBI’s lead investigator on the case at the time – the ageing lawman disputed the romantic idea that Cooper was a Robin Hood figure who gamed the system by pulling off an exquisite victimless crime. “‘Sleazy’ is the word the he uses, actually. A sleazy, rotten criminal.” (Himmelsbach turns downright eloquent when he gets going on this subject.) “Nothing heroic about him, nothing glamorous, nothing admirable at all. He jeopardised the lives of 40 people and I have no admiration at all. He was a stupid, selfish man...”

At the time, the writer noted, Himmelsbach was fielding calls from all over the country, responding to mail from as far away as Germany and investigating just about everything in between, including trousers “found slung on Washington treetops (hoax)” and “men too short and men too young and men whose alibis place them firmly far away from the North-west skies that night”. “Well over 1,000,” he has since said, tallying up his Cooper suspects to date. “Real, real good ones; real, real poor ones. A lot of both. And many in between.”

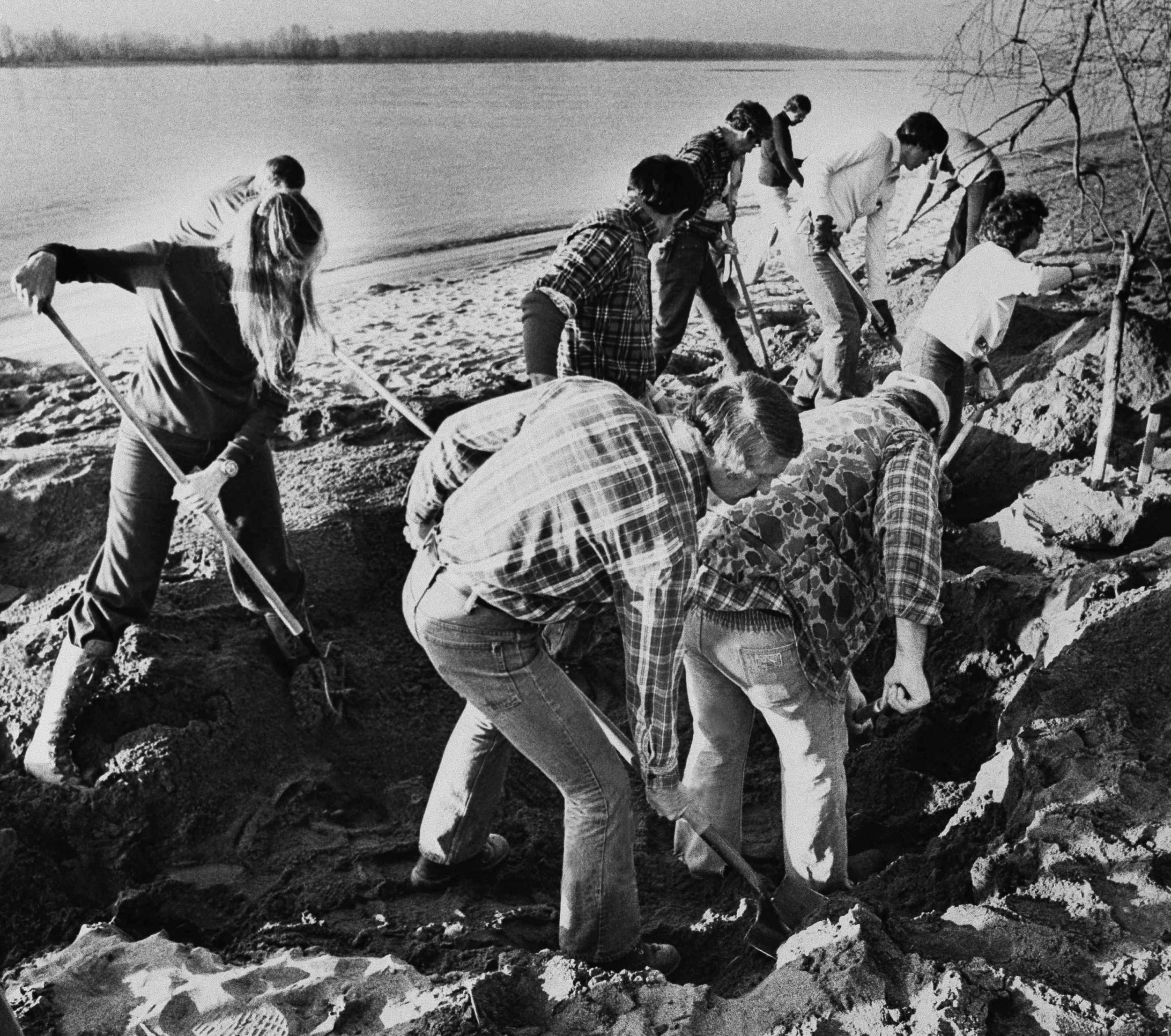

Nearly four decades and countless suspects later, not much has changed. Despite some tantalising clues discovered over the years – such as a rotting package containing $5,800 in $20 bills with serial numbers that matched the ransom money – many investigators believe Cooper never survived his plummet to the earth. His parachute wasn’t steerable and he would’ve landed in the wilderness wearing a suit and leather shoes in the winter time, at night. The area where the jump is thought to have occurred has been described as “a God-forsaken swathe of rugged Washington forest country”. “If there’s any place around you wouldn’t want to jump into, that’d be it,” an FBI investigator once said.

Years later, Carr agreed: “Diving into the wilderness without a plan, without the right equipment, in such terrible conditions, he probably never even got his chute open.” At the time, The Seattle Times reported, Carr was renewing his plea for new information in the case, possibly with the help of technology. While publicly brainstorming, he said he was hoping a clever hydrologist using satellite technology might find a way to trace the Cooper cash found on the Columbia River in 1980 back to the creek in which it originated. At the end, he noted, a body might be waiting. Perhaps, he said, somebody might remember something about an odd uncle. Almost a decade later, the thief remains at large.

“Although the FBI appreciated the immense number of tips provided by members of the public, none to date have resulted in a definitive identification of the hijacker,” the FBI’s latest statement says. “The tips have conveyed plausible theories, descriptive information about individuals potentially matching the hijacker, and anecdotes to include accounts of sudden, unexplained wealth. [But] every time the FBI assesses additional tips for the Norjak case, investigative resources and manpower are diverted from programs that more urgently need attention.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks