Fall of the Berlin Wall: Goodbye to all that - the lost world beyond the Iron Curtain

Germans who bemoan the failures of reunification might do better to remember how bad it actually was - and reflect on how far the country has come

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

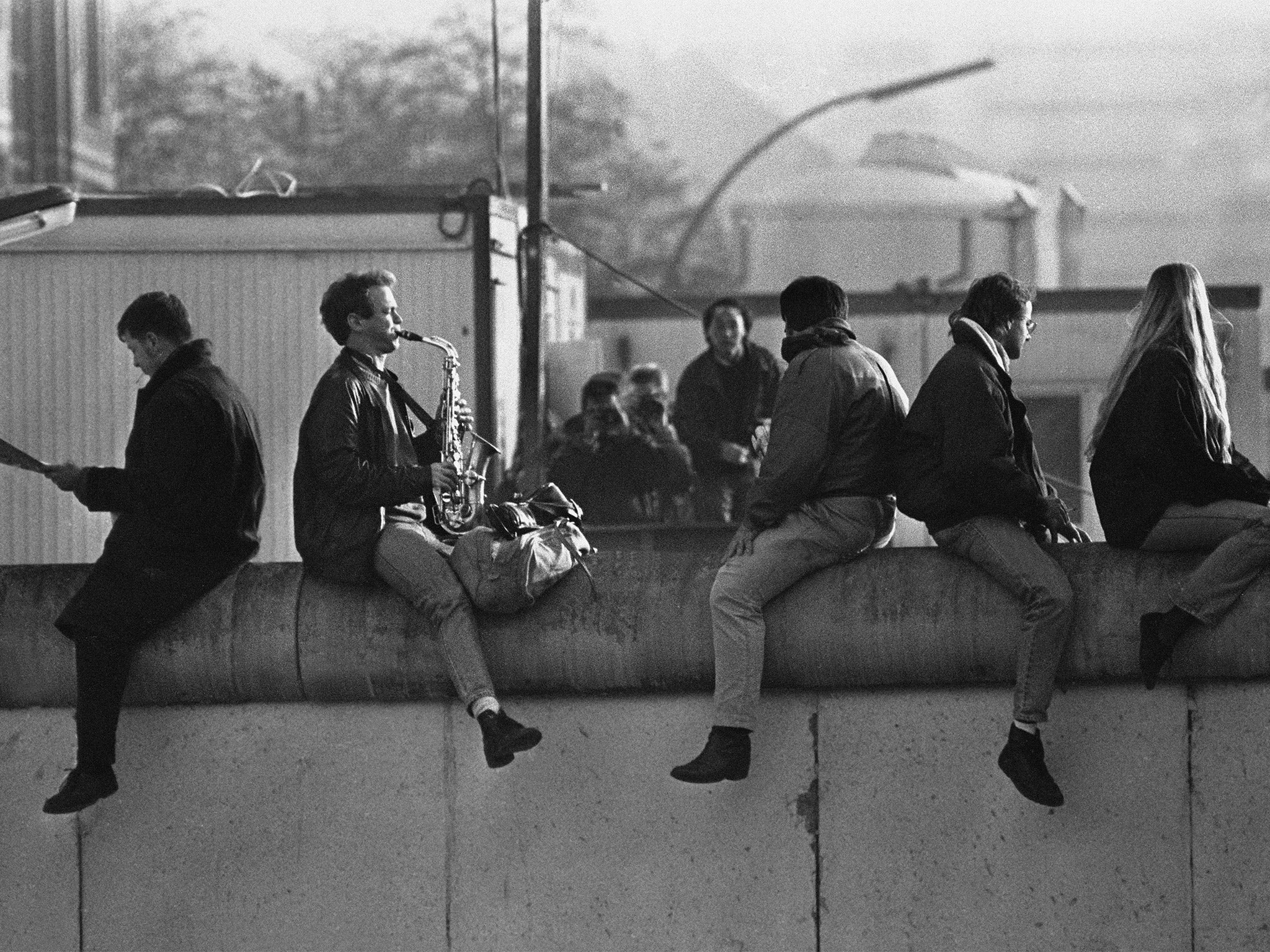

Your support makes all the difference.The fall of the Wall was the single event that signified the collapse of Communism in Europe – and it still does. No matter than the Soviet Union staggered on for more than two more years or that Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu had another two months to live. After the Wall had been transformed overnight from the Iron Curtain, penetrable only on pain of death, to a pile of graffiti-daubed rubble, picked over by souvenir hunters, the question was not whether European Communism was going to breathe its last, but when.

It is perhaps remarkable that a quarter of a century on there has been so little retrospection, except about what happened that one night. Not only is East Germany no more – a country that was, after all, internationally recognised as a sovereign state – but all the countries that made up what was then the Warsaw Pact and the republics that made up the Soviet Union have been transformed, some almost beyond recognition and most to an astonishing and often unappreciated degree.

The extent to which, individually and collectively, people banish a difficult past may be underestimated. Children of Holocaust survivors sometimes observe that their mother or father told them next to nothing about what they had endured or the world they had left behind. They shook the dust off their feet, buried the experience deep inside their minds, and got on with their lives, seeking to make up, in a way, for lost time and to validate their survival. It was left to the next and subsequent generations to re-visit the reality and keep the memory.

You find a milder expression of the same phenomenon among those who lived behind the Iron Curtain. There is not much looking back among the over-40s, say, in East and Central Europe, still less are they inclined to make comparisons between then and now. Where comparisons are made, they are often of the nostalgic kind: the solidarity that some enjoyed in adversity (those who were not informing on each other); the social safety-net – however inadequate it really was; the convenience of state nursery provision, the camaraderie of summer camps, and good quality higher education, especially in the sciences.

Naturally, perhaps, the memories that tend to be articulated most vividly are mostly of the glory days: the cutting of the barbed wire at the east-west border in Hungary; the brief uprising in Romania; Solidarity’s election victory in Poland; Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution; and, in Russia, Boris Yeltsin’s victory over the coup plotters.

But nothing, either before or afterwards, really compared to Berlin. Ronald Reagan’s seemingly fantastical call to Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall” had been answered. A little more than two years later, amid much bewilderment and administrative confusion, Germans did just that.

A quarter of a century on, the euphoria of those days is remembered and joyfully relived, but it coexists with a sense of disappointment that the two halves of Germany have not knitted together more conclusively than they have. For all the massive investment in the former east – bought in part at the expense of delayed maintenance and development in the former west – there are still gaps in the centre of Berlin, where no-man’s-land used to run; there is still dereliction on the fringes of many exquisitely restored east German towns and cities. And it is possible to sense, deep down, still entrenched psychological differences. But how could there not be, after the multiple trauma of military defeat, Soviet occupation, Communist rule, being severed from the West, and then – half a century later – the experience of the whole edifice falling apart?

In many respects, however, the despondency of some Germans about their enduring divisions seems misplaced. To an outsider – but frequent visitor – such as myself, the country and the people seem to have come together more successfully than the rest of Eastern and Western Europe. Today’s Germans, I would suggest, suffer some of the same selective memory syndrome as others who lived either side of the east-west divide. They forget how deep the divisions actually were between the Federal Republic and the GDR.

I first went to Germany – East and West – as a teenager, with my family, by car, on an expedition long planned by my father, to visit the family he had stayed with on a school exchange just before the war. It was not just the contrast in the appearance and living standards of the two halves that was so evident – from western colour, vibrancy and hope to eastern grey and stoical gloom. There was the actual experience of the border crossing: the layers of barbed wire and trenches; the mirrors wheeled under our car; the searches of its interior (which the armed border guards practically dismantled); and a night at the Adlon hotel in (East) Berlin, in rooms that looked out on floodlit fortifications like something out of a war film.

Our destination was the Hanseatic port of Stralsund, which is now – as it happens – Angela Merkel’s constituency. The family flat where my father had stayed as a schoolboy had been divided and was now a communal flat in the Soviet manner, with families at loggerheads over use of the kitchen. There were shortages of everything, and suspicion. Among the presents we had taken (on advice) was tinned food; the bright coloured labels were removed – and burnt – almost as soon as we handed them over.

The second year we went, our car was followed almost everywhere, mostly by one or two motorbikes, even on tiny country roads. Mysterious individuals joined us at our hotel restaurant table, even when the place was virtually deserted, introducing themselves as just curious diners. We were delayed for more than three hours on the second return crossing, as the guards once again completely unpacked the boot and took out the seats, apparently suspecting that we would try to smuggle our friends out. That was the reality, not just of the Iron Curtain, but of divided Germany: human degradation and a total absence of social trust.

Given the depth of Germany’s east-west divide of the Cold War, however – the gulf in living standards, the isolation of the East from the wider world, and the increasingly divergent views of the past - it is perhaps more remarkable that Germany functions so convincingly now as one country.

I have been back to Stralsund several times since the Wall fell, and each time it has probably grown more like a modern version of the distinctive little cosmopolitan port that it had been when my father first visited. The colour and – some of – the energy are back. The combination of West German money, a respected Chancellor who grew up in the East - and not to be underestimated – a vast amount of popular political will has gone a long way towards remaking Germany as a single country.

If today’s Germans feel disappointment that the cracks between east and west are proving so hard to fill, they should remember how deep the divisions at all levels had become, and cheer up. On the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, any surprise should be not about the divisions that remain, but how well united Germany has worked out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments