Fall of the Berlin Wall: A people’s uprising that grew until it remade Europe

In a matter of months, a few local outbursts of protest set off a vast conflagration of people-power that overwhelmed the entire Soviet bloc. Steve Crawshaw remembers the exhilarating challenge of reporting the events for ‘The Independent’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Drama piled upon drama, all across eastern Europe. Repressive, seemingly permanent one-party systems crumbled within months, weeks, even days. In the annus mirabilis of 1989, Wordsworth’s words with reference to an earlier revolution seemed entirely appropriate: bliss was it in that dawn to be alive.

On 9 November, the Berlin Wall broke open. The barrier that divided a city and a continent had seemed eternal. It lasted just 28 years.

A week later, police violence in Czechoslovakia triggered what became known as the velvet revolution, in some ways the most magical of all the revolutions that year. At the beginning of November, dissident playwright Vaclav Havel had told me, in an interview for The Independent, that his country was a “pressure cooker”. Barely a fortnight later, the cooker exploded.

Few of my memories from that remarkable year are more vivid than standing in the midst of the vast crowds that filled Wenceslas Square in Prague. The protesters cheerfully jangled bells and keys. It was a reference to the traditional ending of Czech fairy tales: “The bell is ringing — the story is over.” After a week of protests, it was indeed all over. The hardline leadership resigned en masse on a Friday evening. Quiet Prague went wild. Barely a month later, the much-jailed Havel became his country’s president.

By year-end, ninepins had tumbled from the Baltic to the Black Sea. Even the brutal dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu in Romania collapsed. A pro-regime propaganda rally went badly wrong, leaving Ceausescu helplessly waving his arms as he was jeered on live TV. Endgame followed, within days.

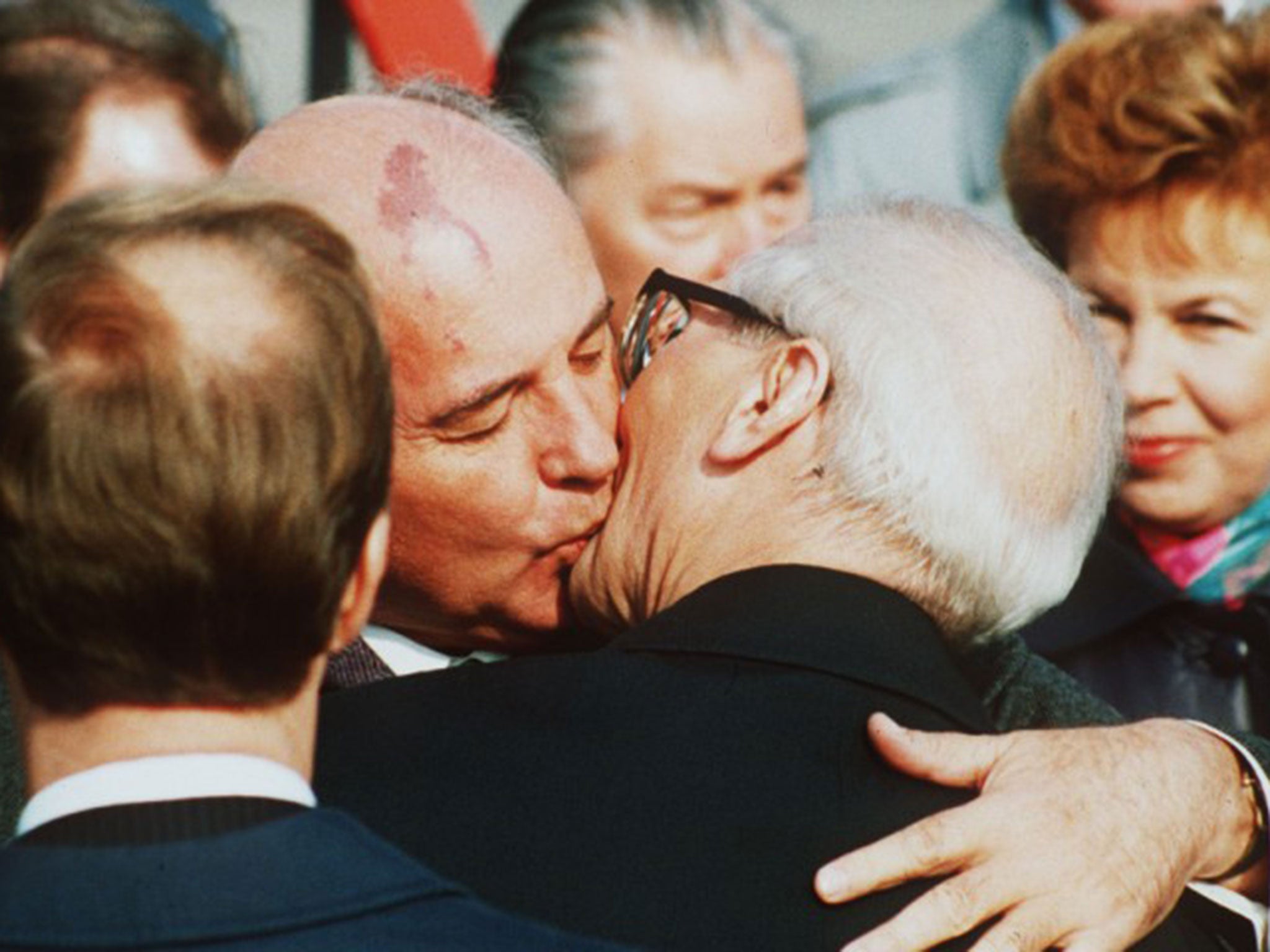

Mikhail Gorbachev, the reformist Soviet leader, reaped global praise for the democratic revolutions that engulfed the region – and with some reason. In contrast to Leonid Brezhnev, a recent predecessor in the Kremlin, he did not see tanks as the answer to every problem.

But the changes in eastern Europe did not begin with Gorbachev, let alone with the fall of the Wall.

Nine years earlier, when the tank-loving Brezhnev was still in power and Gorbachev was a loyal party secretary in the sticks, I was living in Poland, and thus witnessed the unthinkable becoming real.

In August 1980, millions of Poles demanded the legalisation of Solidarity, an independent mass-membership organisation whose very existence challenged the one-party state. Previous protests had ended in bloodshed. Commentators around the world agreed: the strikers could never win. And yet, within weeks, the legalization of Solidarity was agreed. It was a de facto legal opposition in the heart of the Soviet bloc.

These achievements were never fully reversed, even when tanks went on the streets the following year. Brezhnev, busy with little local difficulties in Afghanistan, did not send Russian tanks into Poland, as he had done with Czechoslovakia in 1968. He subcontracted the task to the Polish Communist leader, General Wojciech Jaruzelski. But the protests didn’t stop. Finally, after seven restless years, Poland’s rulers accepted they had no option but to talk.

In June 1989, a re-legalized Solidarity won partly free elections by an overwhelming margin. In the Senate, they gained a faintly absurd 99 out of 100 freely elected seats. When I interviewed Jaruzelski a few days later, he admitted the Communists might now lose power. Sure enough – and despite grinding of teeth in Moscow — Poland gained a non-Communist prime minister in August. The appointment of Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a Solidarity intellectual who had spent time in jail, broke every rule of the Cold War status quo.

Poland thus paved the way. But Poland was not the only place where epoch-making dramas took place long before the Wall came down, mostly out of sight of the world’s cameras.

As a student, I had lived in the Soviet Union in the 1970s. At that time, we all knew that the essentials would never change. By early 1989, however, the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were shattering all taboos. They talked about regaining the independence which Stalin had destroyed as part of his secret deal with Hitler half a century earlier – a deal whose existence the Kremlin still refused even to admit.

The Balts explained, in one conversation after another, why the collapse of the Soviet empire was now inevitable. But what if the tanks come in? I asked an Estonian professor, in astonishment. That would be the final act of the “dying colossus”, she said. (She and her colleagues were right: when Gorbachev’s troops killed 13 peaceful protesters in Lithuania two years later, the crackdown accelerated the collapse of the Soviet Union itself.)

In Hungary, too, huge changes were under way by spring 1989. Former prime minister Imre Nagy – executed, after the 1956 uprising — was given a state reburial. The authorities started talking about multi-party elections. On 2 May, they even cut a piece of symbolic barbed wire at the border, thus chopping a literal hole in the Iron Curtain – with unexpected consequences.

By early autumn, the pressures for change in Poland, Hungary and the Baltic states had spread to East Germany, too. “We’re staying here!”, chanted the crowds, unnerving the authorities even more than the hundreds of thousands who had already left via Hungary’s newly open borders.

Most dramatically, ahead of a planned protest in Leipzig on 9 October, the East German authorities threatened a Tiananmen-style massacre, promising to “end these counter-revolutionary actions once and for all – if need be, with weapons in our hands”. And yet, tens of thousands came out that day – more than ever before.

Their mass courage forced a political handbrake turn. Hospital beds had been cleared in expectation of casualties. But there was nothing. As we walked, there was no gunfire. There were not even any arrests or beatings, unlike on all previous occasions. Fear gave way to euphoria. It was a humiliating climbdown for the regime; that night, the Stasi secret police threw me out of Leipzig for the crime of witnessing and reporting on such a giant retreat.

In the weeks to come, a series of dramatic concessions followed, the most surreal of which came on 3 November. All East Germans were permitted to leave for the West, with the caveat that they must make a brief detour via Czechoslovak territory in order to get there. Evidently, there was only one more card to play – knocking a hole in the Wall itself.

As I wrote from Prague that night: “It is difficult to see the latest retreat by the East German leadership as anything other than the beginning of the end for the East Berlin regime – and perhaps the beginning of the end for East Germany itself.”

The fall of the Wall took the world’s politicians by surprise. (“Are you sure?”, Chancellor Helmut Kohl asked his adviser when he heard the news.) But that was because the politicians believed that only their fellow-politicians mattered. They underestimated what Vaclav Havel, a decade earlier, had described as “the power of the powerless”.

On 6 November, Andreas Whittam Smith, The Independent’s founding editor, took the idea seriously enough to order a two-page “obituary” of the Wall, to be prepared in advance and dropped into the paper at short notice. The executive charged with commissioning articles asked me how much time I thought we had before it would be needed. I had little idea, beyond “Very soon – maybe two weeks?”

That conversation was on Monday. The Wall broke open on Thursday evening, in bizarre circumstances which famously included a memo about new border regulations, read out by mistake in the confusion of a government press conference. We scrambled to catch up, like everybody else.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and other miracles of 1989 were an unintended consequence of the more limited revolution Gorbachev wanted to unleash. With his much heralded perestroika and glasnost – economic restructuring and fewer lies, the twins of reform – he sought improved efficiency.

But things went much further than he had ever dreamed. Gorbachev did not control the direction of events. But without him in power, the end might have been much bloodier, and that is an important difference.

In 2014, there are interesting echoes of 1980 and 1989. When protesters in Hong Kong demanded basic rights in recent weeks, Margaret Thatcher’s former adviser, Charles Powell, grandly informed them that their demands were “unrealistic”, and that they should be grateful for what they have got. Stay at home, was his message.

Nobody knows what will happen next, in Hong Kong or China. But it is worth remembering: in 1980, the Poles who risked their lives were also told they were “unrealistic”; so were the Balts, in 1989.

Clearly there are many differences between east Europe in 1989 and China today. But some of the same choices face today’s leaders in Beijing as faced the ultimately pragmatic Gorbachev 25 years ago. Violence is never the way forward.

Before Solidarity existed, the Polish poet Stanislaw Baranczak wrote a poem called “Those men, so powerful”. It was published in Index on Censorship magazine in 1978. The now-battered issue still sits on my shelf.

Baranczak’s poem, about loss of fear, concluded that the all-powerful ones are, in reality, “the ones who are afraid the most.” And that was the real message of 1989 – a message that may again prove relevant, in the months and years to come.

Steve Crawshaw, Director of the Office of the Secretary General at Amnesty International, was 'The Independent’s' Russia and East Europe Editor from 1988 to 1992

Tomorrow: More Berlin Wall memories, including Tony Patterson on the fall of Honecker; and an East Berliner’s tale of the day lessons ground to a halt

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments