Deborah Sampson: ‘The first woman to take a bullet for her country’

She stitched herself a uniform and posed as a man for 17 months in the Continental Army. But is Deborah Sampson’s account completely accurate?

Hers has always been one of the more astonishing, if little-known, tales of the American Revolution: a woman who stitched herself a uniform, posed as a man and served at least 17 months in an elite unit of the Continental Army. Wounded at least twice, Deborah Sampson carried a musket ball inside her till the day she died in 1827.

While historians agree that Sampson served in uniform and spilled blood for her country, gaps in the account have long led some to wonder whether her tale had been romanticized and embellished – possibly even by her.

Did she fight in the decisive Battle of Yorktown, as she later insisted on multiple occasions? And how did she keep her secret for the many months she served in Washington’s light infantry?

Now, scholars say the discovery of a long-forgotten diary, recorded more than 200 years ago by a Massachusetts neighbour of Sampson, is addressing some of the questions and sharpening our understanding of one of the few women to take on a combat role during the Revolution.

“Deb Sampson, her story is mostly lost to history,” says Dr Philip Mead, the chief historian and director of curatorial affairs of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia. “So, finding a little piece of it is even more important than finding another piece of George Washington’s history.”

The museum bought the diary for an undisclosed sum after Mead spotted it at a New Hampshire antiques show last summer. He plans to showcase it next year with other items about the role American women played in the Revolution, as part of a larger celebration of the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment.

The skeletal facts of Sampson’s military service have long been known. After at least one failed attempt to enlist, she ultimately succeeded in joining and fighting with a Massachusetts company that saw action in the Hudson Valley. Her secret went undiscovered until 1783, when, just months before the war’s end, she fell sick in Philadelphia and was found out by a doctor. There was no reprimand, just an honourable discharge.

Untangling the fuller story has been more complicated. She left only a smattering of records in her own words and seems to have exaggerated her exploits at the urging of Herman Mann, a sensationalist newspaper publisher. He took liberty with the facts in memoirs he ghostwrote for her in 1797, and had a hand in a florid speech she delivered during a paid lecture tour of New England. Each performance included a moment when she theatrically switched out of her dress and reappeared in light infantry garb.

Sampson “is a challenging figure’’, says Harvard Professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, an expert on forgotten women, “because she recreated herself so many times – and then was recreated again by her supposed biographer.”

As recently as 2016, Meryl Streep recast history a bit while praising Sampson as a model of “grit and grace” at the Democratic National Convention. She referred to Sampson as “the first woman to take a bullet for her country”. That designation more properly belongs to New York’s Margaret Corbin, who never enlisted but continued to fire her husband’s cannon when he fell at Fort Washington in 1776.

The diary, written by Abner Weston, suggests Sampson likely did not fight at Yorktown as she claimed. He dates Sampson’s botched enlistment to a period around January 1782, months after the British thrashing at Yorktown.

“If you really want to put her at Yorktown, you could start stretching it, but that sounds like pretty strong evidence that she probably wasn’t there,’’ says Dr David Osborn, site manager of historic St. Paul’s Church in Mount Vernon, New York, a national park site that dates to the Revolution.

He notes, though, that Sampson would hardly be the first veteran to place herself at the scene of a prominent battle that might be more familiar to folks back home.

Weston, who served as corporal in the Massachusetts militia, created at least three diaries that chronicle the war years, including his deployment to help defend Rhode Island in 1780 and to reinforce West Point in 1781. Two of the diaries are already held by the National Archives.

The third diary that just resurfaced is a hand-stitched, 68-page account of the period between 28 March 1781, and 16 August 1782, which Weston updated while back home in Middleborough, Massachusetts, where Sampson also lived.

In an entry for 23 January 1782, Weston, then 21, wrote with variant spelling about an “uncommon affair” that rocked the town. A woman, posing as a man, had tried to enlist.

Deb Sampson, her story is mostly lost to history; finding a little piece of it is even more important than finding another piece of George Washington’s history

“Their happened a uncommon affair at this time,” he wrote, “for Deborah Samson of this town dress herself in men’s clothes and hire herself to Israel Wood to go into the three years Servis. But being found out returned the hire and paid the Damages”.

Sampson’s motivation for enlisting has never been clear. Unabashed patriotism? Financial distress?

In the last years of the war, towns that struggled to fill their quotas of recruits offered bounties to attract volunteers. Sampson, born to an indigent family in Plympton, Massachusetts, around 1760, certainly might have needed the money. She had previously worked as an indentured servant.

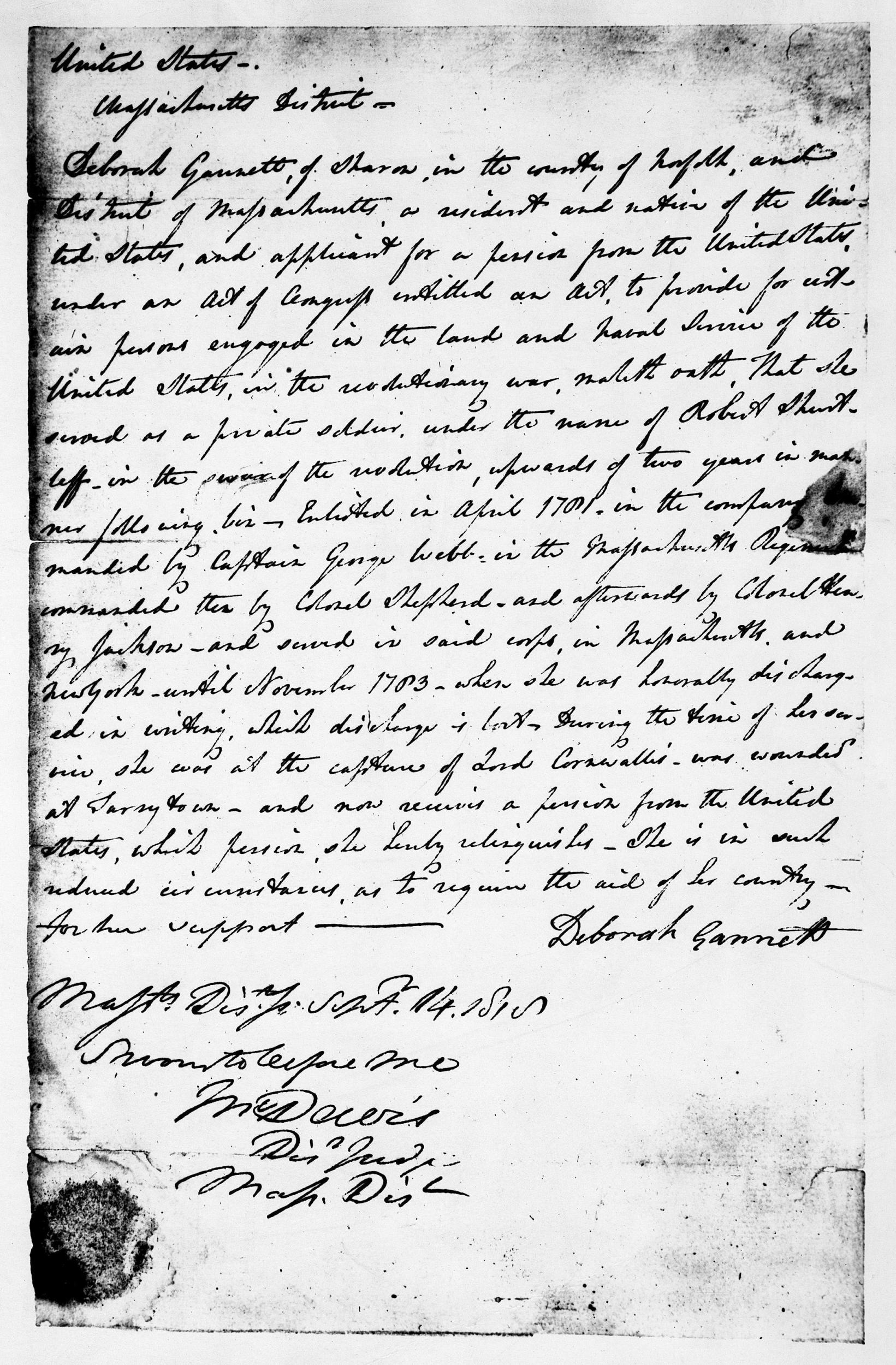

What’s clear, according to evidence in the Massachusetts Archives, is that later that year she tried to enlist again, 40 miles away in Bellingham, Massachusetts. This time her gambit worked, and in May 1782 she accepted a bounty to suit up in place of folks from Uxbridge, one town over. She called herself Robert Shurtleff, her alias for the rest of the war.

Dressing as a man was considered a crime in Massachusetts at the time, and Sampson’s audacity later invited the wrath of the Baptist Church. In September 1782, while she, long gone, served with her unit under an assumed name, church elders, still reeling from her earlier attempt to enlist, excommunicated her, citing her for “dressing in men’s cloths and enlisting” and other conduct they considered “loose and unChristian like”.

After the war, Sampson married a Massachusetts farmer, raised a family and spent a lot of time fighting congress to get back pay for her wartime service. Paul Revere and John Hancock both helped her in that partially successful effort.

The museum’s discovery of the diary also ended well. The document had turned up among miscellaneous papers purchased en masse by DeWolfe & Wood Booksellers in Alfred, Maine, last year. One of the owners, Frank P Wood, later brought it with him to read at the New Hampshire Antiques Show, which Mead attended while on vacation.

The two men got to talking. Mead, who had studied Weston’s other diaries as part of his doctoral work at Harvard, mentioned his new role at the museum. Wood whipped out the diary to get his visitor’s take. Soon they had a deal.

Ken Burns, the filmmaker who is creating a documentary about the American Revolution, says he might feature Sampson in the work, and the fact that the diary undermines her account of serving at Yorktown does not affect the overall impact of her story.

“She clearly bled for the cause,” he adds. “It becomes super important that we don’t impose modern sensibilities on what this speaks.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks