Syria’s revolution does not belong to the fighters alone – but to the activists who never gave up

For more than 13 years, Syrians inside and outside of the country have been part of the revolution to remove Bashar al-Assad from power. Richard Hall reports

There’s more than one way to topple a dictator. While the fighters who marched on Damascus will receive most of the credit for removing Bashar al-Assad from power, thousands of Syrians did their part for years in the background without ever touching a gun.

They were doctors who worked under the bombs, researchers who documented war crimes, campaigners who lobbied in exile for international support, young Syrians who gave up their jobs abroad to return home and become citizen journalists, and refugees spread around the world who worked to help other refugees like them.

They all contributed in their own way to the revolution that brought down Assad.

The doctor

Zaher Sahloul, a Syrian-American doctor who emigrated to the US in 1989, began crossing into Syria from the first days of the war to help treat those in need.

He went on more than 25 medical missions to the country, operating under relentless bombing by Assad’s jets in Aleppo, Homs and Hama to help set up hospitals and train medical staff. On his first trip, in 2012, he was fired at by Turkish soldiers while sneaking across the border with a group of smugglers.

“I never imagined in my life that I was going to end up working with smugglers, walking in the mountains and forests in the middle of the night to cross the border,” he says. “I escaped death many times.”

Dr Sahloul’s missions to Syria served a desperate need: Assad’s jets were bombing hospitals and medical facilities across rebel-held areas, leaving millions without any access to care. Medical facilities needed outside help to keep functioning. Dr Sahloul’s organization, the Syrian America Medical Society, stepped in.

“I worked in hospitals that were shelled multiple times during the siege of Aleppo. I worked in hospitals that were built underground and in caves because they were bombed multiple times,” Dr Sahloul tells The Independent.

But like many Syrians in the diaspora, Dr Sahloul took on another role. After returning from each trip, he met with members of Congress, with Samantha Power more than a dozen times when she was a National Security advisor, wrote op-eds in the press, and testified at Congressional hearings and at the United Nations.

“Every time I would bring them insights from the field. There was such a disconnect between what was going on in the field in Syria and what reached policymakers. And the crisis kept changing, so it was important to bring them these stories,” he says.

Dr Sahoul says the Syrian diaspora played a “major role” in influencing events in Syria for the better over the last 13 years, and will do so in the years to come.

“You have an estimated 20 million Syrian diaspora in different countries. But let’s say that you have three or four million who left Syria in the last 13 years and ended up in the United States and Europe and other states. They established organizations, connected with their policymakers, did all kinds of stuff that is not reported, and I think they will be a great player in what is to come,” he says.

The writer

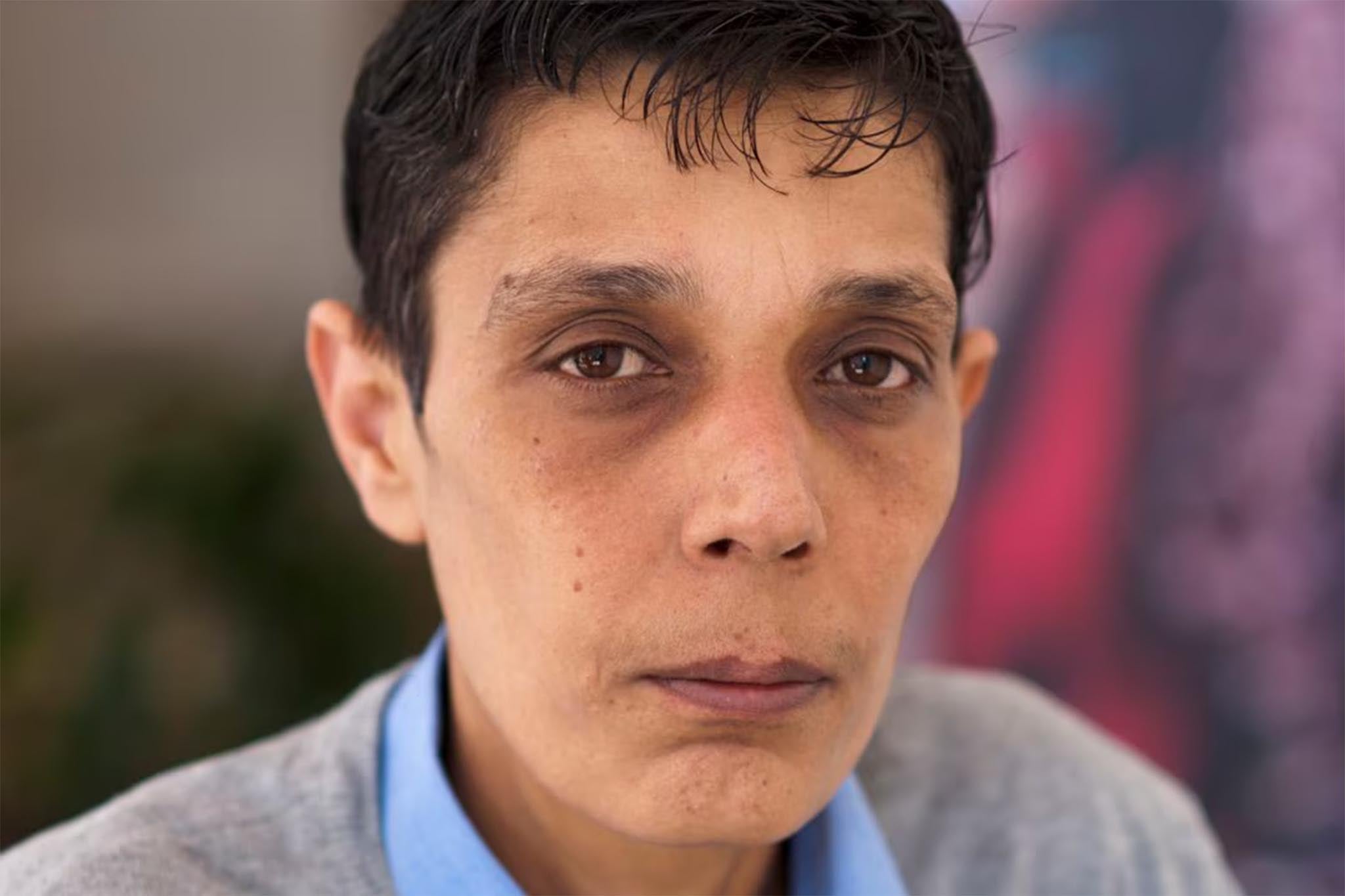

Loubna Mrie was in her early twenties when the protests began in 2011. She hails from the Alawite community to which Assad belongs, and most of her friends and family opposed the demonstrations. But the images of brutal crackdowns moved her to join them.

She did anything she could to help — even ferrying medicine and supplies to the frontlines and helping displaced people find homes. Eventually, she found her calling in photography.

“I was a firm believer that if we document atrocities, we can stop them. I felt that the world was not stepping in because they didn’t know. That was what drove us,” she says.

She took pictures of the demonstrations, the crackdowns, and of the war that followed, and sent them out into the world. She was picked up by Reuters and worked for the agency in Aleppo.

“In Syria, we didn’t have free journalism. But I could see something, and I could film something, and then I could upload it to a Facebook page where 1000s of people would see it, it felt so powerful,” she says.

It’s very important to remind the world that this effort is not just for the fighters. We held these people accountable, and we will hold these people accountable if they start to f*** up

When the atrocities mounted and the world still did not intervene to stop Assad, she began to lose hope.

She left Syria for Turkey and then eventually to the US in 2014 on a photography scholarship. She thought she could hone her craft away from the war, but being in exile tore her apart. Her mother was killed during her time away.

“I lost my family, I lost all my friends back home. And I was looking for a sense of belonging again. It was very hard to be part in Syria and part here,” she says from New York, where she now lives.

Mrie soon realized that photography for photography’s sake was not what she wanted to do. She felt power in her work in Syria because she was working for the greater good — she was helping her country.

“I shifted completely to writing. Part of it was also healing — writing was very healing,” she says.

“I felt it was really important to have a Syrian writer who was born and raised in Syria, and joined the uprising, to write for the English-speaking audience. I started to realize how the discourse about Syria in the West was mainly from a geopolitical lens and it felt like we as individuals were not taken into consideration,” she adds.

Mrie became a prolific writer on Syrian affairs, bringing a much-needed perspective to the debates about how to solve and understand the crisis.

After years of working inside and outside of Syria, she has watched the fall of the Assad regime in the past week in a state of disbelief.

“It feels great to know that we were not crazy to dream this big. At so many points in my life, I wondered if we were being naive to think that we could overthrow one of the worst governments the world has seen. And the answer is, no. We had every right to overthrow this government and to dream of a better future,” she says.

Mrie believes that the work of Syrian activists is only just beginning.

“It’s very important to remind the world that this effort is not just for the fighters,” she says. “We held these people accountable, and we will hold these people accountable if they start to f*** up.”

“Because one thing this uprising taught us is that fighting the same enemy does not mean we are fighting for this for the same reasons. And it will fall on us journalists, on lawyers, on future politicians, to make sure they don’t intimidate anyone with their arms.”

The teacher

Telling the outside world what was happening in Syria became Wissam Zarqa’s mission in the darkest days of the war. During the siege of Aleppo by Russian and Syrian government forces — when no food was allowed in and bombs rained down on the rebel-held eastern part of the city every day — he remained to document what was happening.

Zarqa was an English teacher and set up a school in 2015 to teach children in the city who had missed years of education because of the war. With another teacher, he created a WhatsApp group to share daily updates from the besieged city with journalists. He would send long voice notes describing the hunger and the desperation of the people stuck there, while the sound of bombs falling could be heard in the background. When he and his family were able to get food, he would share pictures of his meals.

“I didn’t see myself as a journalist or an activist, I was just a teacher living in besieged Aleppo, talking about his life, his students’ life, people around him,” he tells The Independent.

“I didn’t know what to do, but I wanted to do something,” he adds.

At the time, foreign journalists were not able to access Aleppo, so messages from people like Zarqa became crucial in helping the world know what was happening in the city. His name and his testimony would appear in news stories from media outlets around the world.

“We just thought, if we speak more, less people will die,” he tells The Independent. “Later, we weren’t sure if journalists could change anything.”

Zarqa shared his stories at great personal risk. The city was at risk of being captured all the time and Assad’s forces would arrest anyone associated with anti-government activism. Nevertheless, he stayed in east Aleppo until the very end, when the last remaining residents and fighters were bussed out of the city and on to Idlib.

“It feels like a dream. But we’re still worried about the thugs he left behind,” he says.

Today, Zarqa lives in Idlib and hopes to return home now that Assad is gone. But his home in Aleppo is in a part of the city that is controlled by Kurdish forces not aligned with the fighters who took Damascus.

“It’s funny that Bashar’s palace was liberated but my home is not liberated yet,” he says. “But going back to Aleppo is a matter of time.”

The lawyer

Many other Syrians spent the best part of the last 13 years documenting the horrors of the war. In 2011, when anti-Assad protests broke out, lawyer Fadel Abdul Ghany founded the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), a UK-based independent organization that monitors and documents human rights violations in Syria.

“We didn’t have much experience at the beginning, but we grew up day by day,” Ghany says.

“We wanted to preserve the violations and to document them based on human rights methodology and protocol,” he says.

A big part of the group’s work was documenting every death in the conflict. With a network of sources on the ground and a team monitoring open-source information, the SNHR built a database of casualty figures even as the conflict became so deadly that even the United Nations stopped counting.

“Our work is very hard. It’s mainly casualties, death, torture, displacement, attacks against hospitals, schools, arbitrary detention and arrest, forced disappearances, and chemical weapons attacks. We’ve been through numerous atrocities and we covered all of them,” he says.

Ghany’s team would interview witnesses of these atrocities to document them and ensure they were not lost in the fog of war. Their reports were used by other human rights groups, the UN and the US State Department.

Ghany saw the work as invaluable for ensuring accountability when the war was over.

“I think what we did was huge work, difficult, terrible, but our people deserved it,” he says.

But he insists his work is not over.

“Our role as a human rights org is to keep monitoring what the authorities will do, how they will behave, what they will do, will they respect human rights, and we are monitoring from day one what those new authorities will do,” he says of the rebel groups that toppled Assad.

“There is a huge role for us to play in the post-conflict period,” he adds.

The activist

There were many who didn’t live to see Assad’s eventual downfall. Mazen al-Hamada, one of Syria’s most prominent activists, was one of them.

Hamada was from the eastern city of Deir ez-Zor. He joined the first anti-government protests that erupted 2011 and was arrested several times by the Assad regime.

In 2012, he was caught by Assad’s forces while smuggling baby formula to a Damascus suburb – which was then under siege by the Syrian army. Hamada endured unimaginable physical and sexual assaults during his detention.

When he was released in 2014, he sought asylum in the Netherlands, where he became an advocate for thousands who had disappeared into Assad’s dungeons and spoke publicly about the torture he endured there.

Hamada returned to Syria from Germany in 2020 after being promised amnesty by the Syrian regime. He was arrested and never heard from again.

When rebel fighters stormed Damascus and liberated the notorious Saydnaya prison this week, his body was found among the dead. His friends believe he was killed in the last few days of the Assad regime.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks