The Big Question: What are the consequences if Nato expands further to the east?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

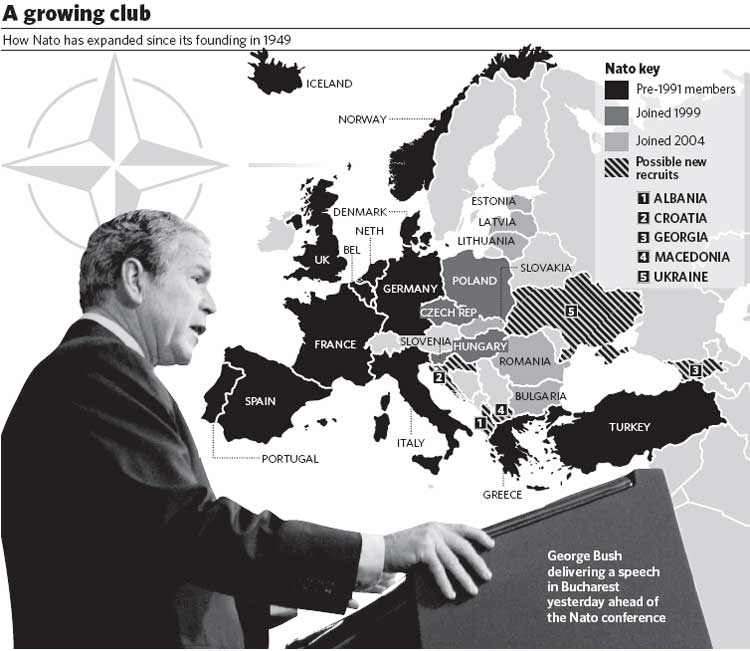

Leaders of the 26 countries that make up the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation assembled last night in the Romanian capital, Bucharest, for their 2008 summit, which is being described as potentially one of the most significant in Nato's 59-year history. The meeting ends at lunch-time tomorrow, following separate meetings with President Yushchenko of Ukraine and President Putin of Russia – the first time that a Russian leader has been invited to a Nato summit.

Why is Bucharest the venue?

Romania became a full member of the alliance in the most recent round of enlargement, in 2004, along with the Baltic States, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Slovenia. As an organisation, Nato has made a practice of holding summits and ministerial meetings in the capitals of the newest members; the last summit – in 2006 – was held in the Latvian capital, Riga.

What makes this summit different?

The alliance is facing the greatest stresses and strains for many years, and every agenda item at Bucharest will reflect them. Initially, it had been envisaged that the most contentious issue would be Afghanistan. Nato is on the back foot here. The Taliban has started to reassert itself, the opium poppy harvest is at its highest for years, and a Nato mission that had been conceived as post-war reconstruction and development now entails regular combat, at least in the south of the country. The US came close to an open rift with Germany over its apparent unwillingness to contribute more troops and accept deployments outside the more peaceful north. But other governments, too, have qualms about sending troops to Afghanistan, or increasing their contingents, because of public opposition at home.

Will Afghanistan be the only dispute?

Not only will it not be the only dispute, but it may well not be the most divisive. During his recent state visit to London, President Sarkozy of France offered to send another 1,000 French troops to Afghanistan. He got into trouble with his Socialist opposition for announcing the decision abroad, rather than to his own Parliament, but the offer has helped defuse tensions in Bucharest.

It now seems that plans for future enlargement will move into the "most contentious" slot. George Bush has made no secret of his desire to see Ukraine and Georgia admitted to the first stage of membership consideration at this summit. His visit to Kiev on the eve of the summit was designed to send precisely this message. Britain seems to share Mr Bush's enthusiasm, but has kept rather quiet about it.

By no means all Nato members share Mr Bush's ambition, however. France and Germany both have misgivings. On the one hand they fear more dilution of Nato's strength if it expands too fast. On the other, they worry that admitting Ukraine, in particular, will needlessly complicate relations with Russia. A secondary issue – at least for Nato – is strong opposition within Ukraine to joining Nato.

Will the enlargement quarrel turn into a US-Europe split?

Both disputes – about troop levels in Afghanistan, and enlargement – carry more than a hint of divergent priorities in the US and Europe. They expose different attitudes to defence spending and risk, and Europe's often less ideological approach. Enlargement, for instance, is seen in terms of practicalities, rather than any sweeping vision for "the West".

But there are also divisions within Europe, reminiscent of the old-new Europe split over Iraq. Chief among them is the US plan to station anti-missile installations in Poland and the Czech Republic as part of its missile defence programme. So far, the US has negotiated with these countries bilaterally, which kept Nato out of the picture.

For the US to have bilateral agreements on defence installations in Europe outside the framework of Nato, however, cannot but cast doubt on the usefulness and coherence of the alliance. The US anti-missile plans also infuriate the Russians, which see them – despite fervent US denials – as directed primarily against them.

So where, if at all, can the allies agree?

Croatia and Albania have also put themselves forward for Nato membership, and their applications are likely to go foward unopposed. The former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia also wants to get on the first rung of the ladder. Greece could veto this – not for any major geo-strategic reason, but because it wants Macedonia to change its name so as to clarify that it has no designs on Greek Macedonia. Compared with the complications associated with admitting Ukraine and Georgia, this looks a mere detail.

Any more light on the horizon?

A little. M Sarkozy has said that he wants France to rejoin Nato's military command structure, after a break of 40 years. This could strengthen Nato and make it more cohesive. But the US and Britain have seemed less ecstatic at the prospect than might have been expected, suspecting perhaps that M Sarkozy sees greater French involvement as a way of reinforcing the European "pillar" of Nato with a view, in time, to establishing more EU autonomy in defence.

If, as it appears, the division of Cyprus may be nearing a solution, then a major point of friction between Turkey and Greece would be removed – something else that could foster greater unity within the alliance.

Why is Russia so exercised by Nato?

It sees Nato as a Cold War alliance whose main purpose is to contain Russia. The way so many former Soviet bloc countries and republics sought – and were given – Nato defence guarantees only reinforces Russia in that view. Moscow also claims that Nato has broken undertakings about not expanding to the Russian border and not placing installations in the vicinity.

In an ideal world, perhaps, Nato would have declared victory when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and ceremonially dissolved itself. A new alliance, with a new brief, might have pre-empted some of Russia's subsequent objections. At the time, though, Western leaders had more pressing concerns, and East and Central Europeans were clamouring to join. Nato survived, albeit with a changing – and much broader – remit.

Nato set up the Nato-Russia Council to try to normalise relations. But the mechanism has never dispelled the many mutual suspicions. This body will meet tomorrow morning, with Putin in attendance – a sign perhaps that both sides recognise the dangers and want, if possible, to find common ground.

Does Nato still have a role?

Yes...

*It is the world's most advanced, most efficient and most admired military alliance

*It gives the newly independent countries of East and Central Europe a sense of confidence in their security

*It has transformed itself surprisingly quickly from a Cold War alliance into a potentially indispensable global player

No...

*It was a creature of the Cold War and should have been allowed to die with it

*Its planning structures and hardware are all geared to a set of military scenarios that no longer exist

*Its steady eastward expansion has made it into a huge liability for good relations between the West and Russia

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments