Ethical shopping: The Red Revolution

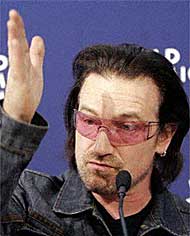

Irish rock star Bono has persuaded some of the world's biggest companies to back his new weapon in the fight against poverty: a consumer brand with a conscience. Cahal Milmo reports

From John Paul II to George W Bush, few have escaped Bono's campaign to charm and bully the world's powerbrokers into lending their support to his fight against global poverty and disease. Such has been the success of the Irish rock star's assault on A-list opinion-formers, ranging from Kofi Annan, the UN secretary general, to the billionaire currency dealer George Soros, that he was touted last year as a serious candidate for the presidency of the World Bank.

But now the U2 frontman with a taste for wrap-around shades, turned voice of global conscience, set his sights on an altogether more intractable constituency, the developed world's hard-boiled, price-conscious consumers and the conglomerates that seek their cash.

After more than two decades of berating world leaders on debt relief and economic justice, Bono yesterday unveiled his latest solution to the world's ills, climbing into bed with big business to sell branded sunglasses, trainers, T-shirts and the odd credit card.

Surrounded by senior executives from four multibillion-pound companies, the ethical troubadour from Dublin launched Product Red, his new brand that will raise funds to fight Aids, tuberculosis and malaria by harnessing the allure of the world's biggest consumer names.

American Express, Gap, Giorgio Armani and Converse, part of Nike, were unveiled as the first companies who have agreed to develop the "must-have" products that will be sold under the Red brand and donate a share of the profits to charity.

The initiative, which will be initially largely targeted at British shoppers, represents the latest development in the rise of "conscience consumerism" which has led to a boom in products from guilt-free bananas to gifts of livestock to be sent to the developing world.

A report last month by the Co-operative Bank estimated that British consumers spent £25bn on ethical goods and services in 2005, a rise of 15 per cent on 2003.

In a sign that repeated revelations about the sweatshop economics of parts of the global clothing industry are having an effect, the strongest growth area was in ethically produced garments. Demand for clothes produced with organic cotton or without heavy metal dyes rose by 30 per cent in the past 12 months, creating a market worth £43m.

But Bono and Product Red, which will use marketing expertise from executives in its partner companies, are anxious to put clear water between their collaboration with "iconic brands" and conventional charitable enterprise.

Money generated by the scheme will be donated to the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, which is pledged to spend more than £2.3bn in the developing world by 2007.

Bono, speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Swiss village and citadel of global commerce hitherto vilified by campaigners as a talking shop to shore up the developed world's trade dominance, said his new project was driven by hard-headed business principles rather than by philanthropy.

Brandishing the new American Express Red Card, the 45-year-old singer said: "Philanthropy is like hippy music, holding hands. Red is more like punk rock, hip-hop; this should feel like hard commerce." He added: "People see a world out of whack. They see the greatest health crisis in 600 years and they want to do the right thing, but they're not sure what that is. Red is about doing what you enjoy and doing good at the same time."

Starting on 1 March, consumers will begin to notice the first offerings from Red begin to trickle into the British high street and American shopping malls.

The initial clothing range will consist of wraparound Armani sunglasses, similar to those worn by Bono; a Gap clothing range to be launched next month in Britain with a T-shirt made in Lesotho; and Converse training shoes made from African mudcloth.

American Express is also launching its Red credit card, which carries the statement, "This card is designed to eliminate HIV in Africa", in Britain next month with a pledge to donate 1 per cent of the annual monthly spend on each card to the Global Fund.

The products are aimed at what Bono and Amex describe as "conscience consumers", the sector of affluent, educated spenders who are more likely to be influenced by the heartfelt proselytising of a rock star than slick television adverts and marketing campaigns. Amex believes the number of conscience consumers in Britain will grow from its present level of 1.5 million to more than four million by 2009.

The U2 singer, who played with Live Aid in 1985 before rising to prominence as an advocate for debt relief, on stages from the White House to the Labour Party conference, said: "I'm calling it conscious commerce for people who are awake, people who think about their spending power and say, 'I've got two pairs of jeans I can buy. One I know is made in Africa and is going to make a difference and the other isn't. What am I going to buy'?"

But while the benefits for large-scale corporations from Red may be clear, the partnership between such a prominent campaigner for equitable trade and action to tackle issues from debt to disease, and "big business" is generating queasiness among some leading charities.

That is because each of the partner companies will return a share of the profits from the sale of Red products to the Global Fund in return for the opportunity to increase their own revenue - and profits - by attracting ethical consumers. It is hoped that eventually hundreds of companies could be marketing Red products, creating a long-term source of income for charities worth "hundreds of millions".

But a senior policy official at one prominent British-based charity, which has hitherto supported Bono's campaign, said: "You have to admire Bono's creativity but there is a risk that this will ultimately alienate consumers and supporters. Unless it is very clear that a generous portion of what they spend on this T-shirt or pair of shades is going to fight Aids or malaria, then they are going to feel they are pouring money into the coffers of corporations who are getting the kudos of fighting poverty at a bargain price."

But organisers of Product Red said there was nothing wrong with encouraging corporations to lend their marketing expertise to the battle against diseases such as Aids in return for the chance to improve their profits.

Less than 1 per cent of the income received by Global Fund, whose supporters include the Microsoft multi-billionaire Bill Gates, comes from private corporate sources, rather than individual donations.

Bobby Shriver, the chief executive of Product Red, said: "We sought out iconic companies who make iconic products. Red partners expect they will broaden their own customer base and increase loyalty in a manner that delivers a sustainable revenue stream to both the company and the Global Fund."

The founder of the brand - standing shoulder to shoulder with his new corporate partners, including Giorgio Armani himself - admitted that some in the anti-poverty movement may not be comfortable with his scheme. But Bono said that in a climate where each day brings 6,500 HIV-related deaths in Africa, and 9,000 new infections, hard choices had to be made.

"Some people will be very upset," he added. "We're working with big business. But the problem just has to be sorted and we can't do it with governments alone. We're fighting a fire. The house is burning down. Let's get the water. You end up beside somebody who lives up the road who you don't really like. Do you care if he's polishing up his image by putting the fire out?"

Critics said the rock star and all but one of his backers were not helping their case by failing to state the proportion of the profits from Red products that will be sent to the Global Fund. American Express is so far the only participant to reveal its charitable arithmetic, pledging to donate 1 per cent of the monthly spend on its Red cards and 1.25 per cent of any spending above £5,000 a year. Even then, the company declined to say whether any of the 12.9 per cent APR charged in interest on outstanding balances will be donated to the charity.

None of the other participants were able to say what proportion of their profits from the Red range they expected to donate to the Global Fund, saying it was dependent on sales and the expansion of the brand to other companies and producers.

Armani, whose company intends to produce Red perfumes, watches, jewellery and clothing by the end of this year, said: "An ordinary person can simply walk into a shop and feel they can participate in helping the needy by simply buying a perfume. And cynically, I would add, without us changing the price of the perfume."

The companies insisted their participation went further than contributing profits. Gap said it had provided expert knowledge of how to produce dyes and yarns suitable for Western markets to the manufacturer of its first Red T-shirt in Lesotho and intended to produce as much of their new range in Africa as possible.

Andrew Rolfe, head of the international arm of Gap, which will charge £14.50 for its first Red T-shirt, said that with Bono as its chief advocate, consumers should feel reassured the brand was not paying lip service to good causes to drive profit. He said: " People could be sceptical but this is about making a real contribution. With his record in this field, Bono would not be advocating this programme unless he felt we were doing the right thing."

But Bono admitted the success or failure of his brainchild depended on human nature on the high street. "If people are jaded or cynical or genuinely not interested, we fail. But we've tried. I think we've come up with a sexy, smart, savvy idea that will save people's lives."

How coffee crisis launched commerce with a conscience

The plight of Mexican coffee farmers in the late 1980s was to give rise to one of the most successful consumer brands of modern times. Faced with rapidly dwindling prices for their beans following the signing of the International Coffee Agreement that handed the market power to the giant buyers, the growers decided it was time to fight back.

With the help of charities such as Oxfam, Christian Aid, Cafod and the World Development Movement, the Fairtrade mark was born. The first product hit the shelves in 1994, a bar of Green & Black's Maya Gold chocolate, followed swiftly by Clipper Fairtrade tea and Cafedirect coffee. A consumer revolution was born. Overall ethical consumer market in the UK - including banking and "Fair Trade" products - was worth £25bn in 2003.

Since launching its first products, Fairtrade has persuaded everyone from supermarkets to MPs, charities and councils to stock its growing range. Garstang in Lancashire even became the world's first Fairtrade town. With growth averaging between 40 and 50 per cent a year, sales topped £140m in 2004. According to Barbara Crowther, however, Fairtrade's philosophy remains steadfastly anti-philanthropic. "Fairtrade is a specific system to make sure trade tries to reduce the imbalance between rich and poor. It is about creating a sustainable system of intervention, building wealth from the bottom up."

Send a Cow is a similar success story. Formed 18 years ago by 17 West Country farmers in response to the Ugandan milk crisis, who send their African counterparts an animal from their own herds, the charity has gone from strength to strength and spawned a rash of imitators. Many of its 40,000 supporters, who helped raise £4.8m to help farmers in nine African countries last year, have received their contribution as a gift.

Closer to home and more than a century earlier, the Co-operative Bank was formed in Manchester in 1872 as the financial arm of the Co-op Wholesale Society. It refuses to invest in unethical activities, most notably the arms trade.

Last year the amount of money put into UK ethical savings and investments broke through the £10bn barrier for the first time. Co-operative Financial Services (CFS) said the level of ethical investment rose 18 per cent to £10.6bn during 2004. A total of £5.5bn had been put into "socially responsible" funds and £5.1bn deposited in ethical banks and credit unions.

In December, Dame Anita Roddick cashed in her 18 per cent share of the ethical beauty company she founded with her husband in 1976; it was said to be worth £100m. During its heyday in the 1990s, the company was making £25m a year. Dame Anita said that she planned to give away half of her windfall.

Jonathan Brown

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks