A Clockwork Orange: Ultraviolence, Russian spies and fake news

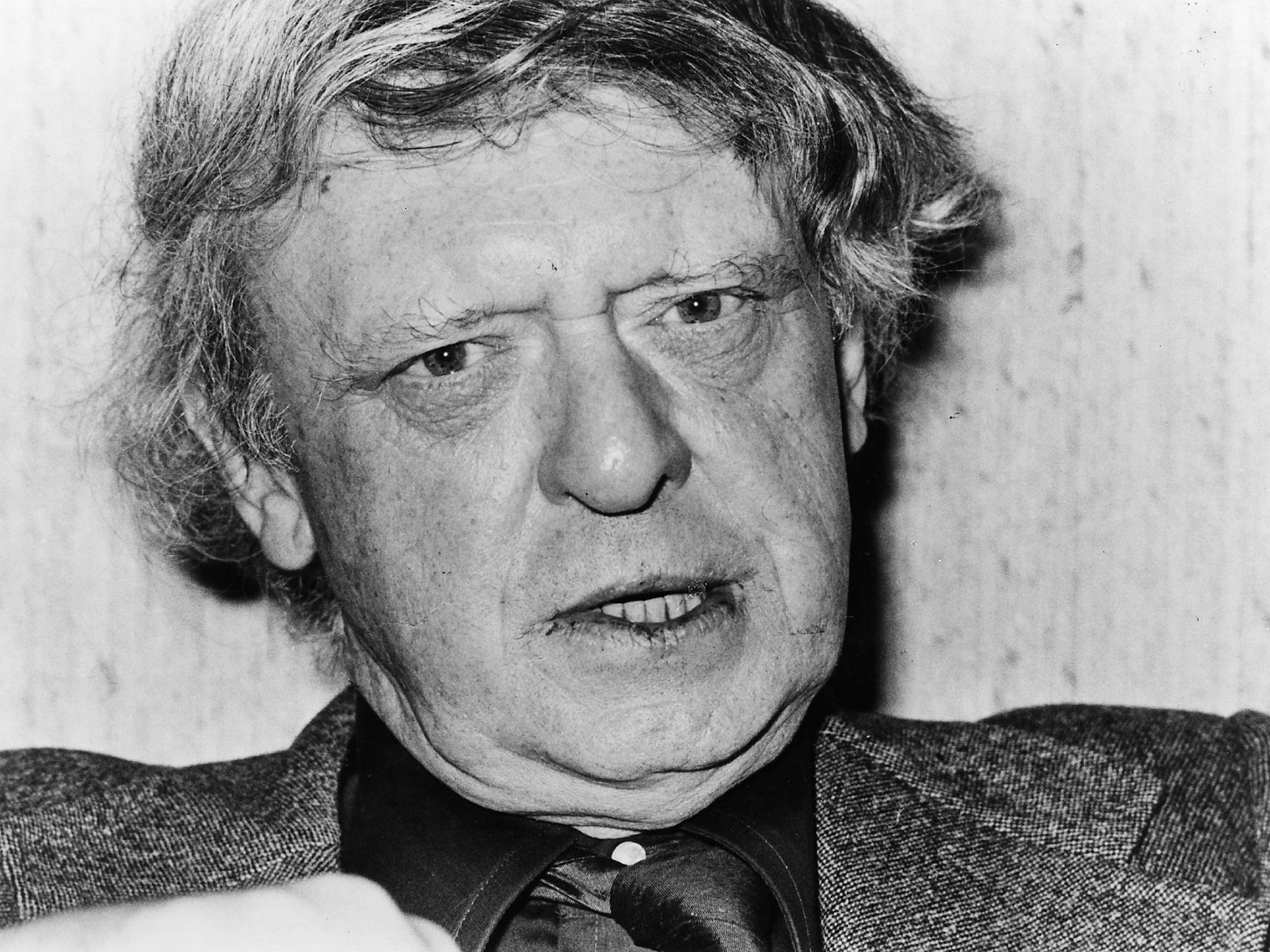

On the centenary of Anthony Burgess’s birth – A Clockwork Orange had a profound influence on the cultural and political landscape

The writer Anthony Burgess is most famous for his novel, A Clockwork Orange. This month marks the centenary of the writer’s birth and his dystopian vision still casts a long shadow over popular culture. But what is perhaps more intriguing is how the book was once drawn into a world of Russian espionage, fake news and paranoia.

During his lifetime, Burgess wrote over 30 novels, 25 non-fiction books, three symphonies and countless other musical works. But 55 years after its publication, it’s still A Clockwork Orange which has the most enduring influence.

One of the more unusual examples of this influence was the novel’s appropriation by the espionage community. During the 1970s, the title supposedly became the codename for an alleged campaign to undermine the prime minister, Harold Wilson. Prompted, apparently, by fears that Wilson was a Soviet agent and that he’d been placed in office after the KGB had poisoned the previous Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell.

Elements within the British secret service are alleged to have bugged his staff’s phones, burgled their houses and instigated a campaign to spread false rumours about him through the media. All of this was intended as a precursor to a coup which would see the army seize Heathrow airport and Buckingham Palace and put an interim Prime Minister in place.

The symbolism of the use of this title – of a novel about state brainwashing and civil disorder – is inventive, to say the least. It also has a strange resonance today, where again there’s rampant speculation about the way fake news and the use of “kompromat” (compromising material) is being used to manipulate Donald Trump who some fear is under the control of the Russian secret service.

This story may appear as something of an outlier in the influence the book has had. But politics and culture have rubbed shoulders throughout its history.

Someone else who was greatly influenced by the book was David Bowie. In the early 1970s, he’d wanted to make a musical of another famous work of dystopian fiction, 1984, but George Orwell’s widow, Sonia, refused him the rights. Instead, he adapted his ideas into Diamond Dogs and created his own dystopian world: a broken society where “a disaffected youth … lived as gangs on roofs and … had the city to themselves”.

In the Britain of that time, with its food shortages, power cuts and IRA bombings, an artistic fascination with these ideas isn’t that surprising. The bleakness of the social landscape shared much of the mood and outlook of the post-war period in which Orwell was writing. But the world that Bowie ended up imagining arguably has as much to do with Burgess’s “world of adolescent violence and governmental retribution” depicted in A Clockwork Orange.

Coincidentally, Sonia Orwell also played a bit part in an incident which was formative in the inception of the novel. In 1944, when Burgess was stationed with the army in Gibraltar, it was Sonia Orwell who sent the letter informing him that his wife, Lynne, had been attacked in London by four GIs. Lynne suffered a miscarriage and it seems likely that the incident contributed to her later ill-health and early death.

Violence and catharsis

Not only does A Clockwork Orange explore a society overrun by random acts of recreational violence but Burgess also includes a scene in which an unnamed writer is attacked and forced to watch while his wife is raped. In his introduction to the novel, Blake Morrison suggests that writing this was a form of catharsis for Burgess – although later in his life Burgess spoke of the dejection he felt at the accusations that his artwork was some sort of promo glamorising violence.

Following a failed attempt by the Rolling Stones to film the novel and Andy Warhol’s highly experimental take on it, Stanley Kubrick’s celebrated adaptation came out in 1971. This further bolstered the cultural impact. Bowie, for example, borrowed from both its visual style and soundtrack for his live shows, while his fascination with Burgess’s invented language, Nadsat, was to continue right up until his final album Blackstar, which features a song mostly written in it.

In 1973 – around the same time as the Wilson plot was first being hatched – Kubrick withdrew his film version of the novel from British cinemas, following several high-profile cases of supposed copycat violence. For Burgess, the film had always been a mixed blessing. When the novel came out in America, his publishers decided to cut the final chapter, which shows the protagonist grown up and wishing to settle down and start a family. Instead, it ends with him unrepentant and returned to the psychotic mindset that he’d had prior to his brainwashing treatment. It was this version that Kubrick filmed.

Burgess felt this prevented the book from working properly as a novel, where moral growth is a part of the essence of narrative. He saw the decision as symptomatic of the politics of the times – his book was Kennedyan, he wrote, when what was wanted was something Nixonian, “with no shred of optimism in it”. He concluded: “America prefers the other, more violent, ending. Who am I to say America is wrong? It’s all a matter of choice.”

Philip Seargeant is a senior lecturer in applied linguistics at The Open University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks