A decade on, Ceausescu’s children were abandoned and forgotten

The problem of rebuilding Romania’s notorious orphanages after conditions were revealed in the 1990s proved insurmountable. It was families that the lost children needed, says Cole Moreton

Ion is 10-years-old. He may have been one of those abandoned babies whose image broke hearts and opened wallets a decade ago. But nobody came to carry him away to a new life in a foreign country. The charity workers all went elsewhere, or went bust. The world moved on, found other crises to care about. But it is time to remember.

Anyone who gave generously back then will be horrified to know that there are still 160,000 children like Ion in the care of the Romanian state. Conditions are not much better now than they were before millions of pounds poured into the country.

Boys and girls are still routinely abandoned by their families, or wrongly diagnosed as mentally handicapped. Even the healthy ones suffer severe mental trauma inside the institutions where overcrowding, beatings, malnutrition and disease remain common.

“The orphanages are rife with Aids,” says Baroness Nicholson of Winterbourne, who first visited one back in 1990, when the fall of President Ceausescu opened up Romania’s wounds to the world.

“They’re full of other infections. The children are underfed, undernourished, unloved. You get pint-sized adolescents. You get children in cots who seem to be babies – perhaps they weigh eight pounds; in fact they are three years old. Hundreds of children are drugged on a daily basis to keep them quiet, and syringes are used again and again. You get gangs of prostitutes roaming in these orphanages. The children are piled into dormitories as if they were prisoners. All ages and both sexes. The girls get raped and the boys get abused by those older than themselves.”

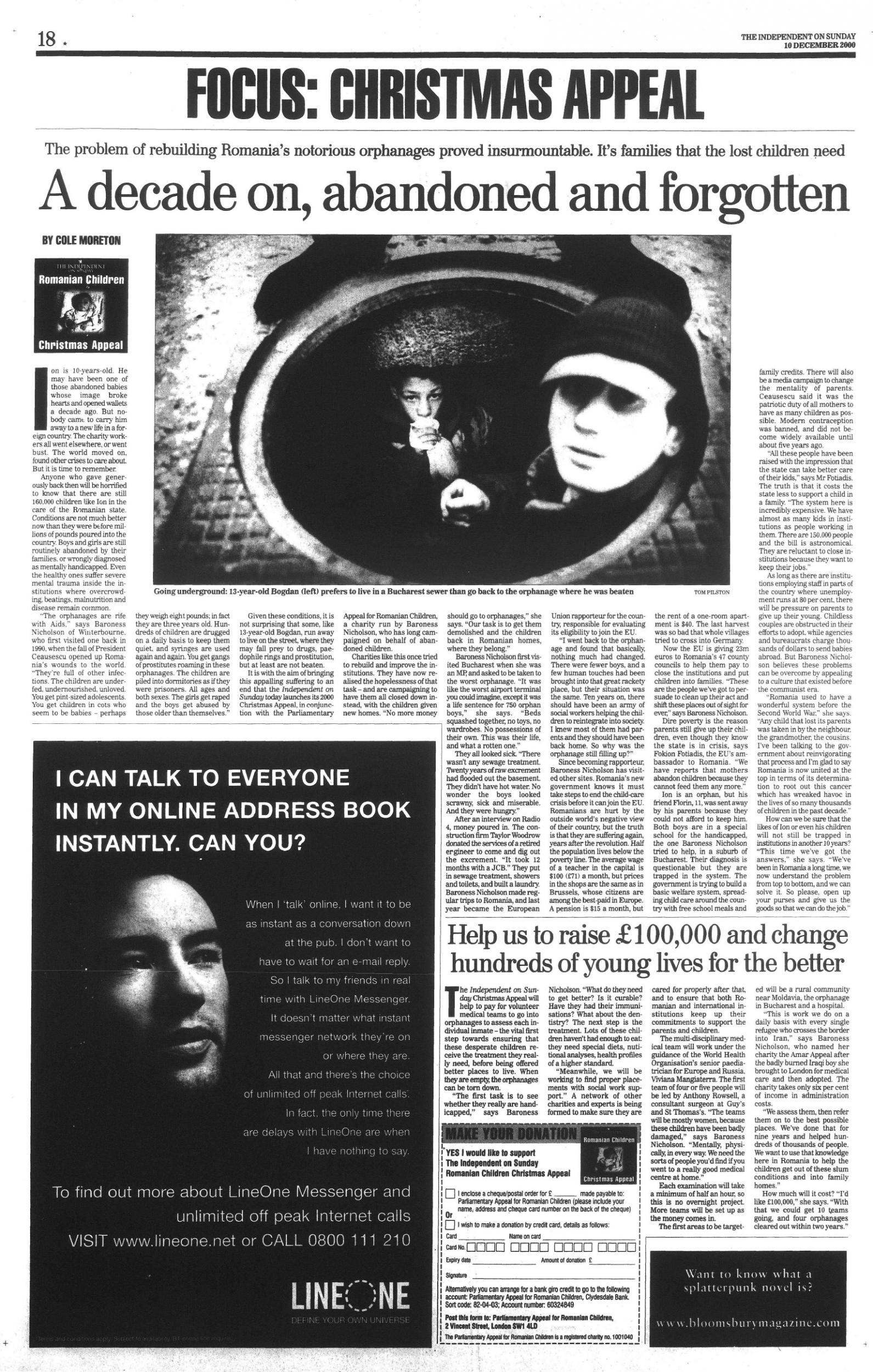

Given these conditions, it is not surprising that some, like 13-year-old Bogdan, run away to live on the street, where they may fall prey to drugs, paedophile rings and prostitution, but at least are not beaten.

It is with the aim of bringing this appalling suffering to an end that The Independent on Sunday today launches its 2000 Christmas Appeal, in conjunction with the Parliamentary Appeal for Romanian Children, a charity run by Baroness Nicholson, who has long campaigned on behalf of abandoned children.

Charities like this once tried to rebuild and improve the institutions. They have now realised the hopelessness of that task – and are campaigning to have them all closed down instead, with the children given new homes. “No more money should go to orphanages,” she says. “Our task is to get them demolished and the children back in Romanian homes, where they belong.”

Baroness Nicholson first visited Bucharest when she was an MP, and asked to be taken to the worst orphanage. “It was like the worst airport terminal you could imagine, except it was a life sentence for 750 orphan boys,” she says. “Beds squashed together, no toys, no wardrobes. No possessions of their own. This was their life, and what a rotten one.”

They all looked sick. “There wasn’t any sewage treatment. Twenty years of raw excrement had flooded out the basement. They didn’t have hot water. No wonder the boys looked scrawny, sick and miserable. And they were hungry.”

The orphanages are rife with Aids. They’re full of other infections. The children are underfed, undernourished, unloved. You get pint-sized adolescents. You get children in cots who seem to be babies – perhaps they weigh eight pounds; in fact they are three years old

After an interview on Radio 4, money poured in. The construction firm Taylor Woodrow donated the services of a retired engineer to come and dig out the excrement. “It took 12 months with a JCB.” They put in sewage treatment, showers and toilets, and built a laundry. Baroness Nicholson made regular trips to Romania, and last year became the European Union rapporteur for the country, responsible for evaluating its eligibility to join the EU.

“I went back to the orphanage and found that basically, nothing much had changed. There were fewer boys, and a few human touches had been brought into that great rackety place, but their situation was the same. Ten years on, there should have been an army of social workers helping the children to reintegrate into society. I knew most of them had parents and they should have been back home. So why was the orphanage still filling up?”

Since becoming rapporteur, Baroness Nicholson has visited other sites. Romania’s new government knows it must take steps to end the child-care crisis before it can join the EU. Romanians are hurt by the outside world’s negative view of their country, but the truth is that they are suffering again, years after the revolution. Half the population lives below the poverty line. The average wage of a teacher in the capital is $100 (£71) a month, but prices in the shops are the same as in Brussels, whose citizens are among the best-paid in Europe. A pension is $15 a month, but the rent of a one-room apartment is $40. The last harvest was so bad that whole villages tried to cross into Germany.

Now the EU is giving €23m (£13.9m) to Romania’s 47 county councils to help them pay to close the institutions and put children into families. “These are the people we’ve got to persuade to clean up their act and shift these places out of sight for ever,” says Baroness Nicholson.

Dire poverty is the reason parents still give up their children, even though they know the state is in crisis, says Fokion Fotiadis, the EU’s ambassador to Romania. “We have reports that mothers abandon children because they cannot feed them any more.”

Ion is an orphan, but his friend Florin, 11, was sent away by his parents because they could not afford to keep him. Both boys are in a special school for the handicapped, the one Baroness Nicholson tried to help, in a suburb of Bucharest. Their diagnosis is questionable but they are trapped in the system. The government is trying to build a basic welfare system, spreading child care around the country with free school meals and family credits.

160,000

children still in the care of the Romanian state

There will also be a media campaign to change the mentality of parents. Ceausescu said it was the patriotic duty of all mothers to have as many children as possible. Modern contraception was banned, and did not become widely available until about five years ago.

“All these people have been raised with the impression that the state can take better care of their kids,” says Mr Fotiadis. The truth is that it costs the state less to support a child in a family. “The system here is incredibly expensive. We have almost as many kids in institutions as people working in them. There are 150,000 people and the bill is astronomical. They are reluctant to close institutions because they want to keep their jobs.”

As long as there are institutions employing staff in parts of the country where unemployment runs at 80 per cent, there will be pressure on parents to give up their young. Childless couples are obstructed in their efforts to adopt, while agencies and bureaucrats charge thousands of dollars to send babies abroad. But Baroness Nicholson believes these problems can be overcome by appealing to a culture that existed before the communist era.

“Romania used to have a wonderful system before the Second World War,” she says. “Any child that lost its parents was taken in by the neighbour, the grandmother, the cousins. I’ve been talking to the government about reinvigorating that process and I’m glad to say Romania is now united at the top in terms of its determination to root out this cancer which has wreaked havoc in the lives of so many thousands of children in the past decade.”

How can we be sure that the likes of Ion or even his children will not still be trapped in institutions in another 10 years? “This time we’ve got the answers,” she says. “We’ve been in Romania a long time, we now understand the problem from top to bottom, and we can solve it. So please, open up your purses and give us the goods so that we can do the job.”

This article first appeared on The Independent’s Focus Page on 10 December 2000

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments