Secret suffering of Ceausescu’s babies: The plight of HIV-positive orphans in Romania

Doctors say it took the revolution to expose the coverup, but even then Romanian state authorities seemed reluctant to act. In 1990, Oliver Gillie visited a Bucharest hospital and was horrified by what he saw

In December 1989, immediately after the fall of communism, the images of starving, naked and sick children found in overcrowded Romanian orphanages shocked the world. In the same month, Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife Elena were executed by firing squad, just moments after a brief trial that found them guilty of genocide, subversion of state power, destruction of public property and theft.

Independent journalist Oliver Gillie travelled to Bucharest in January 1990 and was horrified by what he saw: hundreds of children chained to their cots, unlikely to survive the year, in what was the largest outbreak of non-inherited Aids among children anywhere in the world. The cause was thought to have been dirty needles used in immunisation, or blood transfusions.

For the next 10 years the story was never far from the minds of our readers and in 2000 several flew to Romania and began the process of adopting youngsters. Our Christmas charity appeal that year helped raise £20,000 for the orphans.

A decade on, in 2010, Cahal Milmo went back to Romania and caught up with survivors, many of whom were still waiting for an official apology from the authorities for the starvation, beatings, sexual abuse and lack of care suffered by the estimated 500,000 children who had ended up in the country’s care institutions. For many the psychological scars will never heal.

Romanian Gina Vasile, in her thirties and a data analyst at The Independent, is too young to remember the events clearly, and her parents don’t speak of it. The episode, she says, “casts a dark and shameful shadow over my country’s history. I think people were upset because while we were celebrating the revolution and the liberation from communism, the world chose to focus on the children in the orphanages. This was all hidden from us. We had no idea this terrible thing was happening.”

Thirty years on, while the scandal’s impact is still felt by many, the number of children in care is diminishing and the worst of the orphanages have closed.

In the first part of a new series recalling some of the biggest stories in The Independent’s history, we revisit our reports on a legacy of neglect in Romania.

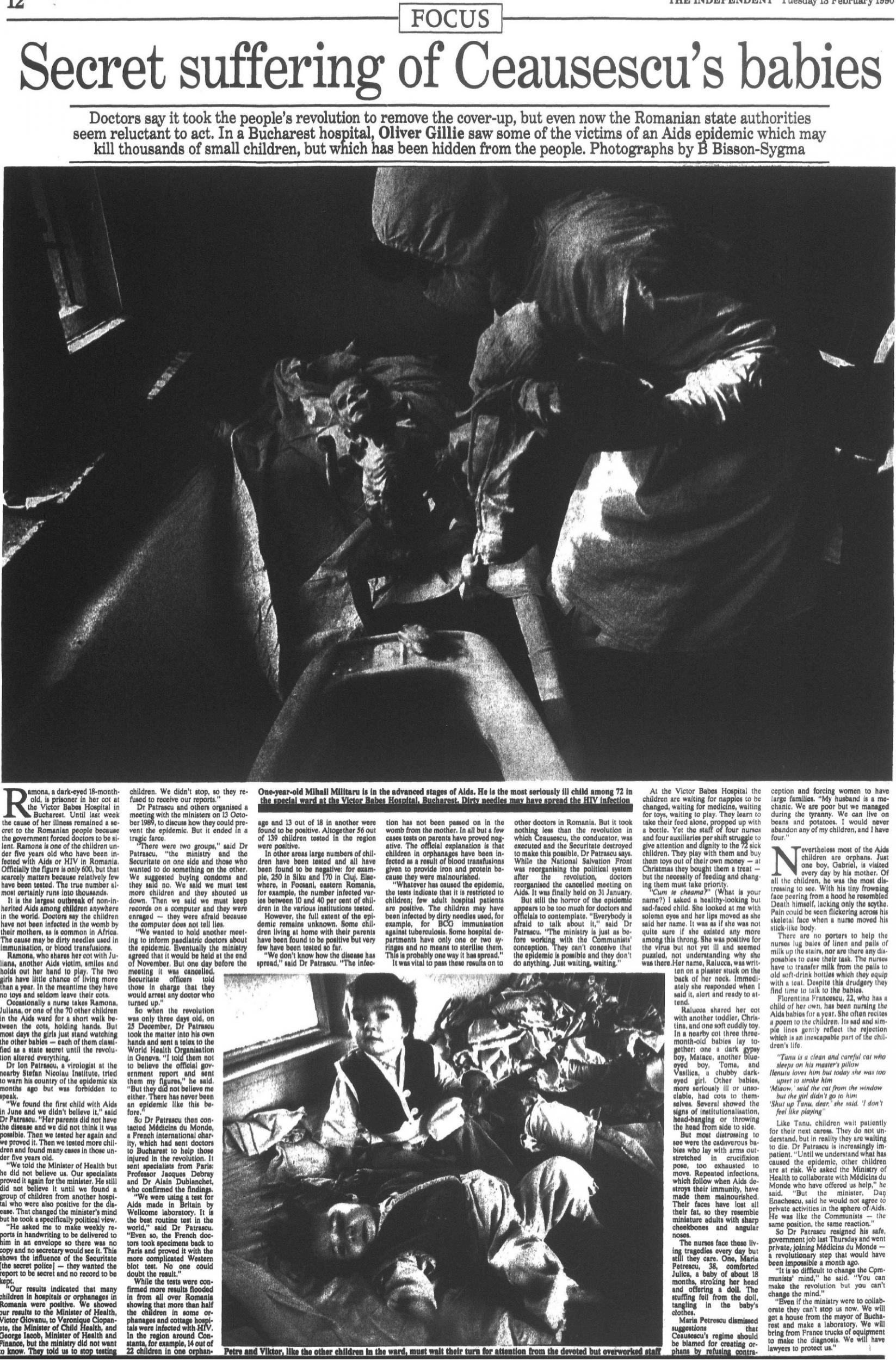

Ramona, a dark-eyed 18-month-old, is prisoner in her cot at the Victor Babes Hospital in Bucharest. Until last week the cause of her illness remained a secret to the Romanian people because the government forced doctors to be silent. Ramona is one of the children under five years old who have been infected with Aids or HIV in Romania. Officially the figure is only 600, but that scarcely matters because relatively few have been tested. The true number almost certainly runs into thousands.

It is the largest outbreak of non-inherited Aids among children anywhere in the world. Doctors say the children have not been infected in the womb by their mothers, as is common in Africa. The cause may be dirty needles used in immunisation, or blood transfusions.

Ramona, who shares her cot with Juliana, another Aids victim, smiles and holds out her hand to play. The two girls have little chance of living more than a year. In the meantime they have no toys and seldom leave their cots.

Occasionally a nurse takes Ramona, Juliana, or one of the 70 other children in the Aids ward for a short walk between the cots, holding hands. But most days the girls just stand watching the other babies – each of them classified as a state secret until the revolution altered everything.

Dr Ion Patrascu, a virologist at the nearby Stefan Nicolau Institute, tried to warn his country of the epidemic six months ago but was forbidden to speak.

“We found the first child with Aids in June and we didn’t believe it,” said Dr Patrascu. “Her parents did not have the disease and we did not think it was possible. Then we tested her again and we proved it. Then we tested more children and found many cases in those under five years old.

“We told the Minister of Health but he did not believe us. Our specialists proved it again for the minister. He still did not believe it until we found a group of children from another hospital who were also positive for the disease. That changed the minister’s mind but he took a specifically political view.

Born in Romania, born again Britain: read about the couples who did more then sympathise

“He asked me to make weekly reports in handwriting to be delivered to him in an envelope so there was no copy and no secretary would see it. This shows the influence of the Securitate, the secret police – they wanted the report to be secret and no record to be kept.

“Our results indicated that many children in hospitals or orphanages in Romania were positive. We showed our results to the Minister of Health, Victor Giovanu, to Veronique Ciopanete, the Minister of Child Health, and George Iacob, Minister of Health and Finance, but the ministry did not want to know. They told us to stop testing children. We didn’t stop, so they refused to receive our reports.”

Dr Patrascu and others organised a meeting with the ministers on 13 October 1989, to discuss how they could prevent the epidemic. But it ended in a tragic farce.

“There were two groups,” said Dr Patrascu, “the ministry and the Securitate on one side and those who wanted to do something on the other. We suggested buying condoms and they said no. We said we must test more children and they shouted us down. Then we said we must keep records on a computer and they were enraged – they were afraid because the computer does not tell lies.

“We wanted to hold another meeting to inform paediatric doctors about the epidemic. Eventually the ministry agreed that it would be held at the end of November. But one day before the meeting it was cancelled. Securitate officers told those in charge that they would arrest any doctor who turned up.”

So when the revolution was only three days old, on 25 December, Dr Patrascu took the matter into his own hands and sent a telex to the World Health Organisation in Geneva. “I told them not to believe the official government report and sent them my figures,” he said. “But they did not believe me either. There has never been an epidemic like this before.”

So Dr Patrascu then contacted Medicins du Monde, a French international charity, which had sent doctors to Bucharest to help those injured in the revolution. It sent specialists from Paris: Professor Jacques Debray and Dr Alain Dublanchet, who confirmed the findings.

“We were using a test for Aids made in Britain by Wellcome laboratory. It is the best routine test in the world,” said Dr Patrascu. “Even so, the French doctors took specimens back to Paris and proved it with the more complicated Western blot test. No one could doubt the result.”

While the tests were confirmed more results flooded in from all over Romania showing that more than half the children in some orphanages and cottage hospitals were infected with HIV. In the region around Constanta, for example, 14 out of 22 children in one orphanage and 13 out of 18 in another were found to be positive. Altogether 56 out of 139 children tested in the region were positive.

In other areas large numbers of children have been tested and all have been found to be negative: for example, 250 in Siku and 170 in Cluj. Elsewhere, in Focsani, eastern Romania, for example, the number infected varies between 10 and 40 per cent of children in the various institutions tested.

However, the full extent of the epidemic remains unknown. Some children living at home with their parents have been found to be positive but very few have been tested so far.

“We don’t know how the disease has spread,” said Dr Patrascu. “The infection has not been passed on in the womb from the mother. In all but a few cases tests on parents have proved negative. The official explanation is that children in orphanages have been infected as a result of blood transfusions given to provide iron and protein because they were malnourished.

“Whatever has caused the epidemic, the tests indicate that it is restricted to children; few adult hospital patients are positive. The children may have been infected by dirty needles used, for example, for BCG immunisation against tuberculosis. Some hospital departments have only one or two syringes and no means to sterilise them. This is probably one way it has spread.”

Everybody is afraid to talk about it. The ministry is just as before working with the Communists’ conception. They can’t conceive that the epidemic is possible and they don’t do anything. Just waiting, waiting

It was vital to pass these results on to other doctors in Romania. But it took nothing less than the revolution in which Ceausescu, the conducator, was executed and the Securitate destroyed to make this possible, Dr Patrascu says. While the National Salvation Front was reorganising the political system after the revolution, doctors reorganised the cancelled meeting on Aids. It was finally held on 31 January.

But still the horror of the epidemic appears to be too much for doctors and officials to contemplate. “Everybody is afraid to talk about it,” said Dr Patrascu. “The ministry is just as before working with the Communists’ conception. They can’t conceive that the epidemic is possible and they don’t do anything. Just waiting, waiting.”

At the Victor Babes Hospital the children are waiting for nappies to be changed, waiting for medicine, waiting for toys, waiting to play. They learn to take their feed alone, propped up with a bottle. Yet the staff of four nurses and four auxiliaries per shift struggle to give attention and dignity to the 72 sick children. They play with them and buy them toys out of their own money – at Christmas they bought them a treat – but the necessity of feeding and changing them must take priority.

“Cum te cheama?” (What is your name?) I asked a healthy-looking but sad-faced child. She looked at me with solemn eyes and her lips moved as she said her name. It was as if she was not quite sure if she existed any more among this throng. She was positive for the virus but not yet ill and seemed puzzled, not understanding why she was there.Her name, Ralucca, was written on a plaster stuck on the back of her neck. Immediately she responded when I said it, alert and ready to attend.

Ralucca shared her cot with another toddler, Christina, and one soft cuddly toy. In a nearby cot three three-month-old babies lay together: one a dark gypsy boy, Matace, another blue-eyed boy, Toma, and Vasilica, a chubby dark-eyed girl. Other babies, more seriously ill or unsociable, had cots to themselves. Several showed the signs of institutionalisation, head-banging or throwing the head from side to side.

But most distressing to see were the cadaverous babies who lay with arms outstretched in crucifixion pose, too exhausted to move. Repeated infections, which follow when Aids destroys their immunity, have made them malnourished. Their faces have lost all their fat, so they resemble miniature adults with sharp cheekbones and angular noses.

The nurses face these living tragedies every day but still they care. One, Maria Petrescu, 38, comforted Julica, a baby of about 18 months, stroking her head and offering a doll. The stuffing fell from the doll, tangling in the baby’s clothes.

Maria Petrescu dismissed suggestions that Ceausescu’s regime should be blamed for creating orphans by refusing contraception and forcing women to have large families. “My husband is a mechanic. We are poor but we managed during the tyranny. We can live on beans and potatoes. I would never abandon any of my children, and I have four.”

Nevertheless most of the Aids children are orphans. Just one boy, Gabriel, is visited every day by his mother. Of all the children, he was the most distressing to see. With his tiny frowning face peering from a hood he resembled Death himself, lacking only the scythe. Pain could be seen flickering across his skeletal face when a nurse moved his stick-like body.

There are no porters to help the nurses lug bales of linen and pails of milk up the stairs, nor are there any disposables to ease their task. The nurses have to transfer milk from the pails to old soft-drink bottles which they equip with a teat. Despite this drudgery they find time to talk to the babies.

Florentina Francescu, 22, who has a child of her own, has been nursing the Aids babies for a year. She often recites a poem to the children. Its sad and simple lines gently reflect the rejection which is an inescapable part of the children’s life.

“Tanu is a clean and careful cat who

sleeps on his master’s pillow

Ilenuta loves him but today she was too

upset to stroke him

‘Miaow,’ said the cat from the window

but the girl didn’t go to him

‘Shut up Tanu, dear,’ she said. ‘I don’t

feel like playing’”

Like Tanu, children wait patiently for their next caress. They do not understand, but in reality they are waiting to die. Dr Patrascu is increasingly impatient. “Until we understand what has caused the epidemic, other children are at risk. We asked the Ministry of Health to collaborate with Medicins du Monde who have offered us help,” he said. “But the minister, Dan Enachescu, said he would not agree to private activities in the sphere of Aids. He was like the Communists – the same position, the same reaction.”

So Dr Patrascu resigned his safe, government job last Thursday and went private, joining Medicins du Monde – a revolutionary step that would have been impossible a month ago.

“It is so difficult to change the Communists’ mind,” he said. “You can make the revolution but you can’t change the mind.”

“Even if the ministry were to collaborate they can’t stop us now. We will get a house from the mayor of Bucharest and make a laboratory. We will bring from France trucks of equipment to make the diagnosis. We will have lawyers to protect us.”

This article first appeared on The Independent's Focus page on 13 February 1990

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments