Women were at the heart of Libya’s revolution. Ten years on, they risk death calling for their rights

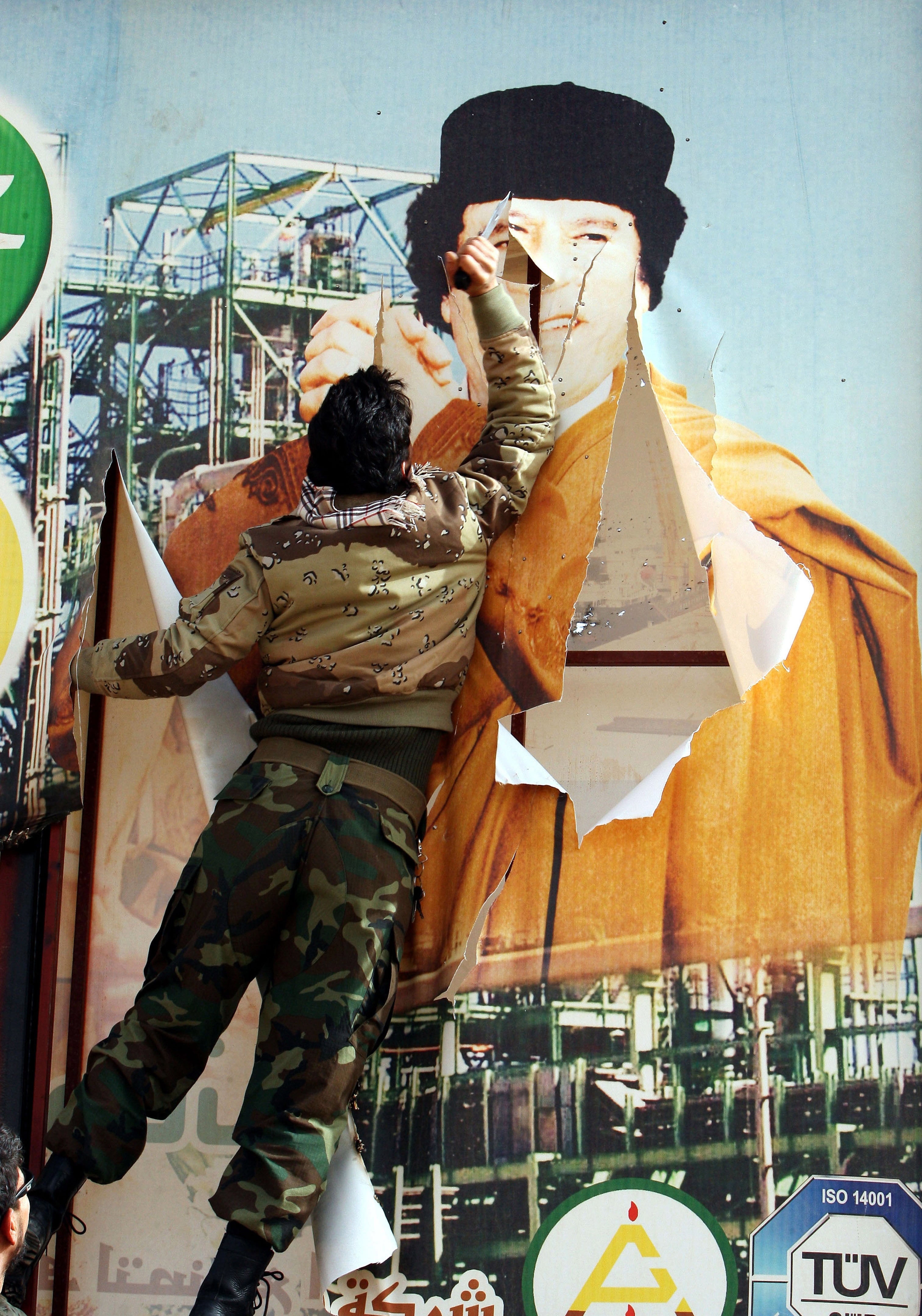

From playing a prominent role in the revolution against Gaddafi, Libyan women have been increasingly sidelined in attempts to get the country back to any form of stability, reports Bel Trew

It wasn’t until she saw her cousins, rights activists Salwa and Iman, leading a daring protest outside a courthouse in Benghazi that Hala Bugaighis realised something truly huge was happening.

It was February 2011. Hosni Mubarak had stepped down in neighbouring Egypt just the week before and that revolutionary fervour had spilled over the borders into Libya’s second city.

Hala Bugaighis, then a 31-year-old commercial lawyer, was more than 1,000km west in Tripoli, a stronghold of Muammar Gaddafi who had ruled the country with an iron fist for more than 40 years.

When the rallies in east Libya first broke out, she was certain the regime would quickly, brutally and nonchalantly crush them.

And so, she was surprised to see signs of it panicking.

She watched the authorities bus in Gaddafi supporters to Tripoli’s central square for rallies praising the leader. Armed forces were deployed to patrol the streets and closely monitor everything. It wasn’t even safe to visit the supermarket.

On the other side of the country, her female cousins Salwa (a prominent human-rights lawyer) and Iman (an orthodontist) were leading the fledgling revolt.

“I was really worried the regime would oppress the uprising and it would all be in vain, people would die,” says Hala explaining how her family were particularly concerned about violence: the Benghazi wing of the family were well-known opposition figures.

“But then I saw my cousins at the protest at the court and I thought this is happening. This is real.

“My strongest memory was thinking these are the right people to be leading it.”

The revolution which erupted in Libya exactly ten years ago quickly tumbled into a bloody civil war. Hala focused on survival as Tripoli was heavily bombed during the NATO intervention.

Even after Gaddafi’s killing in October 2011 and the unravelling of his regime, the hopes of a better country were swamped by tidal waves of conflict that still roll on today.

Over the years the fight has shifted into territorial battles between fiefdoms of heavily armed militias that are manned exclusively by men. The dizzying number of rival administrations that would come and go were also dominated by men.

Women, who had always led civil society and were at heart of the uprising, would find their voices drowned by gunfire.

As the country became increasingly violent and conservative, women learned that they risked their lives if they spoke out.

Hala’s cousin Salwa Bughaighis became a leading figure in the National Transitional Council which ran eastern Libya, but stepped down from the role when it became clear the male politicians were fighting each other for power and Islamists were gaining a stranglehold. She maintained her political activism amid the rise of armed jihadists.

And for this, she would be silenced. In 2014 she was assassinated by armed groups in broad daylight at her home.

Two other prominent women’s-rights activists, Fariha Barkawi and Salwa Yunis al-Hinaid, were also murdered in east Libya in quick succession that same year.

Women in Libya continue to be threatened, assaulted, raped, kidnapped, disappeared and murdered for speaking out.

In November, in the middle of the latest round of peace talks, Hanan Al-Barassi, a vocal critic of corruption and armed groups, was gunned down in broad daylight in Benghazi’s busy city centre.

“From 2014 it hasn’t stopped. There has been a string of assassinations of women. It made women fear being in public spaces talking about human and women’s rights,” says Hala, who despite the dangers decided to set up her own women’s rights charity called Jusoor after Salwa’s murder.

“There was huge repression. The clear message was: human and women’s rights were not welcome.”

Like many women’s-rights defenders, Hala has received death threats and physical violence, even though, as she says, women are the only group in Libya who have no blood on their hands.

Another women’s-rights defender, Rida al-Tubuly, a pharmacology professor and international law consultant, feared she would be killed after she addressed the UN Security Council in 2019 about this very issue: violence against women.

“Other women and I have been accused of being foreign spies and trying to destroy the fabric of the society,” she tells The Independent.

“Women were trying to bring human rights issues to the table – while men were largely fighting for their interests and power. “

The first step back

For Rida, the penny dropped almost immediately after the revolution. In 2011, she set up ‘Together we build it’, an NGO working on the inclusion of women in the political and peace process. She was dreaming of a new country where “women issues were Libya’s issues and Libya’s issues are women’s issues”.

But her fears that the uprising had been “hijacked” was confirmed just a few days after Gaddafi’s death during the inaugural speech by Libya’s then-interim leader Mustafa Mohammed Abdul Jalil.

He was supposed to announce the success of the Libyan revolt and the birth of a new nation. Everyone who was not physically present was glued to their television sets.

“All Libyans were waiting for him to talk about how they will lay down the basis of a democratic civilised advanced country,” she says.

“But the main priority for him was announcing that men can marry four women.

“It was a shock for everyone. Even the men were laughing about it, saying that if the priority was men marrying four wives, that could have been achieved without a war.”

Mr Abdel-Jalil had decided to use that foundational speech to declare, among other things, that a Gaddafi-era law that placed restrictions on multiple marriages (a tenet of Islamic Sharia law) would be scrapped.

It was a frightening blow for women at such a tentative moment: the country still had to be built from scratch, including institutions, the constitution, laws and with that, the place of women in the new society.

It is unclear whether Mr Abdel-Jalil was proving his piousness or whether he was trying to placate the newly influential Islamists that would go on to hold significant power in Libya.

Rida felt like it was the start of the erosion of rights for Libya’s women, who are among the most educated and literate in the Middle East region. It marked the beginning of the “fight to preserve what we already had”.

Like Rida, Hala says it was also worrying as it came very quickly after the violent murder of Gaddafi, who was lynched near a storm drain: an action which also deeply concerned many women.

“It was the first time I was scared from the revolution,” Hala says.

The rule of the gun

It is hard to build a peaceful country when the best paid jobs in town are with the militias.

Instead of being demilitarised, the brigades of armed volunteers who had fought in Libya’s 2011 war were absorbed into the various arms of the state in a messy ad hoc system. Their numbers swelled and turf wars erupted.

The lawlessness crescendoed with the 2012 murder of Chris Stevens, the US ambassador, during an attack on the US mission in Benghazi. Nine months after that the then prime minister Ali Zeidan was kidnapped by dozens of gunmen and only freed when local militias stormed the Tripoli police station where he was being held.

Brigades of ex-rebels, with tanks and grad missiles, abducted foreign diplomats and intermittently laid siege to the parliament to force the state to meet their demands.

Despite this, in 2013 the then Libyan authorities spent hundreds of millions of dollars funding the armed groups in a desperate attempt to control them by integrating them into the security forces.

Civilian politics was dictated by guns, and rights defenders were increasingly a target.

Despite the dangers, Salwa was determined women would still have a seat at the table and took a lead in the country’s national dialogue initiative, aimed at curtailing the lawlessness and violence. She wanted more to join the movement: in the spring of 2014, she met her cousin Hala in Amman and encouraged her to transition from commercial law to civil society.

“I said I don’t believe in non-profit, but she was talking so passionately about the civil state that she was dreaming of, it was inspiring. We spoke for four hours straight,” Hala recalls.

Salwa planned to return to Benghazi to vote in the messy June parliamentary election. She met Rida, a friend of hers, the day before she flew and admitted she had concerns she might be killed.

“Salwa told me, ‘I am not sure I will be safe there’, and I asked her why she was taking the risk,” recalls Rida. “She replied, ‘I must go vote.’’

The 2014 elections were chaotic. Less than half the eligible voters turned out. In the troubled city of Derna, which would later go on to become an Islamic State stronghold, no voting took place at all as polling stations were closed for security reasons.

At least four people, most of them members of the security forces, were killed in Benghazi in heavy clashes.

Despite this, Salwa posted a photo of herself casting her ballot. She encouraged others to vote in an interview with a local TV station. A few hours later, an armed car with a black flag appeared outside her home.

Gunmen stormed the house, shot her dead, and disappeared her husband. It was terrifyingly brazen: Salwa had live posted the arrival of her killers on Facebook.

“I knew she had been receiving threats,” says Hala, with a crack in her voice.

“I called her many times and she didn’t answer.”

After Salwa’s killing, with her words of encouragement still lingering, Hala decided to set up Jusoor, “a think and do tank” which has run several projects including a businesswomen incubator in 2018.

But this second wave of civil society, as Hala calls it, was working in impossible circumstances.

Amid the rising lawlessness, most of the international community left the country, “and we felt all alone”.

The light at the end of the tunnel?

Rida tried hard to ignore the TV channels accusing her of being a foreign spy and the mounting death threats from people who said they knew where she lived.

It was already becoming difficult to run a woman’s rights NGO amid the continuous cycles of war which took over Tripoli in 2014, 2017 and most recently in 2019, when renegade eastern commander Khalifa Hafter launched an ill-fated year-long offensive to seize the capital.

Rida moved most of her initiatives and workshops online, because of the fighting and the fact they were being attacked by conservatives angered that women are trying to own their own space.

But even that proved tricky, given the regular internet and power outages across a country that was steadily falling apart.

For her, the death threats and cyberviolence really escalated in November 2019 when she was invited to address the UN Security Council about violence against women and the need for freedom of expression.

“It’s pretty terrifying in a country where there is no rule of law and weapons are everywhere,” she says. “The price of a bullet is just 5 Libyan dinars (80p)”.

Over the last two years, after nearly a decade of conflict and shifting plates of power, the country blossomed into a full-blown proxy war with Turkey intervening militarily to protect an UN-backed government in Tripoli and countries like the UAE, Russia and Egypt supporting Haftar’s factions in the east.

While there has been some recent sign of progress this month, with a new transitional government unifying the warring factions, women were largely frozen out of that decision-making process.

In the United Nations-brokered peace negotiations last year which worked towards the new transitional government, women were woefully underrepresented. Of the 75 Libyans who participated in the Tunis talks, only 17 were women.

Libya’s new interim leaders, chosen during the latest round of peace talks in Geneva in February, are all men, including the new male prime minister, Abdul Hamid Dbeibah.

The cabinet has still yet to be picked and so Hala is drawing up a list of potential female candidates for each role.

Libya’s outgoing UN envoy Stephanie Williams, who worked on greater female participation in the peace process, says that she hopes that women are not “pigeonholed” in ministries like social or family affairs.

“They should be appointed to sovereign ministries,” she tells The Independent. “Dbeibah needs to be held firmly accountable for serious inclusion of women in the government. Why not have a female foreign minister or finance minister, for instance?”

Meanwhile, the threat of violence against women continues.

Hanan Al-Barrassi’s murder in November last year came just 16 months after the disappearance of another prominent Benghazi woman, rights activist and parliamentarian Siham Sergewa. She was kidnapped by armed men in the middle of the night from her home, after openly criticising the war on Tripoli. She is still missing.

Every woman who stands up for herself does so at great risk. But that hasn’t deterred them.

Hala hopes her list of women candidates for the ministerial positions will help Libyans and the international community see the role of women differently. Ironically she says, one of the biggest obstacles women in Libya face is the fact they are not in the brigades and on the battlefields. This has meant “they are not seen as part of the equation”.

Instead the “troublemakers and peace spoilers” are routinely invited to the talks and considered for the positions of power.

And so, she wants to make sure that women are not just token afterthoughts but rightfully given a place front and centre in the halls of power.

Rida acknowledges that while “Libya is hell now”, there is still hope in the new government and the determination of women to keep fighting for change.

“We are seeing a light at the end of the tunnel but we don’t know how long this tunnel is,” she says.

“Despite the risk, Libyan women are sacrificing themselves to help Libyans find a shortcut to that end.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks