The killing of a soldier and his six-year-old son paints a chilling picture of Syria’s war

The longer it continues, the more this brutal conflict rips away humanity, says Robert Fisk

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the great Syrian military residential complex on the road to Lebanon, some very serious men are gathering to talk about the killing of a young army captain and his six-year old son.

There are many soldiers, a cluster of generals and colonels, the dead man’s brother and a man from the Damascus suburb of Qudsayya – where the captain and his little boy were murdered – with an extraordinary message: the killer’s parents have told him he is no longer their son.

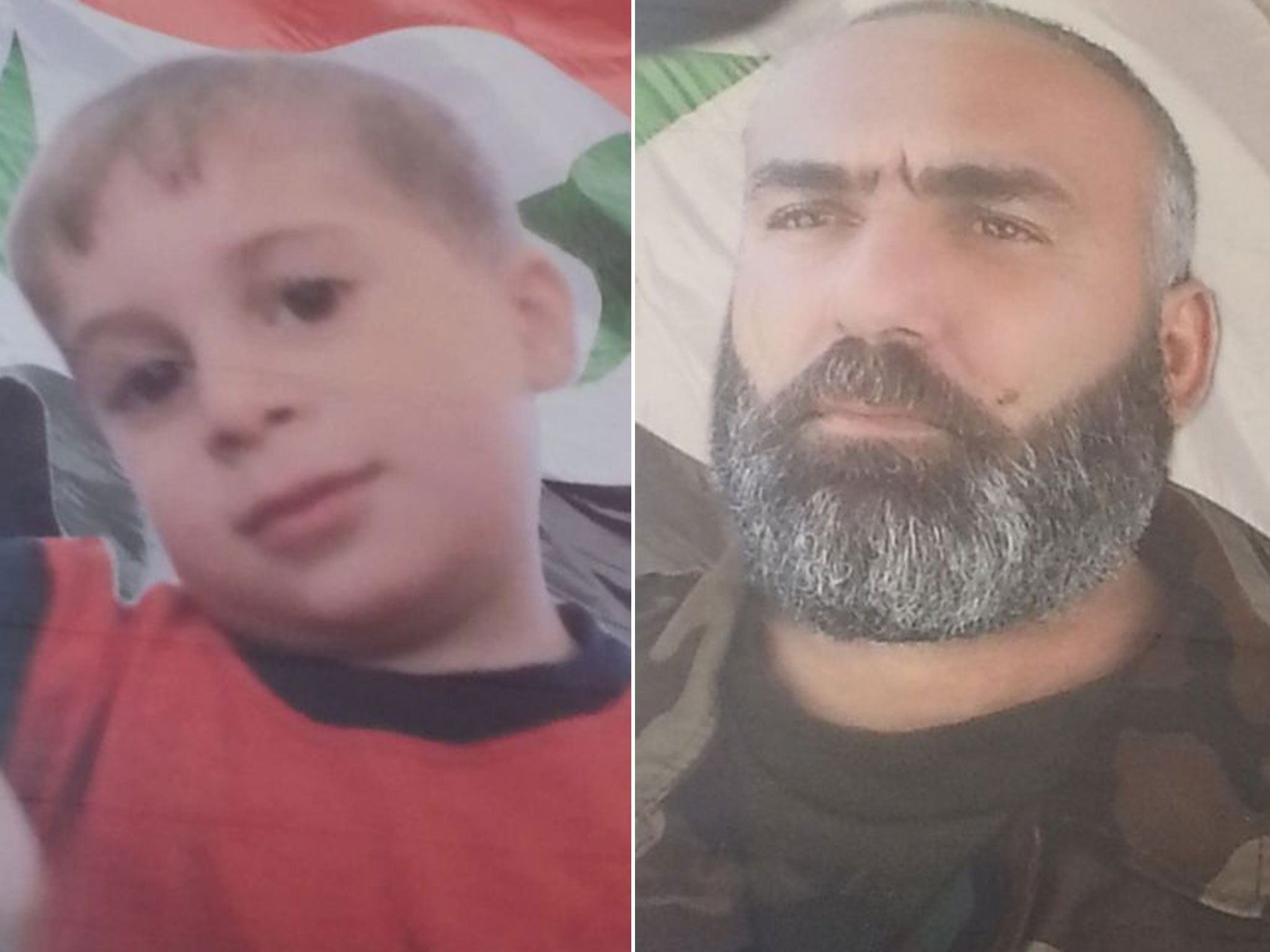

Younis Mustafa, the 39-year old army captain who died as he went shopping with his little boy on 21 February, stares down at us from a martyr’s poster – bearded, solemn, a photograph of six-year-old Ammar to his left, smiling confidently into the camera. Everyone in Damascus knows the story of Younis Mustafa, but when his brother Hassan talks about the killing, it acquires a distressing human edge.

“It was 3.30 in the afternoon when I received a phone call from his wife. She was with him and their other two children when he was surrounded on the street outside a supermarket. She had borrowed another woman’s mobile phone at the place where it happened to call me. All she said was: ‘They have killed your brother and my son.’ I didn’t answer and she closed the line.”

Usaima Ali Ghanem is 34 but she was now at home, her brother-in-law representing her closest family at this “reconciliation” meeting, a negotiation between the dead man’s next of kin and the group of men from Qudsayya who would arrive to offer their condolences on behalf of the neighbourhood in which Captain Mustafa was killed.

February 21st was a Friday, the Muslim Sabbath, and he and his family had felt safe in Qudsayya; although armed men still moved around the district, it contained one of the “reconciliation committees” of well-known local figures who have managed to talk to rebel leaders as well as the army. But as his wife and his other two children, Hala and Hassan, watched from the family car, they saw a group of men surround the army captain. They had a rifle, and fired first at the six-year old – in his back – and, as the father tried to hold his dying child, they shot him too. Then the killers ran away. Several local people rushed to protect Usaima and the two children in the car. One report says the men took the captain’s body away, leaving the child on the pavement. Half an hour later, “reconciliation committee” men brought the body back.

This “reconciliation committee” – and it deserves the quotation marks – had given confidence to the family’s shopping expedition. But alas, one of the mourners told me that the very man who shot Captain Mustafa had been freed from a government prison in a recent amnesty arranged by the committee.

In a hall decorated with Syrian flags and containing plastic chairs and tables set in a rectangle for the condolences, the family sat grimly, waiting for the delegation of men who would sit opposite them. Then a general received a mobile phone call to say that the delegation could not arrive because of a bombardment.

But one man made it through, Nazzir Halimeh, sorrowful but his hair tangled, clearly still fearful from the shelling he had to drive through. “We are so sorry,” he said. “It is our duty to express our condolences to this family. And we have to tell them that the family of the man who killed Captain Mustafa have now disowned their son. They told him that he would never be their son again. All the families of the men involved have told their sons to leave their homes.”

There were names to these men. One was called Ghandour, another al-Rifai and – probably the murderer – a man called al-Halibi. Being a soldier in civilian clothes did not save the captain. The army regard soldiers killed in fighting as casualties of war. But this was different.

By chance, among the military mourners was Colonel Omar Shaaban from the Tel Besih district in Homs, wounded three times in battle, refusing an offered retirement from the army, the marks from one bullet still visible on his face – the round passed through his left cheek through his mouth and out through his right cheek.

His story, however, was darker than his wounds. When insurgents took over his home area in Homs, the family fled but his brother, a schoolteacher, stayed behind. “They tried to use him to get me to defect, but I refused,” Colonel Shaaban said. “They told him they wanted him to join the terrorists and he also refused. So for both reasons – because of me and because of his refusal – they shot him dead.” Some military and civilian friends of Captain Mustafa were listening to Colonel Shaaban in silence. I did a reporter’s duty. What were their religions? And they told me. Sunni, Christian, Alawite, Druze and Ismaeili.

Reconciliation is a rich fruit which must be consumed all over Syria in the years to come. For generations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments