The Isis reality TV show — Victims confront terrorists on controversial Iraqi TV show

'In the Grip of the Law' - in which terrorists recount their attacks before facing down one of their victims - has been condemned by human rights groups

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The confessions of convicted terrorists are being broadcast on an Iraqi reality TV show in which they are also forced to face the relatives of victims.

"In the Grip of the Law", which is produced by the state-run Al Iraqiya channel in cooperation with the Iraqi Ministry of Interior, has been launched as part of a media effort to attack the Islamic extremist group Isis and garner public support for the Iraqi forces that were humiliated by Isis this summer.

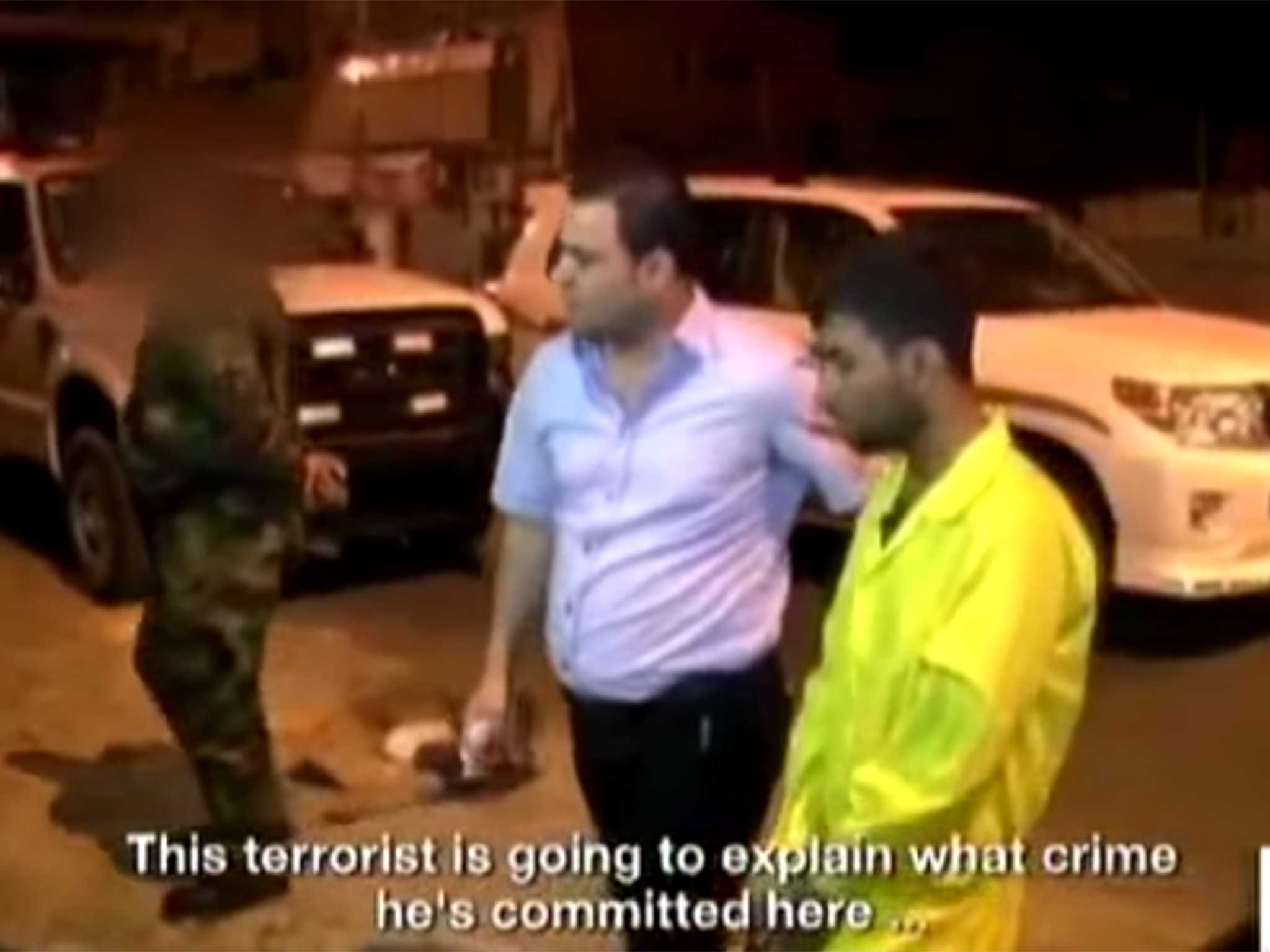

Every Friday the show's host, Ahmed Hassan, who has reportedly become a target himself, quizzes convicted terrorists in shackles and bright yellow prison jumpsuits.

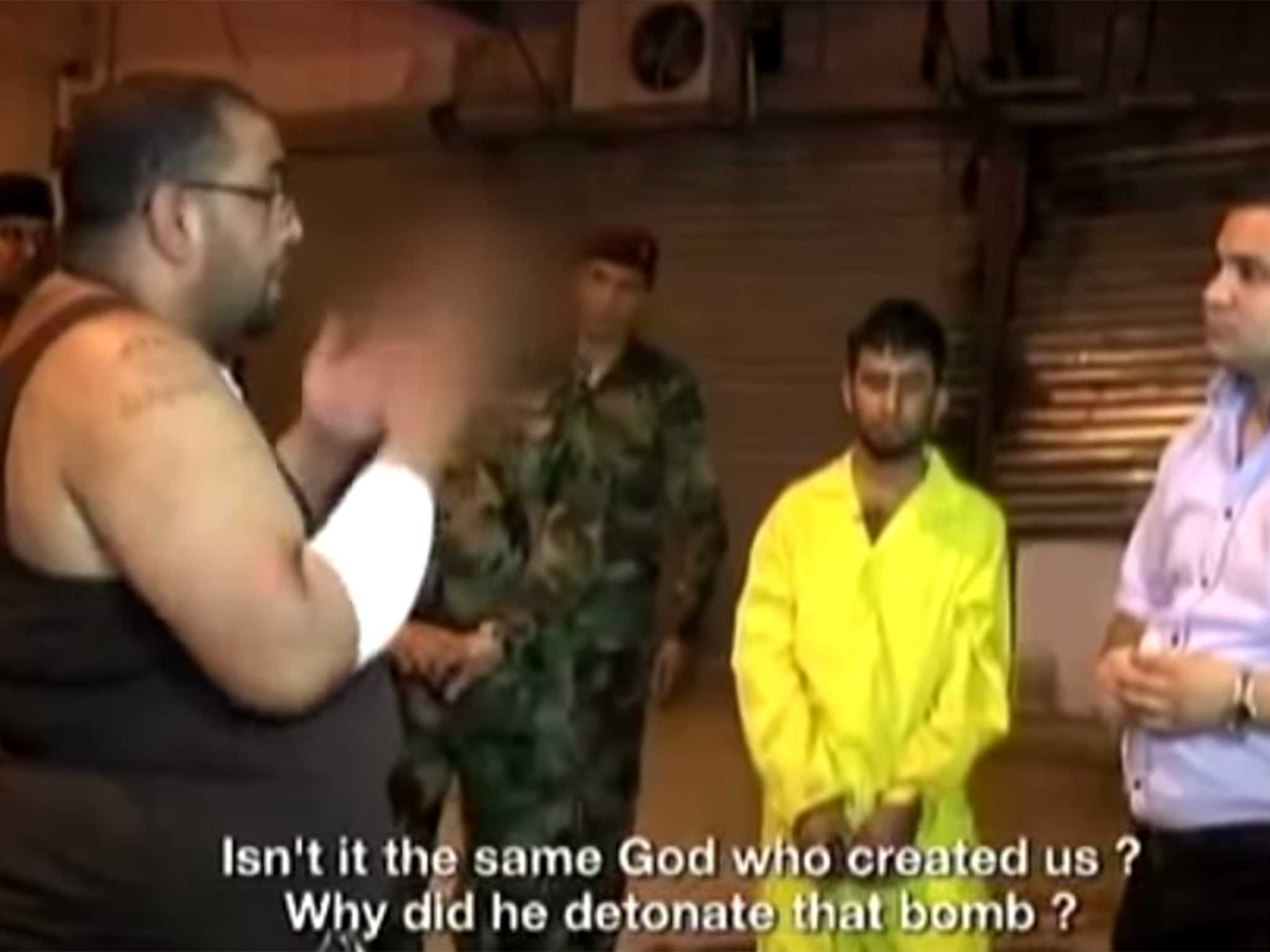

The relatives of victims of terrorist attacks are then brought before the prisoners, often either in a rage or on the verge of tears.

One of the men to feature on the programme is 21-year old Haider Ali Motar, convicted one month ago for helping to carry out a string of Baghdad car bombings on behalf of Isis.

The crew began filming at the scene of one of the attacks for which Motar was convicted, with a sizeable military escort in tow. Soldiers shooed away interested bystanders and drivers frustrated by the consequent traffic.

After being pulled from an armoured vehicle, a shackled Motar found himself face-to-face with the seething relatives of the victims of the attack. "Give him to me — I'll tear him to pieces," one of the relatives roared from behind a barbed wire barrier.

A cameraman pinned a microphone on Motar's bright yellow prison jumpsuit as he stood alongside a busy Baghdad highway looking bewildered by his surroundings.

"Say something," the cameraman said to him.

"What am I supposed to say?" a visibly panicked Motar asked.

"It's a mic check! Just count: 1,2,3,4..."

Host Hassan quizzed Motar, before bringing out one of the victims, a young man in a wheelchair who lost his father in one of the attacks; the convict began weeping, as the cameras rolled.

Iraq has seen near-daily car bombs and other attacks for more than a decade, both before and after the withdrawal of U.S.-led troops at the end of 2011. But the central message of the show, the filming of which began last year, is that the security forces will bring perpetrators to justice.

The episodes often detail the trail of evidence that led security forces to make the arrest. Police allow the camera crew to film the evidence — explosive belts, bomb-making equipment or fingerprints and other DNA samples.

Hassan told The AP: "We wanted to produce a program that offers clear and conclusive evidence, with the complete story, presented and shown to Iraqi audiences.

"Through surveillance videos, we show how the accused parked the car, how he blew it up, how he carries out an assassination.

"We show our audiences the pictures, along with hard evidence, to leave no doubts that this person is a criminal and paying for his crimes."

All of the alleged terrorists are shown confessing to their crimes in one-on-one interviews. Hassan said the episodes are only filmed after the men have confessed to a judge, insisting it is "impossible" that any of them are innocent.

"The court first takes a preliminary testimony and then they require a legal confession in front of a judge," Hassan explained. "After obtaining the security and legal permission, we are then allowed to film those terrorists."

Human rights groups have long expressed concern over the airing of confessions by prisoners, many of whom have been held incommunicado in secret facilities.

"The justice system is so flawed and the rights of detainees, especially those accused of terrorism (but not only) are so routinely violated that it is virtually impossible to be confident that they would be able to speak freely," Donatella Rovera, of Amnesty International, told AP in an email.

"In recent months, which I have spent in Iraq, virtually every family I have met who has a relative detained has complained that they do not have access to them, and the same is true for lawyers."

, Amnesty cited longstanding concerns about the Iraqi justice system, "where many accused of terrorism have been convicted and sentenced to long prison terms and even to death on the basis of 'confessions' extracted under torture."Such concerns are rarely if ever aired on Iraqi TV, where wall-to-wall programming exalts the security forces. Singers embedded with the troops sing nationalist songs during commercial breaks. In another popular program, called "The Quick Response," a traveling correspondent interviews soldiers, aiming to put a human face on the struggle against the extremists.

Iraqi forces backed by Shiite and Kurdish militias, as well as U.S.-led coalition airstrikes, have clawed back some territory following the army's route last summer, when commanders disappeared, calls for reinforcements went unanswered and many soldiers stripped off their uniforms and fled. But around a third of the country — including its second largest city, Mosul — remains under the firm control of militants, and nearly every day brings new bombings in and around the capital.

Back at the makeshift barricade set up for "In the Grip of the Law," security officials insist they are nevertheless sending a message of deterrence.

"Many of these terrorists feel a lot of remorse when they see the victims," said the senior intelligence officer overseeing the shoot, who declined to be named since he often works undercover. "When people see that, it makes them think twice about crossing the law."

Additional reporting by Associated Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments