Syria war: Doctor reveals horrific torture in prison as Amnesty International estimates 17,723 detainees killed

‘Guards would come to the bars and say: ‘Knock on the door when they die.’ It was a famous saying’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A Syrian doctor has told how he was tortured and forced to watch other prisoners die in regime jails as a report reveals almost 18,000 detainees have died during the country’s brutal civil war.

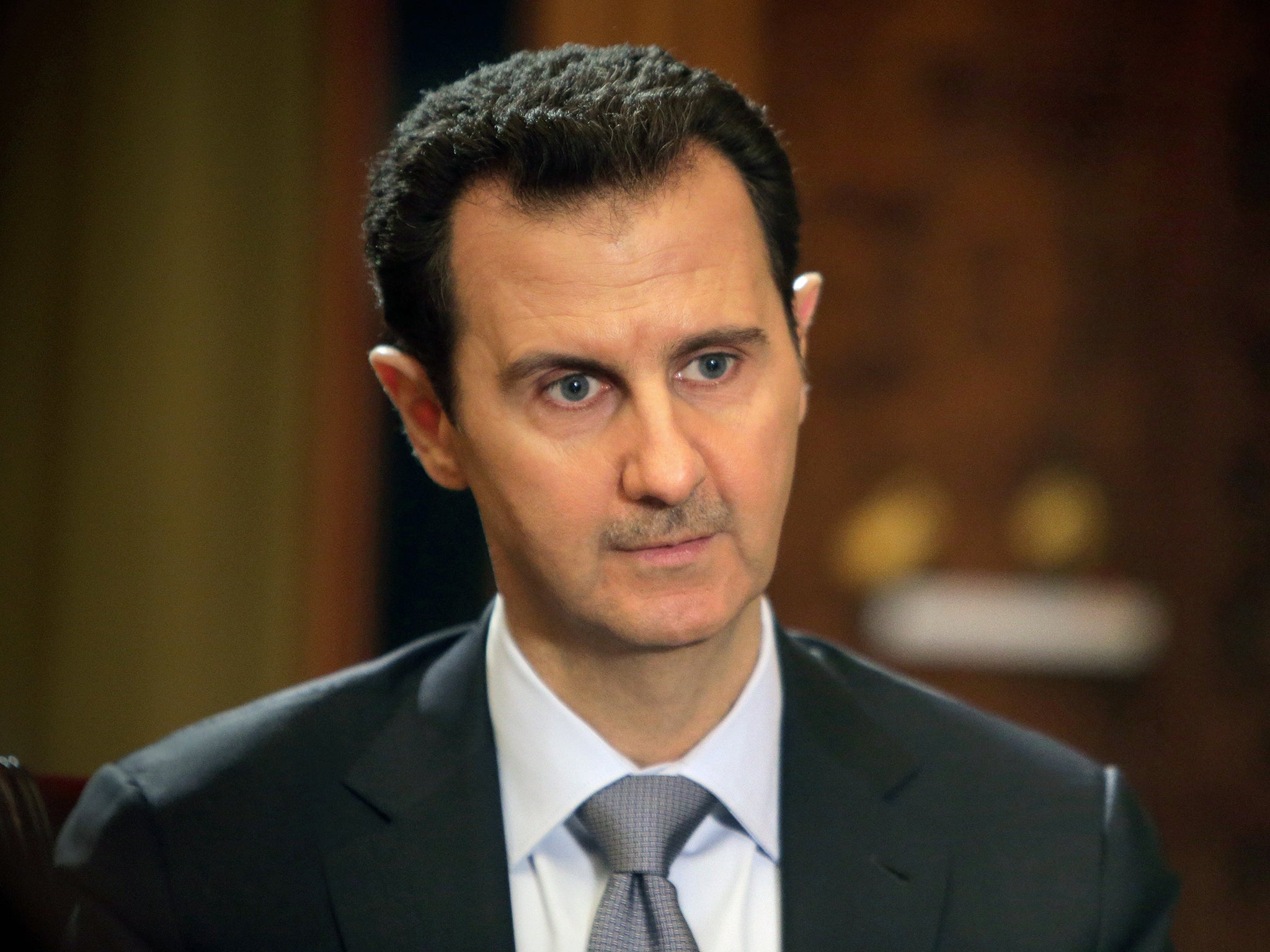

Amnesty International says an average of 10 people have been killed every day by beatings, disease and neglect in secretive detention facilities controlled by Bashar al-Assad’s forces over the past five years.

Survivors have given horrific accounts of rape and abuse in overcrowded cells where prisoners are left to suffocate and succumb to illness or starvation.

Bashar Farahat, a 32-year-old doctor, was working in a hospital in Latakia province when he was arrested by officers from Syria’s notorious Military Intelligence Directorate in July 2012.

“The minute you get in the car you disappear,” he told The Independent. “You don’t know anything about the world outside and the world outside doesn’t know anything about you.

“Once you are detained you become the property of the guards and the interrogators can do anything to you to get a confession.”

Mr Farahat believes he was reported to the authorities for supporting anti-government protests and treating those injured in the ensuing regime crackdown.

The trainee paediatrician was taken to the headquarters of the Military Intelligence branch in Latakia and subjected to a so-called “welcome party”, where new arrivals are beaten publicly by groups of officers armed with metal bars and electric cables.

“They hit you with whatever they want, whatever they have – I arrived alone, so I had a full party,” he said, with a bitter laugh.

It was only the start of the ordeal Mr Farahat would go through for a fortnight of torture at the hands of government interrogators, who were searching for the names of other suspected revolutionaries to hunt down.

Unsatisfied, officials transferred him to the much larger headquarters of Military Intelligence Branch 291 in Damascus.

“I was blindfolded and they handed me over to an officer who started insulting me,” Mr Farahat recalled. “He said: ‘I will make sure you will never, never see the sunlight again.’ I thought it could be true.”

He was put in a cell measuring just five by six metres that contained more than 100 men, mostly suspected of conspiring against the Assad regime.

“I just don’t remember how I survived,” Mr Farahat said, describing horrific conditions during his four-month imprisonment including extreme heat, a lack of water and food, and dire sanitation.

He shared a 30cm by 150cm patch of concrete with a cellmate, taking turns to stand and sleep to gather their strength for endless rounds of questioning and beatings.

The prisoner witnessed seven people die during his detention, hearing tales of many more.

“Some people were beaten to death during interrogation,” Mr Farahat said.

“The torture is to make people confess but it’s also a method of punishment so they will never, ever think of joining the revolution. This has been going on for 40 years in Syria.

“Others died from illness or weakness – a small injury can become life-threatening because of the conditions in the cells and lack of medical supplies.”

The doctor said others succumbed to the extreme conditions, describing watching three men die in front of him after going into seizures brought on by heat and dehydration.

“I would try to help the injured people and knocked on the door asking the guards for medical supplies, or to be allowed to take them outside for fresh air,” Mr Farahat said.

“The guards would come to the bars and tell me: ‘Knock on the door when they die.’ It became a famous saying.”

His account has been echoed by numerous other prisoners, including a man jailed at the Syrian capital’s Military Intelligence Branch 235.

Ziad said dozens of people suffocated to death when a ventilation system stopped working in their cell.

He added: “The guards began to kick us to see who was alive and who wasn’t.

“They told me and the other survivor to stand up - that is when I realised that I had slept next to seven bodies. Then I saw the rest of the bodies in the corridor, around 25 other bodies.“

Detainees reported method of torture including contorting victims’ bodies to fit in a rubber tyre, hanging from the ceiling, burning them with boiling water and cigarettes, or pulling out their nails.

Mr Farahat was eventually moved to another prison in Damascus and tried by a “terrorism court”, which freed him after finding no evidence to support his continued detention.

But he returned to his hospital to be refused work, having been blacklisted by the authorities, and had his dream of qualifying as a paediatrician within months dashed.

While continuing to seek medical work, he was re-arrested with a group of friends in April 2013 as they ate at a restaurant.

Intelligence officers had wanted to detain a friend who worked as a news reporter but imprisoned Mr Farahat again because of his “black file”, starting the cycle of torture once more.

When he was freed for a second time six months later, he received a conscription note for mandatory military service and fled to neighbouring Lebanon illegally to avoid border checks.

“I only told my parents when I had arrived in Lebanon but I wasn’t completely safe because there were spies for the Syrian regime,” he said.

After almost two years in refugee camps, he was selected by the UN Refugee Agency for resettlement in the UK and was moved to Bradford in March 2015.

Having found a job as a teaching assistance at a secondary school in London, he is planning to move to the capital to start work next month.

“I don’t know why I was chosen, I was so happy,” Mr Farahat said, but his relief is tainted with sadness for his hometown in Idlib province, which has been mostly destroyed in the war.

“I don’t know if I will ever be able to go back to Syria,” he added. “It is one of the most difficult questions in my life.”

Both the Damascus and Latakia Military Intelligence branches where Mr Farahat were held were listed by Human Rights Watch as torture centres in a 2012 report.

The group found a “state policy of torture and ill-treatment” that it said amounted to crimes against humanity.

Britain is also among the countries to have imposed military sanctions of Syrian Military Intelligence branches, as well as other officials and departments in President Assad’s regime.

Using the testimony of dozens of torture survivors, Amnesty International has chronicled massacres at facilities including the notorious Saydnaya Military Prison, on the outskirts of Damascus.

One man told researchers a prisoner was forced to rape another man by guards or be killed, while a jailed lawyer said 19 detainees were beaten to death after they were found to be learning martial arts.

“They beat the Kung Fu trainer and five others to death straight away, and then continued on the other 14,” said Salam, a lawyer from Aleppo.

“They all died within a week. We saw the blood coming out of the cell.”

All parties in the ongoing civil war are accused of war crimes, enforced disappearanes, arbitrary detention and torture.

Amnesty International estimates that at least 17,723 people died in custody in Syria between the Arab Spring in March 2011 and December, although the real figure could be far higher as the fates of thousands of people remain unknown.

The group’s Middle East and North Africa Director, Philip Luther, said: “For decades, Syrian government forces have used torture as a means to crush their opponents.

“Today, it is being carried out as part of a systematic and widespread attack directed against anyone suspected of opposing the government in the civilian population and amounts to crimes against humanity.

“The international community, in particular Russia and the USA, which are co-chairing peace talks on Syria, must bring these abuses to the top of the agenda in their discussions with both the authorities and armed groups and press them to end the use of torture and other ill-treatment.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments