‘If they saw us like this, they’d probably shoot us’: Afghan women’s Olympic ambitions are an uphill battle

No Afghan woman has ever won a medal at the Games. Somayeh Gholami hopes to become the first

Five days a week, 25-year-old taekwondo black belt Somayeh Gholami ties her long hair up in a bun, covers it with a white headscarf and spars with her teammates. In her gym, news of suicide attacks in Kabul fades from her mind as she focuses on her only goal: winning at the 2020 Summer Olympics.

Just getting to the games will be an uphill battle. Most Afghan athletes are men, and the country’s few female athletes face some of the most dangerous and restrictive conditions in the world. Now, ongoing talks with the Taliban threaten to further derail their Olympic dreams. Many Afghans fear that if the extremists return to power after 18 years of war, women could again disappear from public life.

On a recent Saturday evening, Gholami looked around the crowded gym in Kabul where her teammates practice alongside their male counterparts. “If they saw us like this, they’d probably shoot us,” she says.

The United States and Taliban have met for several rounds of peace talks since last July. Negotiators have insisted any peace deal with the Taliban will protect women’s rights.

“Afghan women vote and work and got their place in society,” former Afghan president Hamid Karzai, a key voice in talks between the Taliban and Afghan stakeholders, said in an interview at his home in early June. “This is not reversible; this will not go back. The Taliban know this, and we have told them.”

But such promises have done little to lessen concerns among Afghan women, especially athletes. “They will definitely be against sports,” says Samira Asghari, the first Afghan member of the International Olympic Committee. “Maybe they will say girls can go to university, maybe school, but not sports. I’m sure about this.”

Afghanistan first sent athletes to the Olympics in 1936, but women didn’t compete under the Afghan flag until three years after the fall of the Taliban. The IOC banned Afghanistan from participating when the country was under Taliban rule. Since 2004, 13 Afghan athletes have been sent to the Olympics, but just four have been women. In 2008, one female runner fled her training camp and is believed to have sought asylum in Norway before she made it to Beijing.

Over the next year, Gholami and other Afghan athletes will train intensively and compete regionally to try to secure spots at the Summer Games in Tokyo.

Few athletes are more disadvantaged than Afghan women, even in the years since the Taliban was overthrown. Social norms require women to cover their heads and dress conservatively. They are expected to marry young, mother children and prioritise domestic responsibilities. Contact sports such as martial arts or boxing are often considered inappropriate for women; swimming in public is completely out of the question. There are limited athletic facilities, and many families won’t allow their daughters to practice in mixed-gender gyms.

We are a conservative society. In some of our provinces, there are not even places for young boys to go and play.

Athletes are vulnerable to attacks from extremist groups because they buck those norms.

The Olympic facility where athletes now train is home to a soccer field where the Taliban used to perform public executions, including of burqa-clad women accused of adultery, in front of crowds of men.

Hafizullah Wali Rahimi, the country’s top sports official and president of its National Olympic Committee, called the last decade the “worst days of [Afghanistan sports] history”. In recent years, he says, corrupt officials siphoned off resources the Afghan government and its international partners had set aside for women’s sports. A recent sexual abuse scandal on the women’s national soccer team eroded what little trust parents had in sports officials to keep their daughters safe.

As his office attempts to increase women’s participation in sports nationwide, he has had to make careful calculations, introducing low-contact sports like badminton, table tennis and volleyball in girls’ schools to avoid controversy. “We are a conservative society,” Rahimi says. “In some of our provinces, there are not even places for young boys to go and play.”

Gholami might have made it this far in part because she was not raised in Afghanistan.

Her family is from Mazar-e Sharif, in the country’s north, but she grew up a refugee in Iran. Despite being displaced, she sees her upbringing abroad as an advantage; women in Iran move more freely than in Afghanistan and often exercise in public.

If I achieve that goal, I’ll have no more wishes

Eight years ago, she joined a taekwondo club there on a whim. Her lean stature and intense discipline soon made her a natural recruit to Afghanistan’s national team. She still lives in Iran, but travels to and from Kabul for practice. She also managed to balance training and academics, earning a bachelor’s degree in agriculture.

Gholami’s coach thinks she stands a good shot at bringing home a medal if she makes it to Tokyo. She won gold at the 2016 South Asian Games. But her Olympic dreams fizzled that year when she tried to compete in a lower weight class and ended up so weak she failed to qualify. She called it the “biggest mistake” of her career.

Now, her heart is set on 2020. “If I achieve that goal, I’ll have no more wishes,” she said.

Her transition to professional athlete was made easier by her parents, who support her Olympic dreams and allow her to travel regularly for practice and competitions abroad. Other Afghan women are forced to hide the fact they are athletes from their families.

In a run-down gym tucked down a quiet alley in western Kabul one recent afternoon, Sadia Bromand, 23, changes out of her street clothes and into long black leggings, basketball shorts and a black headscarf. Then she wraps her hands and slides on her red boxing gloves. She spends half her week boxing with her coach in this gym, and the rest training at the national Olympic facilities in Kabul. A former sprinter, she hoped to qualify for the 2016 games but was asked to coach a teammate instead. So she switched to boxing, hoping she would make it in 2020. Then her parents found out.

As a sports reporter and avid runner, Bromand had already defied some societal expectations of Afghan women. But her parents saw boxing as one step too far.

“It was like they were in flames,” she says. They worried she would get hurt, be considered unmarriageable, or worse, that the Taliban would track her down and kill her.

Now she keeps her practice routine secret from most of her family, but she says even the national boxing federation doesn’t offer enough support for her to have a fair shot at qualifying for 2020. Federation president Shikeb Satari says Bromand works hard, but as a relative newcomer to the sport, doesn’t have a realistic shot at the Olympics. But Bromand won’t give up.

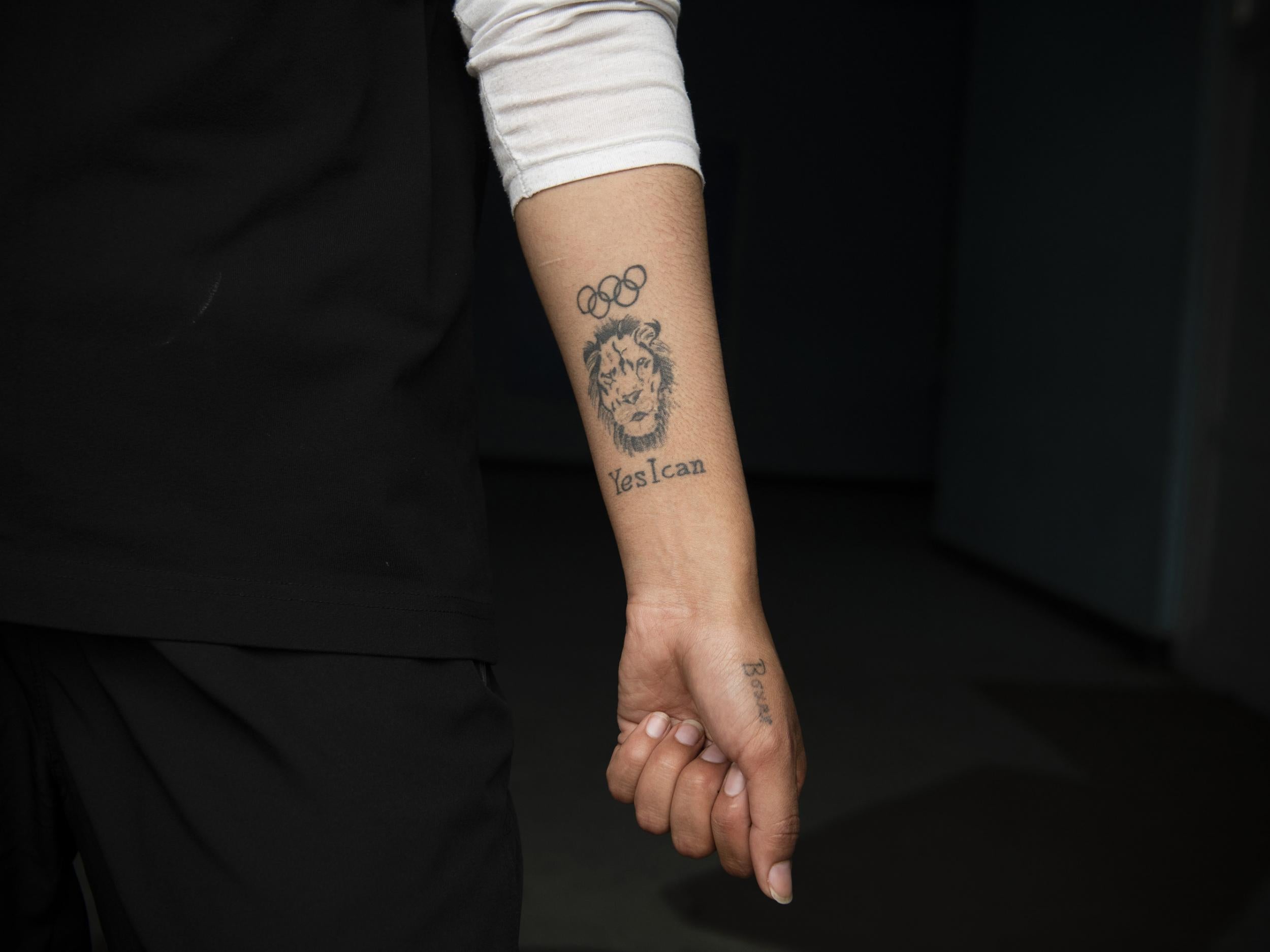

“My life has been much more difficult outside the ring than inside the ring,” she says. “My whole life has been fighting.” When she feels discouraged, she looks at the tattoos etched into her skin that remind her of what she’s working towards. On her right arm: “nothing is impossible”. On her left are the five Olympic rings, accompanied by three simple words: “Yes I can.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks