Nobel Peace Prize: What Barack Obama's role in the Kunduz bombing means for the world’s most conflicted prize

The President's forces are being investigated for an unprovoked attack on a fellow laureate – which is a first

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.What is the point of the Nobel Peace Prize? Should the winner be someone we have all heard of? Should you have to give it back if you start blowing up other Nobel Peace Prize winners?

These are pressing questions this weekend as the world gets to know this year’s surprising winners and President Barack Obama’s forces are investigated for an unprovoked attack on a fellow laureate – which is a first, even in the long, strange history of the world’s most conflicted prize.

“We send a message to the world that peaceful negotiations, consensus, is the best way of taking care of a country’s people,” said the secretive panel of Norwegian judges when awarding the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize on Friday. The winner was National Dialogue Quartet of Tunisia, which sounds like a cool jazz band but is actually an alliance of lawyers, trade unions and human-rights activists credited with saving its country from civil war.

“The message is clear and we hope everybody will listen,” said Nobel judges. But they need to tell that to President Obama, who won his Nobel Peace Prize back in 2009 after just nine months in office. (Nobody was quite sure why, as his country was waging two wars at the time. “Even many of Obama’s supporters believed that the prize was a mistake,” said the secretary of the committee that chose him.)

Obama is commander-in-chief of the US military and therefore ultimately responsible for the AC-130 gunship that repeatedly bombed and strafed a field hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, a week ago.

Weirdly, the aircraft was almost certainly using a 40mm cannon made by Bofors, a company that was once owned by Alfred Nobel, the founder of the peace prize.

Two dozen people were killed, including three children. Among the adults were the staff and patients of the charity that runs the hospital, Médecins Sans Frontières. Doctors Without Borders, as it is also known, was given the Nobel in 1999 for its “pioneering humanitarian work on several continents”.

So a Nobel Peace Prize-winning President is being condemned for sending a gunship to kill the staff of a Nobel Peace Prize-winning charity using weapons made by the company that the founder of the Nobel Peace Prize used to own.

President Obama rang the head of MSF to apologise personally for the attack, which he said was a tragic accident. Dr Joanne Liu was not satisfied with the apology and is calling for the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission to “establish what happened in Kunduz, how it happened, and why it happened”.

Unfortunately, that’s not the way the American war machine works. It prefers to carry out its own investigations, shrouded in a secrecy rivalled only by the way the winner of the Nobel Peace Prize is chosen.

The five men and women selected by the Norwegian government always describe their decision as unanimous. If they fall out, throw kjottboller at each other or get blasted on aquavit together, they don’t say so.

Looking up at the gold and cream façade of the Nobel Peace Center, darkened by the rain on the waterfront in a gloomy Oslo, I wonder what it is they are trying to achieve. This is a surprisingly modest building for a prize whose organisers insist on calling it the most prestigious in the world. The former railway station has twin square towers and an oversized version of the gold medal stuck high over the entrance, carrying the face of Alfred Nobel.

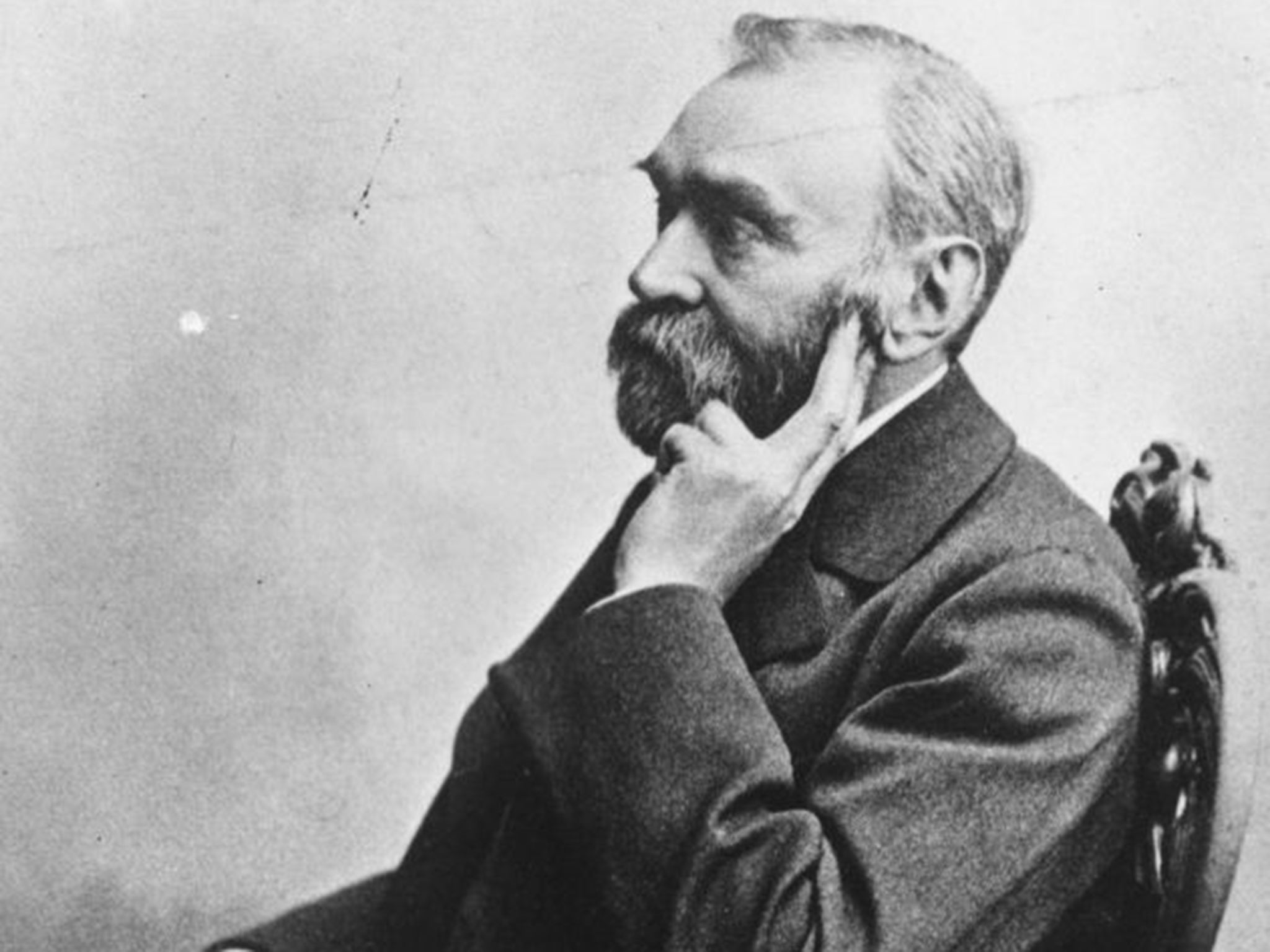

He died after a stroke in 1896 and left a huge fortune to be used to establish awards to celebrate medicine, chemistry, physics and literature. Those seem fairly straightforward and understandable, but his motives for establishing a peace prize are mysterious. Some say it was guilt, as the inventor of dynamite and several other forms of explosive had made a fortune as an arms manufacturer, with factories all over Europe including those in the name of Bofors.

But he was no pacifist. Nobel was an early adopter of what leaders in the nuclear age would know as mutually assured destruction: “When two armies of equal strength can annihilate each other in an instant, then all civilised nations will retreat and disband their troops.”

His prize has often seemed as conflicted as he was. How, after all, do you define a champion of peace?

Henry Kissinger was given a Nobel his for efforts in Vietnam in 1973, but the war continued for another two years. He was implicated in propping up violent right-wing regimes in South America as well as bombing Cambodia. “Political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize,” said Tom Lehrer.

Other laureates have gone back to war with each other after sharing a prize, including the leaders of Israel and Palestine after winning in 1994. But the attack on the hospital puts Obama in a different category.

Can the prize be revoked? “No,” said Geir Lundestad, former secretary of the Norwegian committee, in a startlingly abrupt interview made public by the Nobel Foundation last year.

Asked if he regretted any of the prizes given during his time in office he said, “No comment.” Had Obama been a good choice? “The committee certainly thinks so.” Could the committee ever give in to the strong opinions of those who want to see Obama lose his prize? “No.” Asked to explain what the members of the committee do if they disagree, he said, “No, that is secret.”

So who are these people? The formidable woman in the salmon pink jacket who made the announcement on Friday, behind a lectern that looked like a witness stand, was the chair of the committee, Kaci Kullmann Five.

Her name also sounds like a jazz band, if you say it wrong. She is a public affairs adviser and former chair of the Conservative Party of Norway.

The two other women and two men on the board include a senior lawyer, a political adviser to the Progress Party, and the Secretary General of the Council of Europe. There is also an academic from the Peace Research Institute in Oslo.

They are mostly politicians. This is a closed world. You have to be a former winner to nominate a candidate, or a member of a national assembly or the courts at The Hague; a professor of history, social sciences, philosophy, law or theology; a university president; or the director of an international affairs or peace research institute.

Nominations are not made public for 50 years, which can be a good thing. Hitler was nominated by a member of the Swedish parliament in 1939, as a satire on his colleagues nominating Neville Chamberlain.

Stalin was nominated in 1945 and 1948 for his efforts to end the war.

Political satire became obsolete when Henry Kissinger was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

Gandhi was nominated five times, including the year of his assassination, 1948. The prize was not awarded that year because there was “no suitable living candidate”.

Sometimes there is general acclaim for the choice, as with Nelson Mandela or Martin Luther King. You could say the same about Malala Yousafzai, who overcame an attack by the Taliban to become an advocate of the rights of girls.

But some argue it was too soon for her. And how many remember the name of the man she shared the prize with last year? Kailash Satyarthi has campaigned to get children out of slave labour and into school for many of his 61 years.

This year, the bookies’ favourite was Angela Merkel, for her handling of the refugee crisis. John Kerry and his Iranian counterpart Mohammad Javad Zarif were also fancied, for the remarkable deal they brokered on nuclear power.

The Pope was left empty handed despite the palpable excitement in the Vatican, according to one eyewitness in the press room there: “If the density of waiting journalists per square metre is anything to go by, Francis is a shoo-in.”

Not true, as it turned out.

Sometimes the winner is completely taken by surprise, as Mairead Corrigan Maguire was when she won in 1976 with Betty Williams. They were co-founders of the campaign and support group Women for Peace in Northern Ireland.

“I cried because I really felt very frightened. I didn’t know how to cope with the Nobel Peace Prize. I was a very ordinary young woman living in a community,” she said. “All of a sudden the world’s press landed in the Peace House and I was being asked big questions like, ‘How do you get world peace?’ What did I know about getting world peace?”

She had become a campaigner after the three children of her sister Anne were killed by a car driven by a member of the Provisional IRA, as he fled the British Army. Grief and rage turned into action then, just as fear did now.

“Gradually I overcame that fear and began to accept and enjoy and love the privilege of being able to carry the Nobel Prize and use it for others,” said Mrs Corrigan Maguire, who has since supported Wikileaks and the Occupy movement, been arrested outside the White House and turned down a Nobel gathering in Chicago in 2012 because it was hosted by the US State Department.

“To me, the Nobel Peace laureates should not be hosted by a State Department that is continuing with war, removing basic civil liberties and human rights and international law and then talking about peace to young people,” she said. “That’s a double standard.”

That’s also life, the founder of the peace prize would probably say. Since 1901, it has been meant for the person who “shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses”.

It was never meant to be a democratic process. If you gave the world a vote, you would get a different result. (“And the Nobel Peace Prize for this year goes to … One Direction.”)

Nobel didn’t trust the Swedes, who he thought were too militarist to run this one. Instead, the self-styled greatest prize on earth is given away by a tiny huddle of serious middle-aged Norwegian committee men and women trying to live up to the ideals of a highly contradictory arms dealer-cum-peace campaigner who died more than a century ago.

This year they gave the prize to a committee. People just like them, then. That’s not very sexy.

But the Quartet has kept a country from tragedy and Mohamed Fadhel Mahfoudh, president of the Tunisian Order of Lawyers, says the award encourages people who are using words to fight for their lives. “Everything can be solved in a peaceful climate. To engage with weapons does not lead anywhere.”

That’s what the Nobel Peace Prize is for, then, in its own idiosyncratic way. To send that message. This year, at least.

Now all they have to do is tell Barack Obama to give his medal back.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments