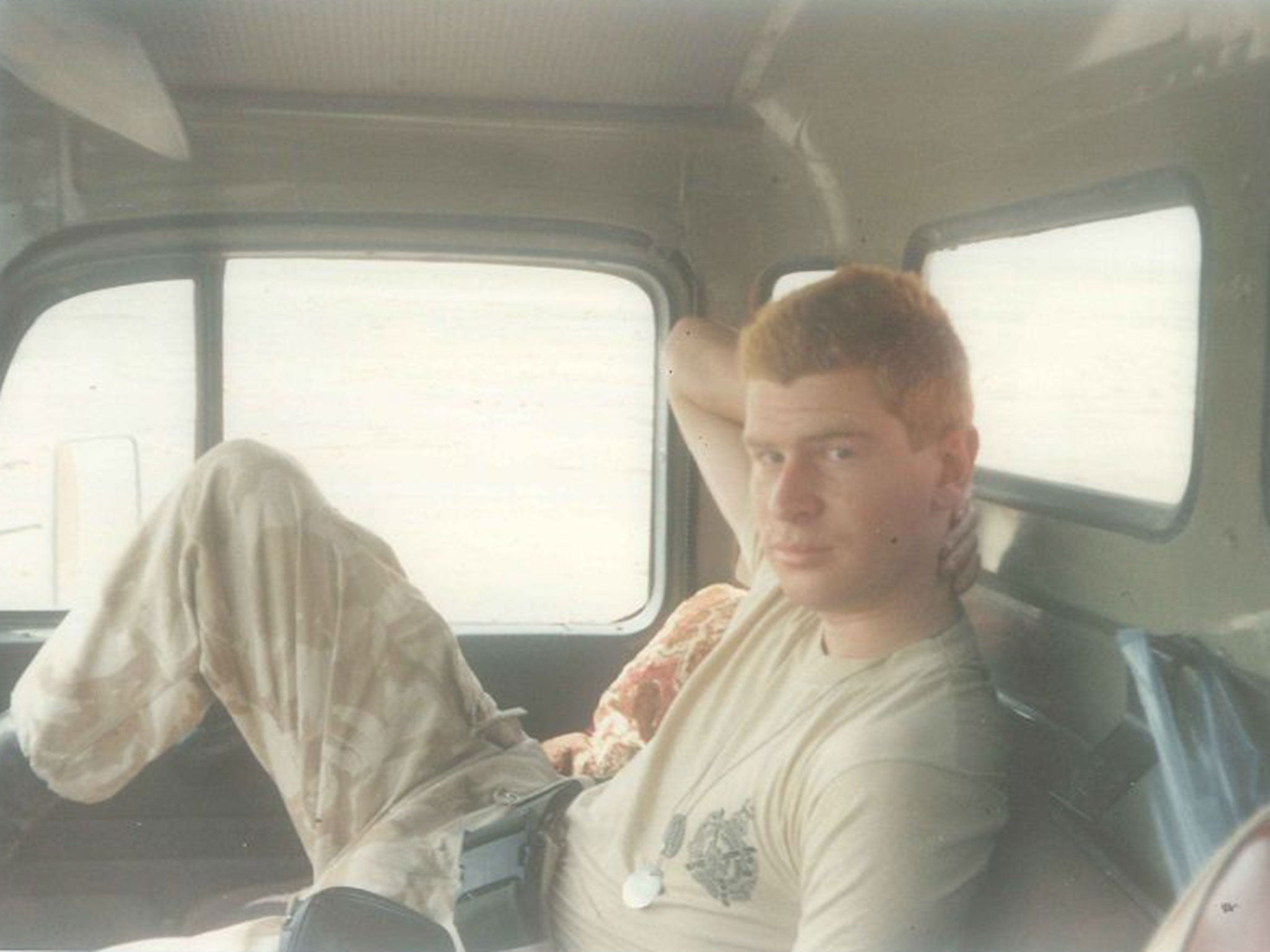

My Gulf War: William Wright's diary shows how an ordinary soldier coped in the midst of Desert Storm

Twenty-five years ago this weekend, the first Gulf War was declared against the Iraqi invaders of Kuwait. William Wright, who was keeping a journal about army life, arrived in Saudi Arabia soon after. These extracts – as much about duty as heroics – reveal the role played by ordinary men in an extraordinary situation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.2 January 1991

On leave in Folkestone

Late this afternoon I received the phone call. My heart skipped a beat and my legs turned to jelly as the voice told me that Granby had been called. [Operation Granby was the British name for the build-up to the Gulf War; however, it was to be more commonly known by the American assignation of Desert Storm.]

30 January

Rezayat Camp, Saudi Arabia

After passing through Jubail, we collected our Bergens [rucksacks], weapons and kitbags, and were shown to our accommodation. We're going to be living in a two-man Portakabin with a bunk-bed, sink, toilet and shower (all the mod cons).

31 January

We were told one of our duties will be prisoner escort, which will inevitably take us to the front line and lead to possible action. My hair stood on end and I had a huge knot in my stomach.

1 February

I'm going to have to be pretty careful in the sun, as I burn very easily and it's something I don't fancy being charged with. [Army regulations state that anyone who goes sick or cannot carry out normal duties because of sunburn will be charged with causing a self-inflicted wound.]

2 February

Training at Devil Dog Dragoon Ranges, Saudi Arabia

Ah, the nice morning wake-up call of "Move your f**king arses!" We had our kit checked and our weapons inspected, sat around for a bit and had another weapons inspection followed by a kit check. Then we got on parade and waited for the transport with more checks and inspections thrown in. When it arrived, we all rushed to the buses trying to get a seat by the windows.

It was my first real sight of the countryside – how vast it all seemed, one long road sandwiched by hundreds of miles of sand – and during the journey I noticed a couple of dead camels lying by the roadside. I remember thinking that they were probably as common as cats back in the UK.

Following a drive of about 2½ hours we stopped. After carrying out 5-metre and 20-metre checks to make sure our harbour area was safe to move into, we got our kit together and walked in. (A harbour area is a place where we dig in, so that we can carry out our reconnaissance missions. It's also a place from where we can attack, and be safe from attack, and where we can sleep, eat and rest.)

On our way in, I glimpsed my first desert wildlife, a sand viper, which was curled up sleeping; and scurrying about in the sand were a few dung beetles. I couldn't get over the size of them. Soon darkness fell and looking about the desert there was nothing to see but a black mass: no buildings or trees in the distance, no street lights nor any sign of life. The only thing I could see were a couple of oil platforms glowing some way off, but I couldn't even begin to work out how far away they were.

At 20.00hrs we were called for scoff – and if you've ever wondered why the Army calls it "rations", you'd have known if you'd been there. There was hardly enough on my mess tin to feed a sparrow. (The Army marches on its stomach? My arse.) Once I'd was back in my trench, I grabbed some sleep before going on stag [guard duty], and you could feel the bite of night. You read about how it suddenly gets really cold; well, now I know it's true.

9 February,

Rezayat Camp

Up early, we drove out into the desert for about two kilometres, de-bussed and adopted all-round defence positions (whereby everyone lies down in a huge circle facing outwards). After about 20 minutes, we were up and patrolling into our harbour area. Sean and I were dropped off in our position, dumped our kit behind us and began to dig our shell scrape [dugout].

Then we set about cleaning our weapons, but the wind was blowing the powdery sand all over the place. Sean's weapon was covered, and he was having difficulty in getting it back together again. He was getting more and more annoyed with himself and I couldn't help but laugh, which made him worse; and the worse he got, the more I laughed. Suddenly someone started shouting "Gas, gas, gas!" Oh shit.

I took a deep breath, closed my eyes, got my respirator out of its pouch and put it on. The quicker you can do this the better – 10 seconds is the ideal – and once it has been correctly fitted, you must blow out hard and fast, expelling any gas that may be trapped, before shouting "Gas, gas, gas!" as loud as you can, both for people who didn't hear the original call and for those around you, so they know you haven't been affected and are alert to what's going on.

Next comes the chemical protection suit, consisting of jacket (smock), trousers, rubber boots that fit over your combat boots, and two pairs of gloves made of thick rubber. Jesus wept, I was sitting in an oven and the heat was unbearable, almost suffocating. It's very easy to panic when you're cooped up like that: the sweat was pouring out of me – I could feel it trickling down my back – and there was no air getting in anywhere.

I was covered from my rubber boots to the tight-fitting hood on my head. The only thing you could do was sit down and try not to move too much. I noticed Sean starting to fall asleep, and it wasn't long before I joined him, waking up every time my head fell.

I was starting to suffer now: the respirator straps were cutting into my head, which caused a throbbing pain, and I couldn't breathe properly. I was at breaking point, and I put my hand under my hood to loosen the strap – oh, bollocks, no one was watching – and grab myself some air. [It had become apparent by now that this was a training exercise.] The coolness as it rushed in was so refreshing that if this happens for real I am going to die. After a while we were given the all-clear. I jumped to my feet and pulled that kit away from me, taking in deep breaths. My combats were soaking with sweat, but it was so good to feel the air about my body again.

15 February

We are to be taught some basic Arabic phrases, but I don't think we'll be practicing them downtown. (I don't suppose we'd get a very friendly reception from the storekeeper by telling him to shut up and put his hands on his head.) And we've been given the news we'd been dreading: we'll be moving up north to the frontline on Tuesday.

18 February

We're off to Wadi Al Batin tomorrow, about 20km from the Kuwaiti border. I phoned Mum to let her know they were pushing us towards the front line. She sounded worried and I tried to reassure her – but then again, I didn't know what to expect myself. I then joined the queue again, so that I could phone [my then-partner] Carole; she got a bit upset and I calmed her as best I could.

19 February

Kuwaiti desert

As soon as we landed we were told of plan changes, which didn't surprise anyone. Instead we're going to Maryhill, our main POW holding area – which we realised on arrival was just a few tents and a field kitchen surrounded by masses of barbed wire.

22 February

While standing in the trench during my time on stag I could see the night sky lighting up in the distance, followed by a faint bang, as well as dotted lines of red tracer being fired into the sky. I knew Iraq was under attack and hoped it wouldn't be long before they surrendered.

26 February,

Iraqi desert

"De-bus, de-bus!" someone was shouting. "Take up all-round defence positions. Spread out, come on, move your f**king arses."

Four of us ran about 20-25 metres from the truck and found ourselves a position. My heart was beating and my mouth was dry. My eyes were wide open and continually scanning. As I looked back to my right, I saw a horde of Iraqi troops walking towards our trucks with their hands above their heads. After everything was cleared, we put them all over the vehicles – we even had them sitting on the fronts of Land Rovers – and I couldn't help but feel sorry for them: they were in absolute shite order. Apparently they had been in their trenches for over a week without proper food or water. I'm hungry, but it's nothing compared to what these guys are going through.

27 February

Four buses arrived for the POWs. We transferred them to an American holding area, where we managed to scrounge some MREs (meals ready to eat). You could tell they were American rations, with their chocolate muffins and hash browns: not too practical, but still tasty. Soon we were off trying to catch up with the rest of the battalion, and on our way we saw a few Iraqi bodies propped up against sandbanks (the first I'd ever seen). Further out and the remains of war were obvious: Iraqi tanks and vehicles lay burning or burnt out, smoke rising. When we caught up with the battalion, it had stopped right beside a minefield. Once I came off stags, I got two letters, but I was too tired to read them and put them in my pocket for the morning.

28 February

A ceasefire has been called, albeit unsteady. I just hope it lasts the pace, not for our sake but for theirs. We must have captured half their army and the amount of armoured personnel carriers I've seen burnt out, they can't have much to fight with.

1 March

We travelled through the night, and I tried to get as much sleep as I could but I was in a pretty uncomfortable position. We eventually arrived at our destination and began to set up a holding area. We dug shell scrapes on the four corners of our compound and faced inwards, watching the POWs cautiously. We've got about 250 but they're proving no problem; I think they're very happy to be out of the war, and at least they're being fed.

2 March

As I was standing at the back of the POWs, one of them turned to me, saying, "Mister, mister," and pointing from his stomach to his arse. I waved my weapon in the direction for him to move, and we got to a small bush, where he crouched down and started shitting. The smell hit me and I started gagging. I didn't want anyone seeing that it had nearly made me sick, so I quickly ushered him back to his position. There are rumours going around that we could be out of here by the end of April. Well, unless I have to escort another Iraqi for a shit, I won't hold my breath. About 200 metres away a Chinook has dropped off sacks full of mail. I must get at least get one letter from that lot.

3 March

A trip to look at abandoned Iraqi bunkers and vehicles. They'd been quite well dug in, and they left a lot of kit: tin bins [helmets], water bottles, respirators, a lot of ammunition.

4 March

After Dixie [pot-washing duty], something each platoon takes in turn, I caught up with letter writing, telling everybody about our exciting Desert Storm – well, in reality more a quiet storm – and I dared to take my top off. It's embarrassing enough going back to the UK having done nothing – but to go back white? Well, that's not even worth thinking about.

As I was writing, someone tapped me on the shoulder and I was confronted by the charred remains of an Iraqi foot. "Ah, f**k off, you sick bastard!" I shouted.

One of the corporals was going round kicking people's faces with this foot, and I had a nauseous feeling at the pit of my stomach. The realisation hit me: that used to be a person, someone's son. I was overwhelmed by a feeling of sadness and guilt, it was horrible.

11 March,

Saudi desert

Our days are spent sorting out personal kit, letter writing and playing cards. The highlight has been a TV and video, set up off a generator by the Colour Sergeant, so we were able to watch Rocky V and Another 48 Hours. We were also able to drive to a local camp and have our first real shower since leaving Jubail. Don't get me wrong, we did have showers using the buddy system – which involved one guy standing in a plastic basin and the other pouring water over him – but if you've got a problem with shyness then you're gonna stink.

12 March

We were able to use an R&R centre, but I only went once, as it was absolutely shite. I received a couple of parcels – Carole had sent me a Walkman and some tapes – so I found it more productive to listen to that while sunbathing and writing letters.

Alan Mullholland came up to me clutching a newspaper and pointing to a photograph. "You were at the depot with him, weren't you?" I looked at the face and recognised Clarke Ferguson. "He's been killed by ["friendly fire" from] the Yanks" said Alan. Goosebumps appeared all over my body, and I felt the hair on the back of my neck stand on end. For one sad moment, the reality hit home. As I read the article, I discovered it was Martin, Ferguson's twin brother. I remember him telling me he had a twin brother – but my God, they were so alike.

3 April,

Camp Ventura, Saudi Arabia

The first time we've been in a proper camp since 19 February. Next we're moving up Kuwait. Apparently, it's in a real mess, needs sorting out and we're the ones to lend a hand.

4 April,

Kuwait City

We landed in at 10.00hrs, and it was my first sight of the war-torn city. The airport had seen better days – potholes in parts of the runways – and the once-smooth buildings were now peppered with bullet holes. I was sitting at the back of the Bedford, which enabled me to have a good look at the pathetic looking city. Burnt out vehicles, cars and trucks had been upturned, and the sky was black from the smoke of the burning oil wells.

We all jumped as we heard the sound of an explosion 4km away. We arrived at Ibby camp, which had been occupied by Iraqi troops, and the mess was unbelievable. Books, clothes and children's toys were strewn all over the camp. It once housed expats, and they'd had to flee quickly, taking only bare essentials.

Postscript

The time came to leave our desert home, and the excitement was incredible, the atmosphere electrifying. Still, we had rigorous kit-checks – to make sure no one had any illegal Iraqi souvenirs such as ammunition or weapons – before we loaded it onto the planes.

A huge emotion welled up inside me as we touched down. I made my way into the terminal to collect my Bergen and kit bag, and out into the waiting-area which was packed with family, friends, TV cameras and reporters. I pushed my way through, all the while trying to catch a glimpse of Carole's face. I waited on the path for about five minutes, next to the buses laid on for us, until I realised no one had come to greet me. I got on and sat near the back, with a huge lump in my throat as I watched the happy reunions outside...

It turns out it wasn't Carole's fault. There are two Wrights in the battalion and someone had told her I was on the second plane. The daft bastard.

To learn more about the Gulf War, visit iwm.org.uk/history/what-was-the-gulf-war

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments