Iran's revolutionaries, masters of chaos and crisis, mark 40 years of the Islamic Republic

How Iran 'mastered the art of using and abusing external pressure and crises to create a rally-round-the-flag effect'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few believed a bunch of loud, unruly Islamists and leftist zealots could seize control of what was then one of the most powerful countries in the world. Western intelligence agencies wrote off the revolutionaries taking on the forces of a two-millennia-old monarchy as a bunch of graduate students in slippers.

And once the revolution was declared victorious, fewer still believed it would survive more than a few months. Iranians in exile and western leaders have been predicting its demise for decades. Donald Trump’s national security adviser, John Bolton, predicted last year the Islamic revolution would not celebrate its 40th birthday.

But the Islamic Republic of Iran remains, and is in many ways stronger than it has ever been. It has weathered numerous agonising domestic and international crises, including war, domestic upheaval, and global isolation.

Yet it finds itself among the most stable countries in the Middle East. Far from being contained by its enemies, it has positioned proxies around the Middle East, cultivated allies and friends in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, and counts UN Security Council superpowers Russia and China as patrons.

“Iran’s current role in the region is more important than at any other point in history,” Iran’s president Hassan Rouhani told tens of thousands attending the annual commemoration on the 22nd day of the Persian month of Bahman in Tehran on Monday.

“Any country and any superpower are free to say anything they want, but Iran is the only country that can help regional nations if they want security,” he said. “Without Iran, no plan can be implemented in the region.”

The Islamic Republic not only survives, it has become a force to be reckoned with throughout the region, through allies in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, and clandestine networks stretching from south Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, and north Africa to Europe and Latin America.

But the country is also deeply troubled, and its leaders know it. The country’s youth, women, and minorities are demanding systemic change.

They want jobs, social freedoms, and cultural and political rights. Yet the regime’s 40-year survival, experts say, is due in large part to the very repression and vigilant surveillance that so rankle Iranians who belong to social and political tribes outside of the circle of hardline Shia Islamists that monopolise political power.

“The regime of the Islamic Republic was able to endure because it was able to maintain the ideological integrity of its elites, through processes of political and ideological vetting,” says Tamer Badawi, an Iran expert at the European University Institute, a think tank based in Italy.

“This prevented outside powers from creating coalitions with institutional players in the establishment.”

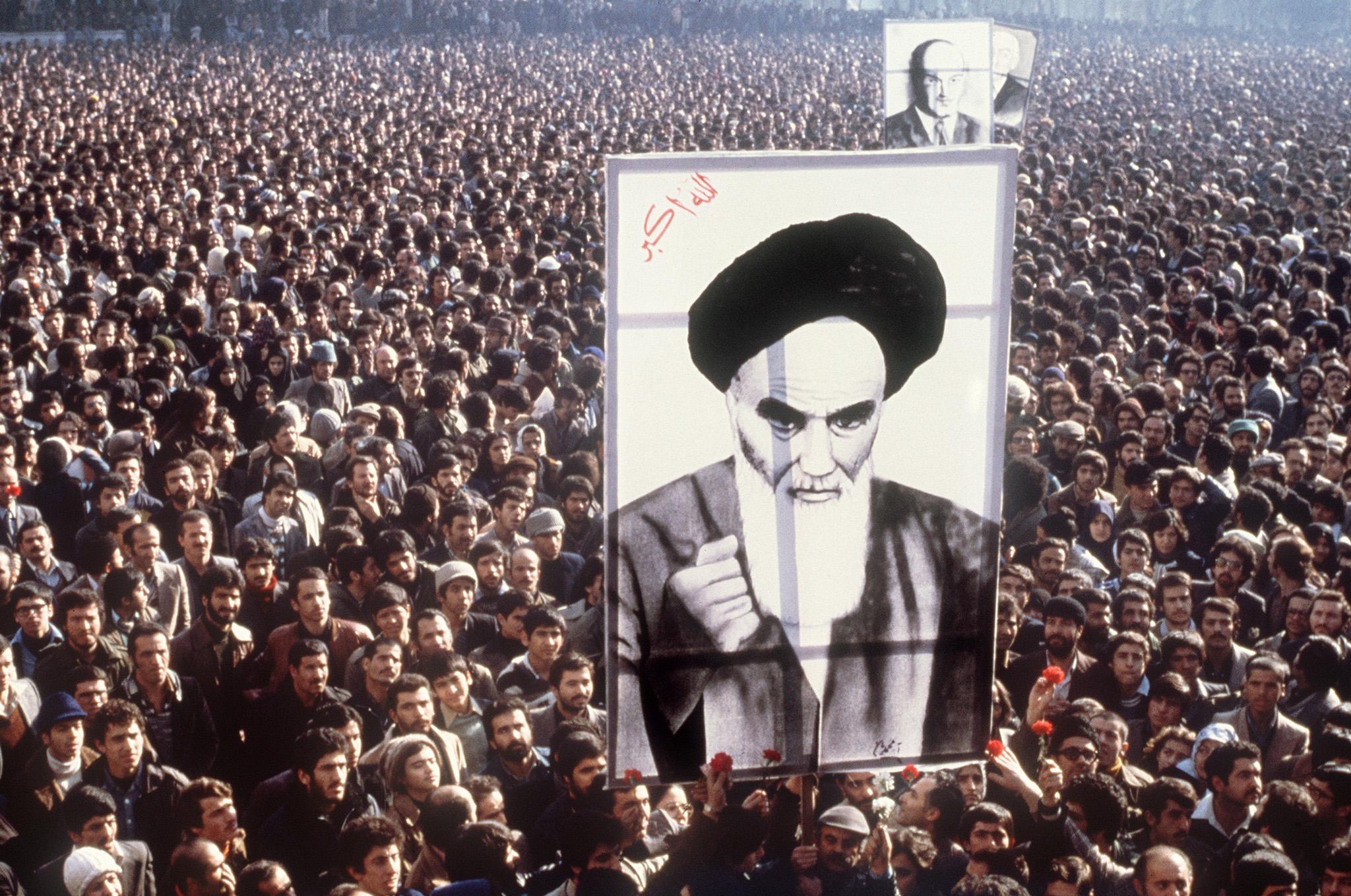

With a white beard and a black turban, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini arrived on an plane from France on 1 February 1979, setting himself up – with the help of fervent supporters – in what had been a girls’ school called Refah in an alleyway in downtown Tehran. He conferred with activists and dignitaries crowding in to see him and hear his words over 10 days.

And then, on this day 40 years ago, Ayatollah Khomeini declared the end of thousands of years of Iranian monarchy, marking the official victory of the Islamic Revolution, and raising hopes among Iranians for a future of peace, prosperity and justice.

But hopes for the future were dashed almost straight away. The fledgling regime shock troops began a long, dreadful night of Robespierrean terror almost straight away, launching purges and mass executions of political rivals and members of the former regime.

Islamist thugs knifed women at protests against the now mandatory hijab. Newly established Islamist courts began enforcing strict restrictions on press, politics, and religion. A vast terrifying surveillance state spread its tentacles into streets, universities, workplaces, and even homes.

Those deemed insufficiently loyal to the new regime were purged, warehoused in prisons like the notorious compound in Tehran’s Evin district, and hounded into exile.

The regime viciously targeted the country’s once thriving Baha’i religious minority, feminists, leftists, and liberals, storming into their homes in the dead of night.

Ayatollah Khomeini eventually was moved to a compound in the north of Tehran, and the Refah school became a torture chamber where perceived opponents were shot dead on its roof.

The regime encountered severe resistance from Iranians from the start, but managed to hold together thanks to a series of crises that kept the ruling elite united, and bound the society to the state.

First came the burdens of a devastating eight-year war with Iraq that continue to haunt the country. Saddam Hussein’s troops invaded, backed by Persian Gulf countries and eventually the west. Rockets rained down upon Iranian cities.

Then came numerous rounds of harsh international sanctions led by the US under seven American presidents, but joined occasionally by many other nations as well as private companies who stay away from the Islamic Republic.

Several popular uprisings have come and gone, including one almost 10 years ago that saw millions flooding into the streets in scenes reminiscent of the revolution itself.

Perhaps the biggest challenge came from within its own ranks. A group of regime loyalists who once called themselves the “Followers of the Line of the Imam” began to sour on the failed promises of the regime and increasing power of the most radical hardline factions. They rebranded themselves reformists in the 1990s and sought to cultivate support among middle-class Iranians.

Over the years the regime learned to adapt and exploit the pressure for its own ends. Ali Fathollah Nejad, an Iran scholar at the Brookings Doha Centre, describes how successive waves of pressure that many predicted would lead to the regime’s downfall instead strengthened it.

“Since its inception, the new rulers have willfully mastered the art of using and abusing external pressure and crises to create a rally-round-the-flag effect centered around the narrative of Iran being an innocent victim in the face of unjustified and abusive imperialist powers, and to engage in disavowing and cracking down on internal dissenters portrayed as stooges of malign outside forces,” he says.

To create and win loyal constituencies, the Islamic Republic cultivated middle classes through a web of institutional vehicles through which it disseminated its revolutionary ideology

But in addition to repression, it sought to create its own educated elite, and even bind the old intelligentsia to the current system. It expanded literacy, higher education, healthcare, and electrification, and invested in the provinces.

“To create and win loyal constituencies, the Islamic Republic cultivated middle classes through a web of institutional vehicles through which it disseminated its revolutionary ideology,” says Mr Badawi. “Urbanisation was one of the reasons for the loyalty of new stratas originating from Iran’s rural spaces.”

But the conservative clergy and military hardliners that make up the inner circle of the regime have also been blessed with an opposition that was divided and fragmented.

“It’s a regime that’s very much aware of the dynamic nature of Iranian society and it managed to exploit that dynamic,” says Sanam Vakil, an Iran expert at Chatham House.

“There’s not been a history of social cohesion in Iran, and Iranians are not particularly united in what they want, even if they’re relatively united in what they don’t want.”

“Allahu akbar,” the cries from the rooftops rang out at night almost 10 years ago, when huge segments of the Iranian population flooded into the streets to oppose the reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad amid fraud allegations, sometimes coopting slogans and tactics of the revolutionaries 30 years earlier.

The millions included members of the Islamic Republic’s own elite, the sons and daughters of politicians and judges, and they marched with defiant slogans near Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s headquarters in Tehran, giving the the system’s guardians the fright of their life.

As the 2009 uprising as well as the nationwide demonstrations last year showed, even beneficiaries of the Islamic Republic have begun to bristle at its restrictions and failures, at its unfulfilled promises of freedom from tyranny as well as its inability to deliver economic prosperity. The regime managed to fend off the massive 2009 challenge, and easily suppressed the protests last year.

Some segments of Iran’s younger generation are disillusioned with the regime and remain hopeful that change is on the horizon

But discontent continues to run wide and deep. A survey conducted in December by IranPoll of 1,000 Iranians showed more than 70 per cent believe the economy is faring poorly, and nearly 65 per cent think it is getting worse.

Almost 60 per cent blame government incompetence and corruption as the primary cause of the poor economy rather than US sanctions.

For now, the hardliners retain a tight grip on the security apparatuses, judiciary, and key segments of the economy. But reformists and moderates win election after election.

A note issued on Monday by the Soufan Group, an intelligence and security consultancy, said: “Even though Ayatollah Khomeini’s revolutionary vision remains popular with the old guard, allowing his successor to maintain a firm hold on power, some segments of Iran’s younger generation are disillusioned with the regime and remain hopeful that change is on the horizon.”

Although it falters on the economy and providing hope to the young, the Islamic Republic has scored historic strategic victories abroad in recent years. It has bolstered its influence in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Yemen.

Washington conservatives say Iran’s foreign policy ambitions are rooted in the ideology of the regime. But time after time, Iran has exploited the mistakes of its adversaries, suggesting an opportunistic power aiming to expand Iran’s national influence, often with tools other than raw military power.

In the aftermath of the US abandonment of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, Tehran opted to stay in the agreement, making Washington look like the outlier, and prompting a rift between America and Europe.

“Iran’s diplomacy has proved deft, particularly in response to the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal and related attempts to isolate Iran politically,” said the Soufan Group note. “Iran has continued to adhere to the agreement, using that compliance as leverage to compel the European Union countries to defy US pressure to enforce reimposed sanctions on Iran.”

Considered the most objectionable dimension of the Islamic Republic, Iran’s foreign policy and defence advances have yielded a domestic political dividend in a country that is becoming increasingly nationalistic, and sensitive to threats from abroad as a result of the Iran-Iraq war.

We have not asked and will not ask anyone permission to build different types of anti-armour missiles, air defence, surface-to-sea, sea-to-sea, air-to-air and surface-to-surface missiles

The US, EU, Saudi Arabia, and Israel have demanded that Iran roll back its support for militant groups across the Middle East, stop refining its missile programmes, and maintain restrictions on its nuclear programme.

But in the IranPoll findings, 86 per cent of respondents said the country should either maintain or increase the support it gives to armed groups fighting “terrorist groups like Isis”. Around 90 per cent said it was important to pursue nuclear technology. And 95 per cent said they supported the country’s development of missiles.

In his speech from the podium on Monday, Mr Rouhani boasted that Iran’s military-technological developments have stunned the world, increasing dramatically in particular during his five years as president.

“We have not asked and will not ask anyone permission to build different types of anti-armour missiles, air defence, surface-to-sea, sea-to-sea, air-to-air and surface-to-surface missiles,” he said. “We will continue our path and our military power.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments