Water Wars: Drought drove people into the arms of Isis, and it could happen again

Water shortages helped jihadis recruit members to their ranks in the past. Now the same problems, if left unchecked, could once more bring unrest to northern Iraq, Bel Trew reports in the fourth part of this series

Black-clad fighters promised the group of penniless Iraqi farmers together they would conquer “all the lands to Burma”. The attentive teenagers from al-Jazirah, an area west of Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown, did not know where Burma was but it sounded far away.

After years of punishing droughts, which had blasted their lands and livelihoods, they did not really care. Their real interest was in the salaries of more than $400 a month.

This was early 2014. But for years, residents of this area and others in Iraq’s northern Saladin governorate had noticed strange men in religious garb visiting the rural areas during difficult farming seasons. It seemed that whenever the droughts struck the visitors would appear, sometimes dishing out food, sometimes money, sometimes agricultural supplies.

In the early days these men, part of what would later morph into the Islamic State, tried to stoke local anger by accusing Iraq’s Shia-dominated authorities of deliberately ignoring the embattled Sunni areas. They even claimed there was a government plot to halt river flow to worsen the water, and so farming, crisis.

Few had paid that much attention. However, people began to listen in the spring of 2014, when Isis was fast advancing through northern Iraq, unfurling a territory and brutal regime that stretched deep into Syria.

Nawaf, 27, a farmer who lived under the caliphate and watched with horror as people signed up, says the jihadis homed in on the most vulnerable farmers of fighting age, around 18 and 19.

“They promised them they would become emirs [princes] and governors. They lured them in with the salaries, they told them they would conquer all the lands to Burma,” Nawaf tells The Independent from his village al-Aly, east of Tikrit city.

They moved to “underground trenches where they had drinks and food and got training on different weapons”, he adds.

Similar stories had played out even earlier across other water-poor farming communities in Iraq’s north, according to Peter Schwartzstein, an environment correspondent and non-resident fellow at the Centre for Climate & Security who has tracked Isis’s rise to power. In Shirqat district, 120km north of Tikrit, extremists began skirting agricultural markets and zeroing in on the most impoverished-looking farmers as early as 2009, after two particularly harsh drought years. The area has traditionally relied on rain to irrigate its crops, but with rainfall fast becoming sporadic and erratic, the farmers were suffering.

In Kirkuk a few years later, jihadis were appearing at cattle markets, eyeing up farmers who were forced to sell their livestock because they had no means of keeping their cows alive with no water.

The farmers who signed up had power and status. Those who refused, like Nawaf, were forced to hand over 10 per cent of their crops by the jihadis who terrorised the community and enforced punishing taxes. If people did not obey they had their electricity and water supplies cut or in some cases were sent to trial. It prompted a second wave of farmers swapping their rakes for rifles.

In total 5,000 farmers from the Saladin and Kirkuk areas signed up, according to Naseer Tareq, a rights activist from Tikrit who works on water shortage issues for Save The Tigris campaign.

“Most of the farmers are not educated, they do not learn about religion, they know little about national politics. At the time they didn’t know the difference between government forces or any other armed group, they just needed the money,” he says.

It seems hard to believe that there was a correlation between one of the world’s most terrifying jihadi groups and water shortages, but experts argue Iraq’s water woes helped to fuel Isis’s recruitment drive in the north of the country.

Those same experts now warn that if the country’s water problems remain unchecked and people’s livelihoods continue to be destroyed, it would leave fertile ground for possible renewed radicalisation or at the very least further unrest.

While Isis was not formed from environmental issues alone, there is a very clear link

“While Isis was not formed from environmental issues alone, there is a very clear link,” says Schwartzstein.

He says if you pencil out the water-poor areas like Saladin and Kirkuk they almost exactly correlate with areas of heavy recruitment.

According to Schwartzstein, the issue first manifested in 2010 after nearly 15 years of terrible droughts.

That was also the year that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was appointed leader of what was then known as Islamic State in Iraq. Baghdadi replenished the group’s leadership by targeting former Iraqi military and intelligence officers who served under Saddam Hussein.

The foot soldiers were stocked by the most impoverished. Vulnerable struggling farmers were seen as “more susceptible to alternate employment”, Schwartzstein says.

“A terrible economy is a driver for desperate young people who haven’t got alternative means for employment. Agriculture is pretty much the only job in town. When that is rendered more or less unviable by water scarcity, people are unsurprisingly more easily swept up by recruiters.”

There are now concerns for the future. Tareq from Save The Tigris says that, despite what northern Iraq has gone through, there has been little movement to help the farmers who are now reeling from the destruction caused by several years of fighting as well as new and worsening droughts.

“We are worried what will happen if the situation here remains the same. The government must provide jobs, they must provide assistance to the people. We as civil activists are doing our best. But we need help. Not just local efforts, we need international support.”

Isis caused untold damage during its three-year reign and then used scorched-earth tactics during their retreat. The battles to regain the territories also contributed to the injury to water infrastructure, rivers and groundwater reserves.

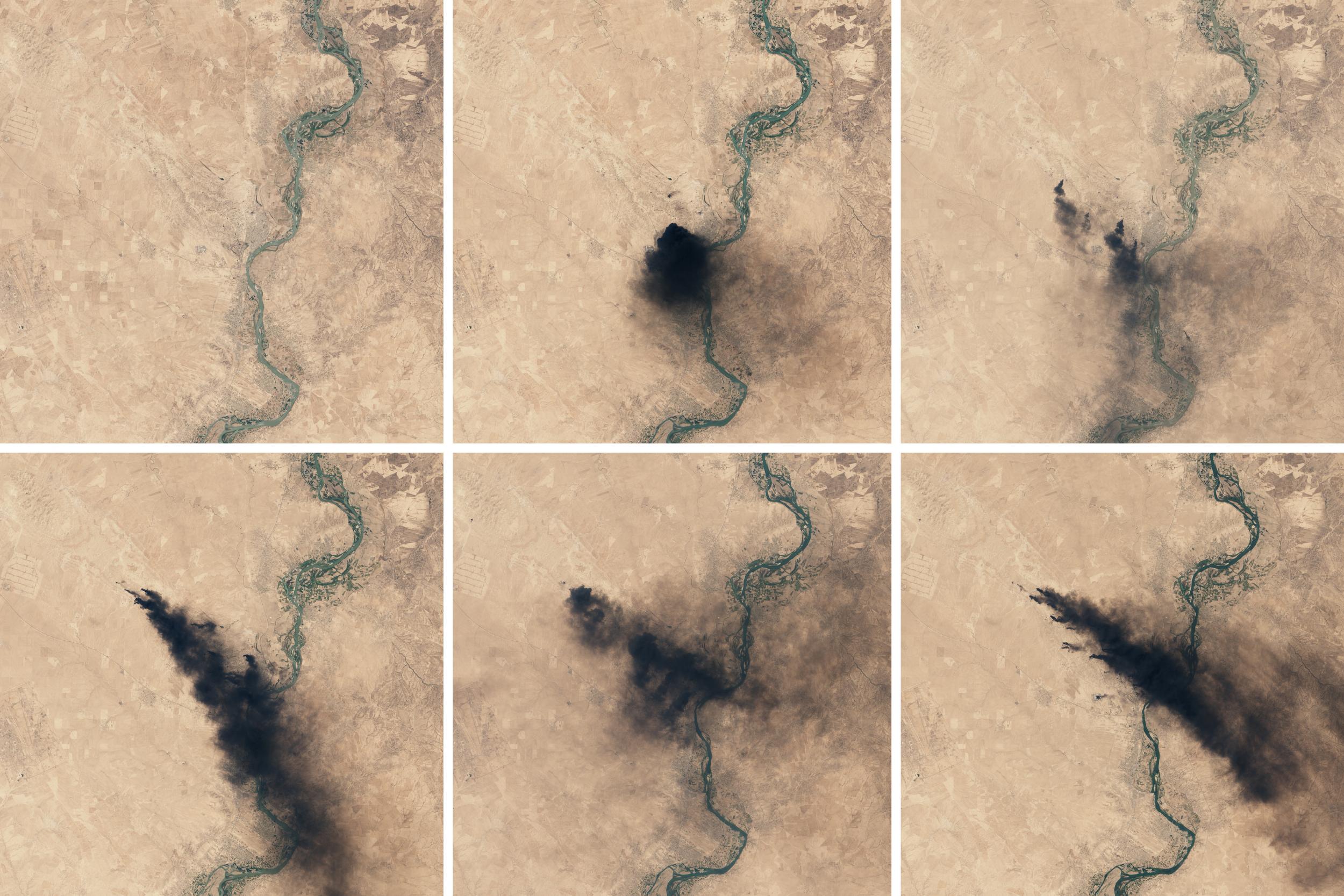

Wim Zwijnenburg, a lead researcher at the Dutch not-for profit PAX, which has been trying to track the environmental impact on the population, says Isis has used the environment as “a weapon”.

He says crude oil and wastewater spills, as well as the burning of wells and sulphur plants, saw oil, toxic gases and soot spread over vast areas. It has coated soil and livestock, and has polluted ground and river water.

No one truly knows the extent of the long-term damage on agriculture and livelihoods and what that could mean for the security of Iraq. This is largely because it has not been a priority for the authorities or international organisations that are struggling with mass displacement and destroyed cities.

“The problem is that the environment is not seen as part of emergency response,” Zwijnenburg says. “The focus of humanitarian organisations is understandably saving lives. It is all about medical help, food shelter: safety that is their focus. The environmental impact and long-term health risks come after this, if at all.”

In Qayyarah alone Isis blew up 18 of the 29 oil wells. They also set fire to Baji oil refineries, Iraq’s largest, and oil wells in the Hamrin mountains. Black toxic clouds hung over the area for nearly nine months. Experts are still trying to quantify the soot contamination of the soil and the water.

The rise of artisanal oil refineries – PAX has identified nearly 2,000 of them in Iraq – during Isis’s three-year hold on the region added to pollution and additional health risks to communities.

Over the years the jihadis also blew up pipelines, which caused severe pollution to the Tigris river. The only way the embattled Iraqi authorities could deal with the spills was burning the oil, causing more damage.

The Tigris was also hit during the battle for Mosul when jihadi fighters dumped chemicals and bodies in the river to scupper downstream operations. At the time Oxfam had to shut down its filtration plants because of the extreme levels of pollution. There are still untold levels of contamination.

Isis also “weaponised water” by taking over critical dams, so they could cut off water supplies or release floods to control government-held areas, Zwijnenburg says. While there were extenuating climate issues, the 2014-15 drought in central and southern Iraq was arguably a result of Isis blocking water flows.

While that had a crippling temporary impact, the Ministry of Water Resources estimates that Isis caused $600m (£457m) worth of damage to hydraulic infrastructure which, according to PAX, is still in need of urgent rehabilitation and maintenance.

But the water ministry lacks the funds to fix this: its budget has plunged from $1.7bn to just $50m, due to plummeting oil revenues and the war efforts. Most of those funds are used to pay staff salaries.

The focus of humanitarian [groups] is understandably saving lives. The environmental impact comes after this, if at all.

In the interim, farmers say the pollution has only exacerbated the escalating water shortages sparked by upstream dams on the Tigris in Turkey as well as climate change, which saw a dry winter last year and yearly rising temperatures.

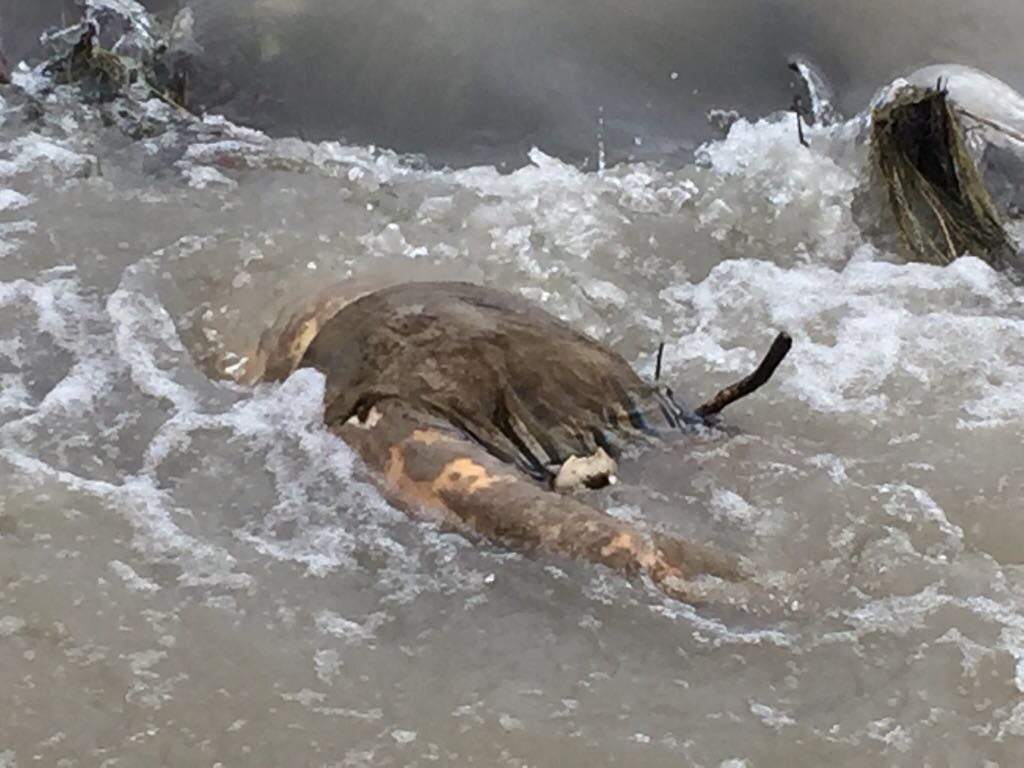

Nawaf, the farmer, says amid plunging water levels they are relying on saline water, which is wreaking havoc and killing livestock.

“The village where I live lost over 100 feddans [acres] of farmland due to saline water. I personally used to own 50 feddans and lost about 30 of them. Of course, we have to give animals fresh water. But due to scarcity; we cannot give them enough,” he says.

“If you walk around the village you can see bodies of dead animals. Sometimes, we have to resort to killing them and use them as food right before they die. The only way right now is to buy $50,000 desalination equipment – a hefty price for most of us here.”

This is contributing to mounting resentment against the authorities, according to Hamid Shehab, another farmer.

He says the current lack of water and electricity is so extreme that life is “almost as bad when Isis was here”.

“The current situation is terrible. There is absolutely no support. We cultivate spelt and barley. I used to be able to plant 3,000kg of spelt but now this is down to barely 1,000kg”, he says.

It’s almost as bad as when Isis was here

“It’s almost as bad as when Isis was here. The government owes us so much money,” he adds.

Abdullah, another farmer, says that other infrastructure issues such as lack of electricity (Isis has attacked the power lines) were adding to the problems. Farmers rely on electrical pumps to access underground water reserves for irrigation.

“I used to have 750,000 sq m but now I can barely cultivate 100,000 sq m due to water and electricity shortages. We don’t have money to buy generators and we cannot farm our lands,” he adds.

Zwijnenburg warns of the devastating consequences if the environmental and water crises are not properly addressed.

“This is a regional issue that also impacts other countries,” he says. “It isn’t sensationalist at all to say that land in Iraq is becoming uninhabitable, driven by spiking heat records, depletion of water resources, failed management and conflict pollution. The lack of agriculture also means loss of jobs, and relying more on imports, contributing to wider concerns over environmental security.

“There is an environmental legacy of failure in Iraq. It is coming all together as a cocktail of concerns that has already started brewing and is already exploding in the south.”

For the farmers this is translating into anger against the authorities.

“We have been through enough,” Abdullah concludes. “For farmers, giving up their crops is giving up on their dignity.”

Additional reporting by Mohamed Ezz

Read the first three parts of the Water Wars series, Boiling Basra, Iraq’s disappearing Eden and How a water crisis in Jordan could threaten Middle East peace

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments