Desperate Yazidis fear the worst as they face winter without shelter

The ancient Yazidi people were forced to flee from Isis fighters and seek refuge in the Kurdish territories. Many have lost everything

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Aziz, a young Yazidi man holds up his phone and shows a video of what looks and sounds like a fireworks display on a dark night.

He explains that “these are the gun flashes from the weapons of Da’esh [Isis] fighters when they entered our village of Gire Ezer on the night of 3 August and killed between 200 and 300 people.”

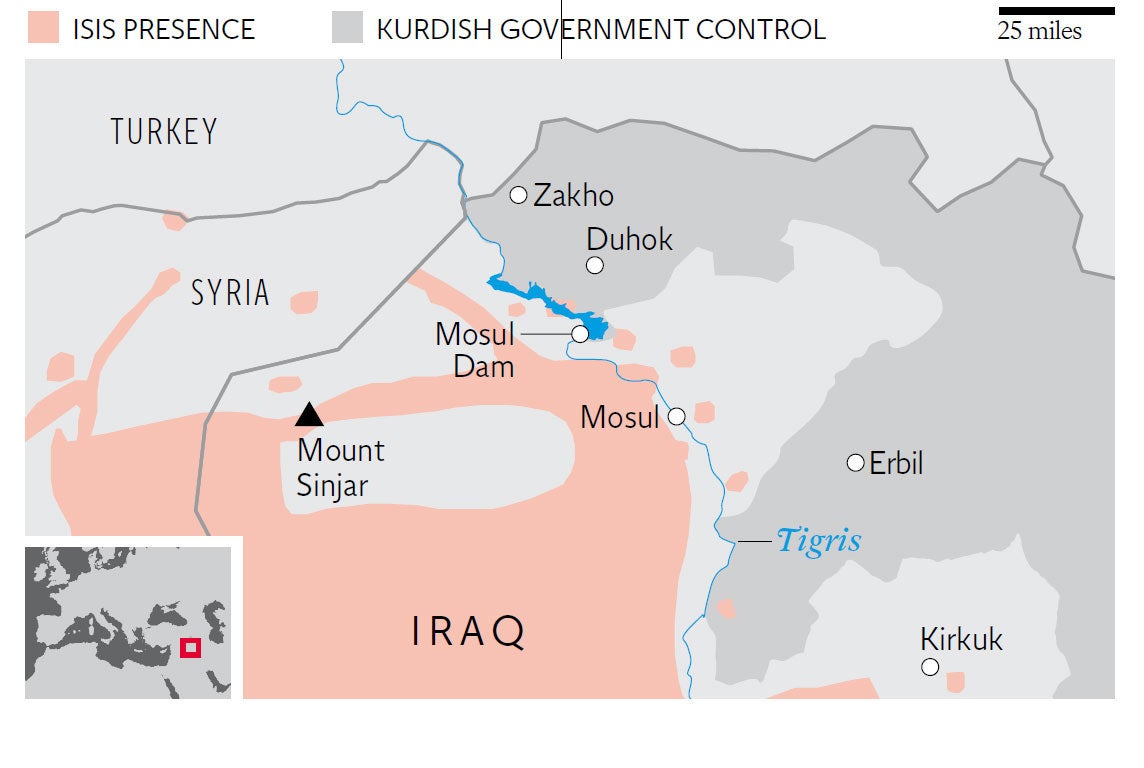

The surviving Yazidis from the village, mostly poor farmers and labourers, fled in panic from their homes in the Sinjar mountains to safety in the territory of the Kurdistan Regional Government where they joined 300,000 or more other Yazidis fleeing massacre, rape and enslavement by Isis. They had first been housed in a school in Zakho and, on day we met them, were being moved to a camp called Bercive in a valley filling up with large tents. It is getting cold in northern Kurdistan and Aziz’s father, Mahmoud Matto Abbas, complained that there so far there was no heat, water or electricity.

At the time of their first flight in August, the Yazidis, a Kurdish-speaking community with their own ancient religion, achieved notoriety for the first time in their history as thousands of them were trapped on Mount Sinjar, their holy mountain. Television showed biblical scenes of terrified Yazidis trying to escape slaughter. President Barack Obama sent US Special Forces to report on their condition and started bombing Isis’s motorised columns. But in September and October the television cameras departed and international attention switched to the siege of the Kurdish town of Kobani.

The Yazidis of Mount Sinjar were largely forgotten though 6,000 or more of them, many of them fighters and their families, remain there, surrounded by Isis and with one road intermittently open into Syria. They receive supplies from two Iraqi army helicopters and a C-130 transport as they defend their temples from being destroyed by Isis, which demonises the Yazidis as infidels. People warn that winter weather may cut the road and Isis may then renew its assault.

Most of the 576,000 displaced people in Duhok province are Yazidis. Their religion is a blend of traditions including veneration for fire from the Zoroastrians, baptism from the Christians and circumcision from Islam. But at the centre of it is the Peacock Angel, leading to their persecution as devil worshippers.

Mahmud Matto Abbas says that what these people had in common long before the arrival of Isis, was poverty. He says, “everything in our region was miserable: we didn’t even have enough petrol or cement to build houses. Until we got here, nobody helped us. We asked the Peshmerga [Kurdish soldiers] and the Iraqi government for weapons to defend ourselves against Isis but they ignored us.”

He said that the only people who had helped them escape were the PKK Turkish Kurds guerrillas, many of whom had been killed by Isis while doing so. He wondered why the US and Turkey called the PKK “terrorists”, when he and the other Yazidis had nothing but praise for them.

Since arriving in the area controlled by Kurdish Regional Government, the Yazidis have been housed and fed by the combined efforts of the Kurdish government, UN High Commission for Refugees and the World Food Programme. But 1.8 million people have been displaced in Iraq since Isis seized Mosul on 10 June of whom over one million are being fed by WFP at a cost of $29m (£18.5m) a month. The UN agencies complain that even if their efforts have been successful so far, they are rapidly running out of money.

The Yazidis had little money to begin with and have mostly spent it. Chloe Cornish, of the WFP, says that she had noticed that many young Yazidi girls had gold earrings when they arrived “but less and less so because their families have had no income for three months and have to sell their gold.”

The precise day on which the Yazidis fled their land makes a big difference on the accommodation and level of assistance they receive in Kurdistan. Those I spoke to who left on 3 August were housed in schools. But those who left later in August found the schools filled up and took refuge in half-constructed buildings. Near the zoo in Dohuk city, some 250 Yazidis who had not left until 6 August, ended up in a four-storey structure with just concrete supports and no walls. “We cannot sleep, it is so cold,” said one man.

There is a numbed and despairing resignation about many of the Yazidis who have lost everything. Haji Ayyo Eabo said: “I have spent my life saving money to build a house, but I had lived in it for only a month when I had to run for my life.” He pointed to an elderly man with a white walrus moustache, saying “he used to be one of the wealthiest men in our village with 60 or 70 sheep and goats.”

Many speak of relatives who did not make it to safety and express anger at the speed with which the Peshmerga, who were supposed to be defending Sinjar fled, often without firing a shot. Yusuf Amar from Tel Qasar village said “the commanders of the Peshmerga fled and their men told us ‘get out, our commanders have disappeared and we are going to go’.”

There is a feature of the flight of the Yazidis that is likely to produce further violence in future. The Yazidis complain that the Sunni Arabs who lived near them sided with Isis and aided in the massacres, sometimes even beginning the killings before Isis death squads arrived. It is difficult to know how true this is, but it will make it next to impossible for Yazidis and Sunni Arabs to live together when the Yazidis return to their villages as they fully expect to do.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments