David Nott interview: War surgeon reveals how healthcare workers are being 'systematically' targeted in Syria

'Healthcare is seen as a weapon – you take out a doctor, you take out 10,000 people they can’t care for'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

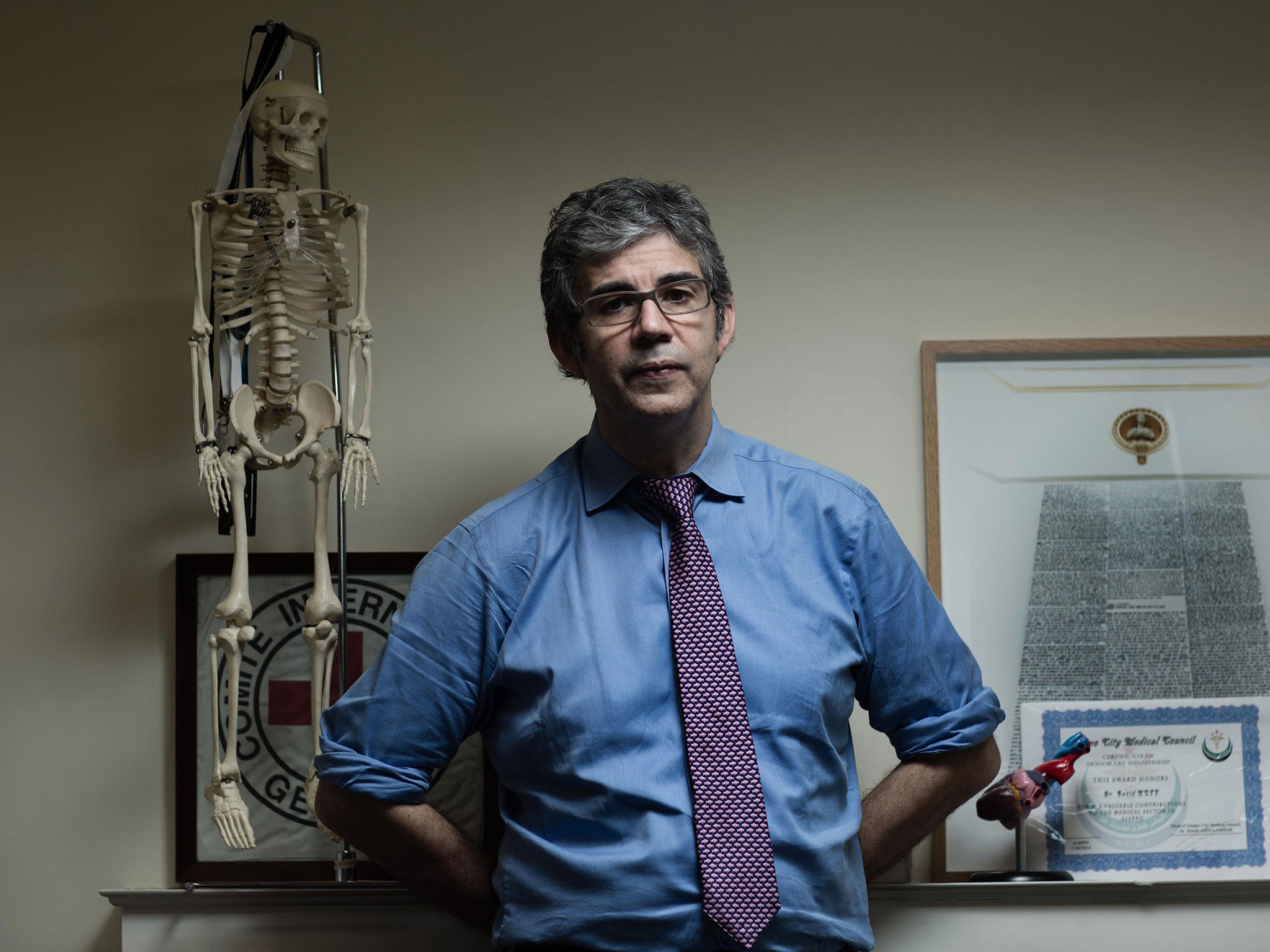

Your support makes all the difference.David Nott, probably the world’s most experienced war surgeon, has grown used to loss.

As he looks back over photos of his last visit to Aleppo, Syria, he pauses for a moment over a picture of two young doctors, smiling at the camera in their blue scrubs.

“He was an anaesthetist I knew. He was killed two weeks ago last year. An air-to-ground missile,” Dr Nott says, sad but matter-of-fact, pointing to one of the pair. “And he was killed not long before,” he says, indicating the other. “Doctors are targeted.”

In the grim logic that has taken hold among the forces of President Bashar al-Assad and his allies, “healthcare is seen as a weapon”, he says. “You take out one doctor, you take out 10,000 people he or she can no longer care for.”

Dr Nott is known in the press as the Indiana Jones of surgery, a title he has never liked, but which attaches itself somewhat inevitably to a man who has saved lives in most of the world’s major conflicts since Bosnia in 1993.

Still holding down a day job performing three different kinds of surgery at three different London hospitals, he is one of the country’s leading surgeons – and last week it was announced he was this year’s recipient of the Robert Burns Humanitarian Award.

Every year he takes up to three months’ leave to work in conflict or disaster zones. Sometimes in ramshackle clinics, sometimes with rudimentary instruments, he has operated in Sierra Leone, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. He was with the Defence Medical Services in Basra, Iraq, in 2007 and has served at Afghanistan’s Camp Bastion.

He has made headlines saving the lives of a baby retrieved from the rubble of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and of a Congolese man whose infected shoulder he amputated in 2008, with instruction from a British colleague over text message – it being the first time he’d ever carried out the procedure.

But nothing has compared to his experiences in Syria where, he says, the work and lives of healthcare workers like him are under threat as never before.

“Nearly nobody is reporting this, the direct attacks on healthcare and healthcare workers,” he told The Independent last month, citing figures from the NGO Physicians for Human Rights, which recorded 23 attacks on medical facilities in Syria in October and November last year – all but one by Syrian government or Russian forces.

The United Nations Office for Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs also reported that 20 health facilities were struck or damaged by aerial bombs dropped by the Assad regime or its allies in October and November, and that many aid organisations have had to scale back or suspend their operations as a result of increasing attacks. In December, Amnesty International said Russian air strikes had killed hundreds of civilians – and hit medical facilities.

Aid workers believe the increasing frequency of such attacks suggest a strategy. Nott has long been convinced that both Syrian – and now Russian – forces are intentionally hitting hospitals: a view that is shared by the Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond, who accused the Russians of deliberately targeting civilians, hospitals and ambulances after speaking to Syrian civil defence workers in Southern Turkey earlier this month.

“The nature of the bombing has changed so completely in the past few months. It has to be the Russians,” Dr Nott says. “Russian jets fly very high up. Syrian jets fly lower, firing rockets and missiles. The Russian planes tend to be 10,000ft up and you don’t see it, you just see the weapon hitting the hospital,” he says.

Hospital workers, supported by charities, have had to dig out new wards underground to escape the bombings. Now, Dr Nott says, because of the attacks, they are being driven to set up clinics in caves outside cities.

He has not been back to Syria himself since October last year, but has been in direct contact with colleagues in Aleppo and elsewhere in rebel-held northern Syria. Until a few weeks ago, he was regularly giving surgical advice and reviewing X-rays over WhatsApp messenger. But then the internet was cut off in Aleppo, and the messages stopped.

Dr Nott’s last memory of Syria is of a desperate journey from Aleppo to the border, in October 2014, after an aid visit in which barrel bombing by government forces was a constant threat.

“I was hearing every day the roads would close. If I didn’t leave then the road would be blocked – and you’d never see me again.

“There were Syrian jets circling around, there were people being shot at… I remember the route. You had to put your foot down until you got 10 miles out of Aleppo.”

Since then he has stayed in touch, and in April went to Gaziantep in Turkey to train Syrian colleagues in specialist trauma surgery.

He has grown increasingly frustrated that Western governments – fixated on the threat of Isis – have forgotten about the humanitarian disaster in rebel-held areas such as Aleppo.

“The healthcare workers I work with are not fighters, they don’t carry weapons, they’re just there to help,” he says.

“What is happening to them is totally against international humanitarian law – hospitals should be protected and they are being targeted. Targeted to ensure the destruction of the healthcare system.

“The British are fighting Isis – fair enough – but this is happening daily and has been forgotten about.”

In 2013, he called for humanitarian corridors to be set up to support populations trapped in conflict zones. Now, he says, a no-bombing zone is urgently needed over Aleppo and Idlib provinces, which the international community should set up, even if it meets with Russian opposition.

“It has to be achieved. Somebody has to stand up and say, ‘The humanitarian situation is so bad that this has to be achieved’. It is a systematic destruction of the healthcare system: a weapon of war which Syria and Russia are using at the moment. That has to stop.

“Make it an area refugees could come back to, protected by a peacekeeping force – I’m sure Assad and Russia would not start attacking any Americans that were there.”

The only reason Dr Nott did not go back to Syria himself in 2015 was an unanticipated but very welcome event – the birth of his first child.

Dr Nott was married in January to Elly, who used to work for the Institute of Strategic Studies in Bahrain and now leads the newly formed David Nott Foundation, which raises funding for the training of conflict surgeons. Their daughter Molly was born in July.

However, Dr Nott does not think fatherhood spells an end to his humanitarian work – though he may cut it down to six weeks in the year.

“Elly knew who she was taking on. She knew what this is all about and she loved that person,” he says. “The world is very dangerous, no matter where you go to do this. You can reduce the risk by thinking about the places you go to. I probably wouldn’t go to Syria at this moment in time or to Afghanistan. But the rest of the world is out there to be helped.

“I can’t withdraw from it. I’m probably the most experienced war surgeon in the world. I can’t stop doing it now I have a family. I wanted to have one, I wanted to have things other people had. But it would be a shame to withdraw now because there’s so much still to offer, and a new generation to teach.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments