As Syria's civil war rages across the boarder, Lebanon's Baalbek festival defies the bombs among the temples of the gods

Despite being seven miles from the war, the venerable music gala has been attracting thousands to its performances amid the Roman ruins

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

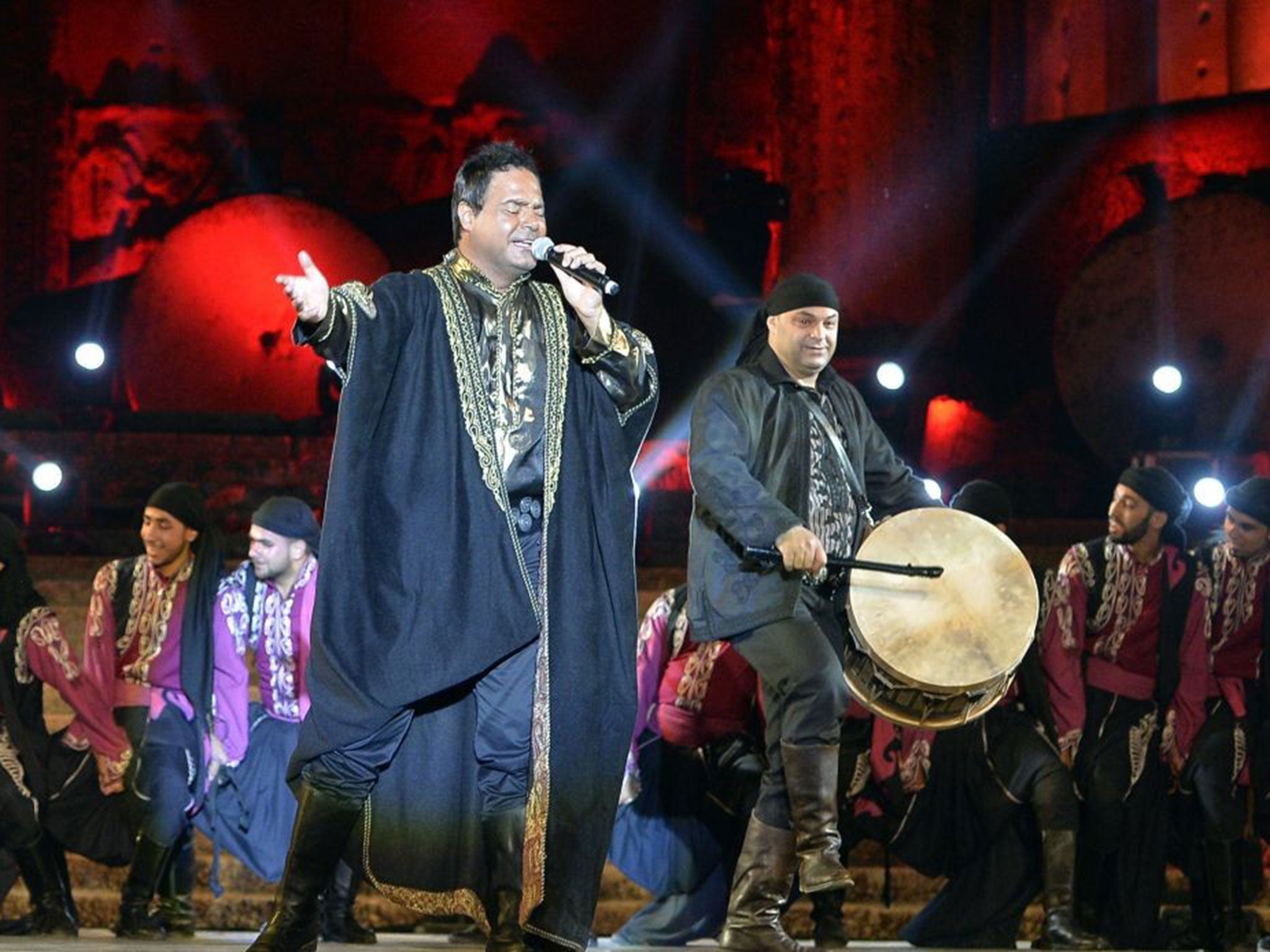

Your support makes all the difference.As a group of traditionally clad dancers emerged from the lit-up temple of Bacchus in Baalbek, a roar of approval came from the crowd. The audience danced, clapped and sang along as Assi el Helani, Lebanon's version of Tom Jones, took to the stage and sang an ode to Baalbek, his home town.

The message the 3,000 filled seats sent was clear: Baalbek festival is here to stay. "It was a great challenge," said Nayla de Freige, president of the festival. She hoped the two sold-out opening nights would reassure people that Baalbek was safe to visit, despite being located scarcely seven miles from the Syrian border. The area is a stronghold of Hezbollah, which is fighting alongside President Bashar al-Assad in Syria.

Last year, the festival had to be moved to a silk factory closer to the capital. The Roman ruins where the festival had been held since 1956 were deemed too unsafe. "It was totally for security reasons. Two rockets fell down not very far from the acropolis," explained Ms de Freige.

Now the festival is back among the temples of the gods, one of the best-preserved and largest Roman temple complexes in the world, and a Unesco World Heritage site. Children pose for pictures against the majestic backdrop of the six remaining columns of Jupiter's temple, built in 64BC.

But it has been a struggle to get here. When the committee presented its programme from the acropolis in May, it was certain that a triumphant return lay ahead. "We were in euphoria. We thought that everything was going to be great, and that we were going to have a fantastic tourism summer," said Ms de Freige. But then a wave of suicide bombings and arrests hit Lebanon in June, changing everything. Meetings with all the security services and Hezbollah followed.

The opening-night performance, scheduled to start "at eight prompt", was delayed by an hour. There were television transmission issues, and the ministers of culture and tourism were stuck in traffic.

The road between the capital and Baalbek was clogged up by seven army checkpoints, the last four of which were on the final 25 miles. At the entrance to the temple complex, heavily armed soldiers and police stood guard while men and women were separated and searched for weapons. These intense security measures were carried out at the request of the organisers, who co-ordinated with the army for months in an effort to ensure safety for festival-goers in one of the country's most volatile areas.

Still, that wasn't enough for some performers. Canadian dance troupe Les 7 Doigts de la Main cancelled three weeks before the festival, because of security concerns among the young performer's parents.

Last week, Romanian opera diva Angela Gheorghiu asked for her concert to be relocated to the casino, which is located on the coast, a traditionally safer part of the country. The French actor Gérard Depardieu is the only newcomer, in a double act with the French actress Fanny Ardant, a veteran of Baalbek. Tunisian oud player Dhafer Youssef, too, had previously performed in Lebanon. The organisers consciously approached people who knew "the sensitivities of the region", as Ms de Freige delicately put it.

It has been quite a change of pace for a festival that used to host the greatest stars in the world. During the 1950s, there was a focus on theatre, with lots of Shakespeare performances, including by the Old Vic Theatre Company. The Royal Ballet was recurrent a guest in the 1960s, and the New York Philharmonic came as well. The 1970s brought jazz to Baalbek; Miles Davis performed and Ella Fitzgerald came two years in a row.

The stage remained empty for more than two decades following the start of the country's civil war in 1975 but, when it restarted in 1997, it still managed to pull in the big names. Nina Simone, Sting and Phil Collins all performed in the shadow of Jupiter's temple, alongside operas, musicals and dance troupes.

Tickets would sell out weeks in advance; now, every single concert has tickets available and 300 people bought their opening-night tickets at the door. Last-minute ticket sales are up; people want to assess the risk on the day of the concert.

And the audience is mostly local; there are fewer people from Beirut than usual and foreign visitors are greeted with surprise and delight. A successful run of the festival could help to bring back other tourists to Baalbek, whose car parks are mostly vacant as embassies advise their citizens to stay away.

Organisers see the festival as a barometer for the state of Lebanon. "If Baalbek is OK, the rest of the country is OK," said Ms de Freige, who came on board when the festival restarted in 1997.

She has seen the festival landscape change; before the war, Baalbek was the only festival in the country and the region. Now there is a lot of competition – although, as she said, Baalbek's stunning location and reputation set it apart from the rest: music fans could hear Katie Melua sing in the courtyard of the Ottoman Beiteddine Palace or Massive Attack play their greatest hits by the sea at the Phoenician-era town of Byblos. Welsh Baritone Bryn Terfel opened the Zouk Mikael festival on Thursday to a half-empty theatre. "All the festivals are having a tough time this year," said Ms de Freige.

Older visitors relish the memories of classical music concerts and performances by local legends. "When you hear Fairuz in this location, or Beethoven, you fly," said Fahmi Shraif, a local tour guide. He wasn't much impressed with the populist crooning of El Helani, calling his Arabic lyrics third rate. "They are cutting down the temple," he scoffed, as one of El Helani's protégées from the Lebanese version of the television programme The Voice, where he is a judge, started a cover of Gloria Gaynor's "I Will Survive".

Though perhaps out of sync with the festival's rich history, it was a message that symbolised the Baalbek festival's spirit. Organisers have vowed to continue organising the festival here, where it belongs. "This is our cultural resistance," said Ms de Freige. "We need to show that Baalbek is a part of Lebanon and it wants to have joy, wants to live."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments