As survivors dwindle, what will this mean for memories of the Holocaust?

So long as there remain those who question the existence of the state of Israel, the descendants of Europe’s Jews will strive to keep the memory of Nazi war crimes alive

When the First World War centenaries are commemorated during the next four years, there will be no one to provide living testimony; these will be anniversaries that have passed from memory into history.

The same is increasingly true of the Second World War, as is graphically, and touchingly, apparent from the dwindling number of veterans marching past the Cenotaph each Remembrance Day. The passage of time is as relentless as it is natural.

But because the settlements that followed those wars have now been superseded – in the case of the First World War by the tensions that precipitated the Second, and in the case of the Second World War by the reunification of Europe – it can be argued that this does not matter. There will always be room for reassessments and reinterpretations on the basis of the documents and memoirs of the time. There will always be parallels, if sometimes misleading ones, to be drawn with the present. And, consciously or not, many of the next generation will have absorbed reminiscences from their parents.

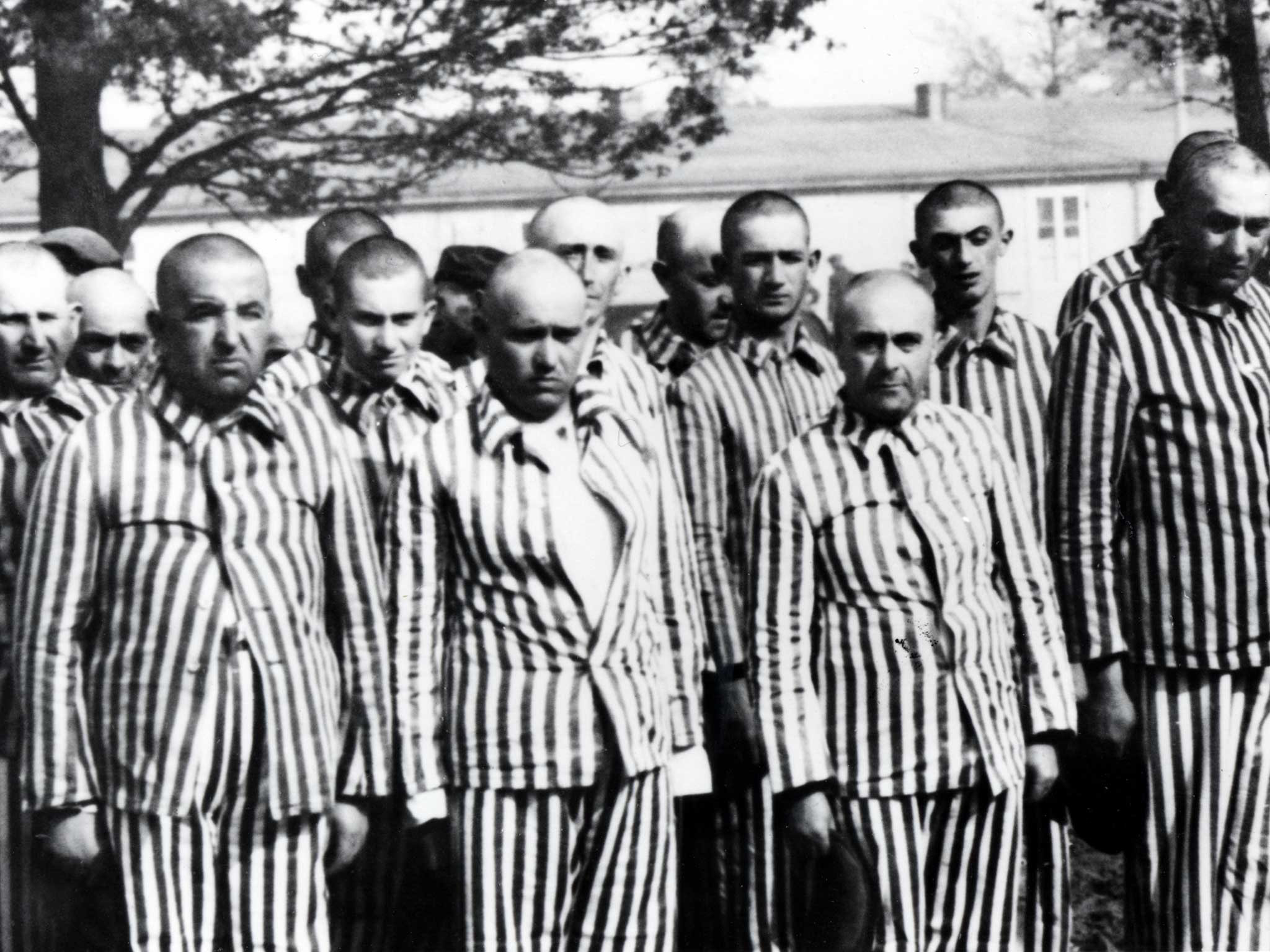

There is, though, an exception – an exception that is more keenly felt as each year passes. The descendants of Europe’s Jews, especially those now living in Israel, feel that the post-war settlement has not been completely accepted, let alone superseded; nor do they feel that the lessons of that experience have been fully learned. So long as there remain those who question the existence of the state of Israel; so long as there remain those who challenge the truth of the Nazis’ systematic attempt to destroy Europe’s Jews for no other reason than their Jewishness, they will strive to keep the memory alive – as memory, not only as history.

Nor are they wrong to do so. As courts down the ages have recognised, there is no substitute for eye-witnesses – living, breathing people who can tell it in their own words and answer questions from the curious, the sceptical and the appalled. Yet those witnesses, like the Second World War veterans at the Cenotaph, are fewer and fewer. Today’s Holocaust survivors experienced the ghettoes, the death marches and the camps as children.

At a seminar organised by the International School for Holocaust Studies at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem last month, our penultimate meeting was with one of those children who remembers. Now in her late seventies, Rena Quint is a handsome woman, at once strong and fragile. She was born into a comfortable middle-class family in the town of Piotrkow, near Lodz in Poland. Before she reached the age of 10, she had experienced the descent from a normal family home to the ghetto, thence to the concentration camp at Treblinka and finally to the death camp at Bergen-Belsen.

In her case, that “finally” was not to be the last chapter. Rescued by British forces when Belsen was liberated, she was adopted by an American-Jewish family – as the last-minute replacement for a little Jewish girl who had died. Mostly, though, she was brought up by a different family after her adoptive mother suddenly died. Quint moved to Israel later in life and, like so many, after all the wandering, felt that to be her true home.

Of her early life, she offers mere sensory fragments: the remembered smell of fresh bread as she was taken by sledge on her mother’s daily trip to the baker’s; the unspeakable conditions on the cattle-cars to Treblinka – “the stench is something that will never leave me”; the dogs unleashed at will by the German camp guards to intimidate. “The barking haunts you for ever,” she says.

Small, telling episodes stand for the whole personal, and collective, catastrophe. Losses plague her still: from the father dispatched to Buchenwald, pledging to see her again in Poland, to the camp guard who prised the last photos of her parents from her clenched fist and tore them to pieces in front of her eyes. “I tried so hard to picture my mother or father,” she says, but there is no visual record.

Like so many, Quint was the only survivor from her whole family; she knows of only two distant cousins. In the transports and the camps, she was shielded by a succession of new “mothers”, and each might give her a new name. One of these women, she says, “stole a black coat, which saved the two of us. I don’t know what happened to her, or the coat, but she is one of those who saved my life.”

So inured was she to death, that when her first American adoptive mother died, she was amazed at “one person being buried, one little hole in the ground, and everyone is crying...” One can only surmise the consternation, disapproval even, of her adoptive relatives, who would have had no conception of her previous life.

Such individual testimony is as effective in conveying the experience of Europe’s pre-war Jewish communities as it is impressive. As I write this several weeks later, I can see Rena Quint clearly before me; the bare classroom where she was speaking fades into sepia images of a typical ghetto and then into the grainy, black-and-white footage that records the liberation of Belsen. And I can reproduce from memory much of what she said – accurately, when I later check against my notes.

Her memories are all the more poignant for their lack of personal rancour or propagandistic drive. Of the attitude of her non-Jewish Polish compatriots, she says: “They didn’t ask questions; nobody knew and nobody cared.” Of Germans in general, she says: “I won’t ever forgive them and won’t forget, but you can’t live for ever with hate, and they did help us build a state.”

Underlying Quint’s practised, but occasionally halting, narrative can be sensed, at times, a hint of defensiveness. She was, after all, just a young child during the war. Had her memories perhaps been overlain with what she might subsequently have been told? She accepts the question, but says that, visiting Poland for the first time, in 1989, she found “documents, the house, the factory all as I had vaguely recalled and had sometimes doubted. Everything I had said was true.”

Like other survivors who speak publicly about their experiences, Quint feels an obligation to do so to ensure that this history never repeats itself and, as she also puts it, to “make sure Israel is safe and free”. She seems remarkably resilient, as she would have to be to recount this past for an audience. Growing up, yes, there had been nightmares, but “I treated them as just that, nightmares”. As for delving more deeply into her experiences, she says, she had never sought analysis or hypnosis: “I’m not sure I want to open up that Pandora’s box.”

As the last living keepers of the memory, articulate survivors such as Quint are treasured by their fellow Jews, as well they might be. No matter how familiar, and horrific, the collective experience may be – and I have visited perhaps half a dozen concentration camp memorials over the years and heard the harrowing reminiscences of more than one survivor – there is no substitute for just one individual’s testimony, spoken face to face. As the number of those who remember declines, so – inexorably – the link between that past and this present is loosened.

A logical consequence of this fading of memory into history, it might seem – at least to outsiders, such as myself – is that the founding mythology of the Jewish state will also be eroded. After all, the experience of the Holocaust seems to support so much of Israel’s contemporary identity. Will the well of shared suffering not start to run dry without the likes of Rena Quint and her memories to replenish it?

This is not a view generally accepted by researchers at the memorial complex at Yad Vashem. They challenge the idea that living memory is, or ever was, as crucial a philosophical buttress to the state of Israel as many believe. As David Silberklang, one of Yad Vashem’s senior historians, argues, the Allies’ post-war sense of guilt was only a secondary consideration, if it was a consideration at all, in the recognition of Israeli statehood. The state created in 1947 was rooted in much, much older historical considerations, and a large measure of contemporary realism: if there was to be a Jewish homeland, this is where it was going to be, and in practical terms, with most Western countries closing their borders, there was nowhere else for war-torn Europe’s dispossessed Jews to go.

In fact, says Dr Silberklang, the Holocaust was not part of the discussion in the early years of Israel, and for good reasons. One was that European Jews did not then constitute the majority of Israel’s population. Many founding citizens were Sephardi Jews from North Africa. This changed only with the arrival of Soviet Jews in the 1970s, who brought with them new memories of persecution.

An equally compelling reason was that the survivors of European Jewry wanted nothing more than to live their miraculously spared lives; they tried less to remember than forget. This only changed – as Rena Quint also noted – with the trial of Adolf Eichmann for war crimes in 1961. The complex at Yad Vashem, established by an act of the Israel parliament, the Knesset, in 1953, was almost 20 years in development and deliberately kept at arm’s length from the state. It is funded by a grant administered by parliament and governed by an independent board.

Nor, it transpires, are all Israelis happy with the way the experience of the Holocaust has become so prominent a part of their state’s current identity. Something of a national debate erupted about this last year, after the Israeli air force staged a flight over the memorial at Auschwitz. Israel should not, objectors said, allow itself to be seen as nothing more than Yad Vashem and an air force. This only discouraged others from treating it as a fully paid-up modern state.

That familiarity with the Holocaust is regarded as an integral part of being both Jewish and Israeli is evident from the constant procession of school, college and conscript groups around Yad Vashem. Conscripts can expect to visit at least three times during their military service. Since the 1980s, learning about the Holocaust has also been part of the school curriculum. Again, this has drawn controversy, triggering a lively discussion about how to teach such horrors to children as young as six, and much emphasis on what is described as “age-appropriate” material.

The danger here, as is periodically pointed out, is that dwelling on the experience of the Holocaust risks reinforcing an image of Jews as eternal victims. This is something Yad Vashem’s recently redeveloped museum and its associated memorials are designed to contest. A leitmotif is the place of Jews, not as condemned people, but as a colourful part of life’s fabric in pre-war Europe; the focus is on survival, not exclusively on loss.

If there is room for debate about the place, and the use of the Holocaust in Israel today, and how far this might change as the survivors grow ever fewer, there is another area where there should be no need for debate at all. It is surely self-evident that the facts of what happened to Europe’s Jews, and not just to the Jews, but to anyone considered a threat to Aryan racial purity, should be disseminated as widely as possible. Nor is it just the facts of what happened that must be made known, but the whys and the hows, as the ultimate – perhaps only – way of preventing a repetition.

This is the greater purpose of Yad Vashem, both of the museum and the memorials, but especially of the voluminous, and ever-increasing, archive. The idea is to document every victim in as much detail as possible, so that each features as a person and not a number – the very opposite of how they were treated in the Nazis’ “industrialised murder machine”. Rigour and exactitude are key here – the most effective riposte to those who would quibble about numbers or query definitions of genocide.

As Soviet-era dissidents also knew, cold, hard, indisputable facts are the surest answer to sceptics of all persuasions. The archive, whose motto is “collecting the fragments”, receives on average 10 visitors a day offering documents or artefacts. Its director, Haim Gertner, tells touching stories of relatives handing over diaries and other documents for safe-keeping, and of others who change their minds at the last moment, unable to give up what may be their last tangible link with that past. In this case, the documents are simply scanned and returned. The archival technology is state-of-the-art and has made this work easier.

But there is also a recognition, forcefully articulated by Yad Vashem’s chairman, Avner Shalev, that, while there is an urgent need to collect stories and images for the next generation, “live witness means a great deal”, and when there is no one left to testify, “we’ll lose a lot”. There is a sense of time running out. For it is, paradoxically, as the living memory fades that its preservation becomes more necessary.

To offer just a tiny example: I was struck by the careless way in which one of the British Greenpeace campaigners released by Russia after Christmas described the prison as like a “concentration camp”; the interviewer prompted him to reword this as “suggesting the aesthetic of a concentration camp”, but the mark of ignorance was there.

Or this, from Henia Bryer, a Holocaust survivor in her eighties, living in South Africa, who featured in a gripping BBC documentary last year. “I had an operation once,” she said, “and the anaesthetist looks at the tattoo on my arm and he says: ‘What is this?’ And I said: ‘That’s from Auschwitz.’ And he said: ‘Auschwitz? What was that?’ And that was a young man, a qualified doctor.”

In the face of such short memories, or no memories at all, Yad Vashem has its work cut out for decades to come.

www.yadvashem.org

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks