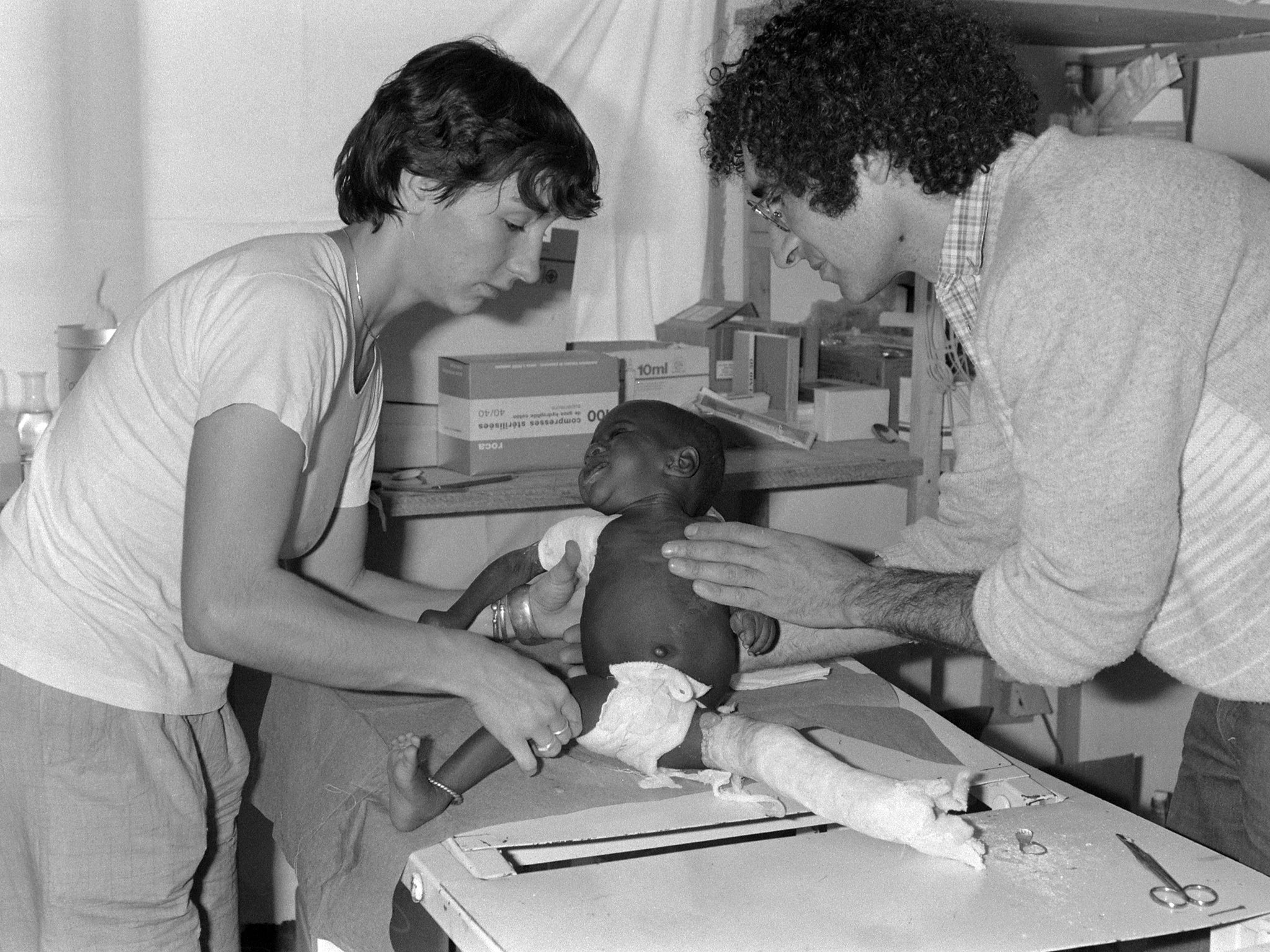

Medecins sans Frontieres: The Ebola crisis has them in the headlines, but their work goes far beyond West Africa

Jeremy Laurance pays tribute to the ethos of heroism that keeps it going

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was one of those breakfast radio moments that stops you in your tracks.

Whatever you were doing – brushing your teeth, making the toast – you had to pause to listen while Dr Geraldine O’Hara, a volunteer with Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) in Sierra Leone, described on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme the grief with which she watched the Ebola virus cut down a community health worker who was a member of her own team.

In her quiet voice with its soft Northern burr, she explained how the young woman – Satmata – had asked for bread and soup and taken herself out of the treatment tent to lie on a mat in the sunshine.

“When we find her she is struggling to breathe. We help re-position her to make her more comfortable. Her breathing slows. She dies. I say to Prince [a colleague], I am so sorry. I am genuinely upset for him. One of the nurses says to me, she is like a sister to us, she is one of us. Prince says this is a very difficult phone call to make [to the family]. I say to him, at least you can say you were with her when she died. She wasn’t alone.”

Dr O’Hara, who returned last week from her 25-day trip, was lauded for her audio-diary, broadcast over six days.

“I am keen people understand what is happening to the people there – but I don’t want a media career,” she says.

Seeing patients die is something all doctors have to face. But what is it like, I wonder, to watch a colleague dying? That is not something within most doctors’ experience and brings home, in the starkest way possible, the risks they themselves face. MSF, the largest international medical organisation in the world, sends its staff into the most dangerous trouble spots on the planet, and prides itself on being “first in, last out”. Today, it has more than 3,500 staff working in West Africa to contain the Ebola outbreak, including 263 international volunteers (13 from the UK with 20 on the way). Of these, 24 have been infected by the deadly virus (most from contact with their own communities but including three international staff) and 14 have died – so far. It is the biggest death toll from Ebola in the organisation’s history.

“It is incredibly upsetting when a colleague dies. The nursing team had previously lost other members. How do you carry on? You have to. You have still got 70 patients there who need looking after. The local staff keep coming to work despite everything. I can go home after three-and-a-half weeks but they are still working there,” Dr O’Hara says.

Aged 36, she is an infectious diseases specialist at University College Hospital, London. She has worked for MSF before – eight years ago in Somalia, from which she was evacuated twice because of security concerns – and plans to again. She hopes to return to Sierra Leone in the New Year and expects to continue working for MSF in short stints throughout her career.

The director of the UK’s largest medical charity, Jeremy Farrar of the Wellcome Trust, last week described MSF’s response to the Ebola outbreak as “simply heroic”. It is an accolade that Dr O’Hara rejects. What draws her and the 3,000 other international volunteers dispatched annually by the organisation to work alongside 25,000 locally hired staff in the 60 countries around the world where it operates, is the opportunity to make a difference. “I go and do the work because I love it. It is very interesting professionally – I have seen more Ebola than most of my colleagues – and from a personal point of view it is very rewarding. It is an opportunity to help people who would otherwise not get care,” she says.

MSF goes where other charities fear to tread. When the Ebola outbreak escalated in West Africa earlier this year, many aid organisations already operating in the region abandoned their projects and left in terror. MSF was the first to respond a year ago and for many months was the only organisation providing help on the ground – a fact for which it lambasted the international community.

That is its other distinctive characteristic. Unlike rival charities – the International Red Cross, for example – MSF has an explicit policy of “bearing witness”: speaking out to galvanise action when circumstances demand. It was its founding principle, when set up by a group of French doctors and journalists in 1971 during the Biafran war. They were outraged by the aid community’s silence at Nigeria’s blockade and starvation of separatist Biafra, in which one million civilians died.

They included the radical young physician Bernard Kouchner, who had played a leading role in the May 1968 student protests and later became France’s health minister (three times) and then foreign minister under President Sarkozy. Kouchner’s doctrine was that morality cannot stop at borders and that when confronted by extreme wickedness, politics and not just medicine should be “sans frontières”.

But Kouchner’s uncompromising stand caused difficulties for the organisation in working with governments and other aid groups. In 1990 he split from MSF to found Médecins du Monde, which has developed in parallel but is smaller and less well-known than its older sibling today.

Vickie Hawkins, current director of MSF UK, says: “Our roots are in radicalism. Our founders were activists who wanted to shake up the humanitarian aid system. They wanted a form of action that was more challenging to governments. It is still very much part of our ethos.”

When, last April, MSF first challenged the World Health Organisation (WHO) over the impending calamity in West Africa, it was accused of alarmism. In May, as cases dipped, it looked as though the criticism might stick. But when the outbreak took off in June and July, MSF’s warnings were vindicated. Its leaders were incandescent.

In August, as the WHO finally declared the outbreak an International Public Health Emergency, Brice de la Vigne, MSF’s operations director, declared: “We have never faced a crisis on this scale.” Yet although MSF had been “screaming for months”, the global response had been “almost zero”. Instead of helping, leaders in the West had been “talking about protecting their own safety and closing airlines”.

MSF’s international president, Joanne Liu, was invited to address the United Nations Security Council in September, where she demanded military intervention, the first time the organisation had done so since the Rwandan genocide in 1994.

“Six months into the worst Ebola epidemic in history the world is losing the battle to contain it,” Dr Liu warned. She insisted member states use their expertise in biological warfare to tackle the epidemic.

“You have a political and humanitarian responsibility to immediately utilise these capabilities. It is imperative that states immediately deploy civilian and military assets with expertise in biohazard containment,” she said. The intervention worked. Although far too late, Britain is among countries who have dispatched military aid to the region and is building six treatment centres with 700 beds in Sierra Leone. But only one is so far open and “critical gaps” remain in all aspects of the response, “including medical care, training of health staff, infection control, contact tracing and epidemiological surveillance”, according to MSF.

In the past month, the first signs that the outbreak is slowing in Liberia have appeared, although it is far from under control. The situation is worse in Sierra Leone and Guinea, where new hotspots keep emerging. There is also disturbing news from Mali, where a nurse died last week and 75 people have been quarantined amid fears that the virus may not, as thought, have been contained. MSF has an Ebola team there, too.

The key to its swift response, according to Hawkins, is its funding. Over 80 per cent of its $1.3bn (£830m) global annual budget comes from private donations, with just 18 per cent from governments. No state funding is accepted in countries including Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq because it would be “detrimental to our security”, she says.

“Being financially independent means we make decisions about where to go. We don’t need to wait for governments to decide whether they have an interest,” she says.

MSF was highly critical of the way Allied Forces went into Afghanistan using humanitarian organisations as part of nation-building because it politicised the provision of humanitarian aid. But the organisation’s policy of standing apart, not just from governments but from other aid groups, has caused tensions, too.

Its allegation that it was left to respond alone to the Ebola crisis at the start of the outbreak in West Africa drew a sharp riposte from rival aid groups, who complained that MSF refused to water down its rigorous safety protocols by training others. Since then, MSF has been forced to relax its protocols as a result of the overwhelming need and has shared its blueprint for treatment centres and extended its training to include non-MSF staff.

In July, it published a report, “Where is Everyone? Responding to Emergencies in the Most Difficult Places”, in which it accused the UN and other aid organisations of becoming “trapped in their bureaucracies”, “avoiding risk” and [being] dependent on “geopolitical interests”.

But it did not exempt itself from criticism, noting that in some emergencies it had been “monopolistic” and too focused on hospital care and not enough on community outreach.

Ultimately, it depends on the continued willingness of volunteers such as Geraldine O’Hara to put themselves in harm’s way. Being single, it is her mother and sisters who suffer while she is away, she says. Shortly before her deployment to Somalia, she remembers a long conversation with the head of mission while she was shopping in a supermarket in Huddersfield, where her family lives, in which she learnt that were she to be kidnapped, MSF had a “no ransom” policy (two MSF workers were released earlier this year after 21 months in captivity in Somalia).

“I said to my mother this time, before I went to Sierra Leone, that I had only one enemy there – Ebola. In Somalia, I didn’t know who my enemies were. You have to acknowledge the risk. It sounds kamikaze, but MSF are incredibly careful with their planning. I go and do the work because I love it. The logistics and the politics, I leave to them.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments