Jacob Zuma: the rise and near fall of South Africa’s President

After seven years in office building a bulwark against his opponents by loading pivotal posts with his cronies – and avoiding answering charges of corruption and fraud – the leader of the ANC may yet stand trial

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.These are dark days for South Africa. Exports are falling; commodity prices are falling; the rand has slumped. The economy shrank by 1.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2016 alone: it is now only the continent’s third largest. Unemployment is at 26.7 per cent – an eight-year high – and business confidence is at its lowest for more than two decades.

Citizens are being urged to tighten their belts, drastically. But not everyone is suffering. Last month it emerged that the wives of president Zuma – he has four – have had 11 new cars bought for them in the past three years, for a combined cost of about 8.6m rand (£374,000). The money was supplied, helpfully, from the official budget of the police.

The President himself isn’t doing too badly, either. Months after the finance minister delivered a draconian austerity budget, the defence minister confirmed in May that the purchase will go ahead of a shining new presidential jet, whose value has been estimated at £1.75m.

After a decade of controversy, scathing court judgments, and allegations of political bullying and cronyism, the reputation of President Jacob Zuma seems to have hit an all-time low. A question that has been asked sporadically for years is now being asked constantly, in a deafening chorus of exasperation: how did Nelson Mandela’s dream of a ground-breaking democracy, of a prosperous, peaceful “rainbow” nation, come to be trampled on like this?

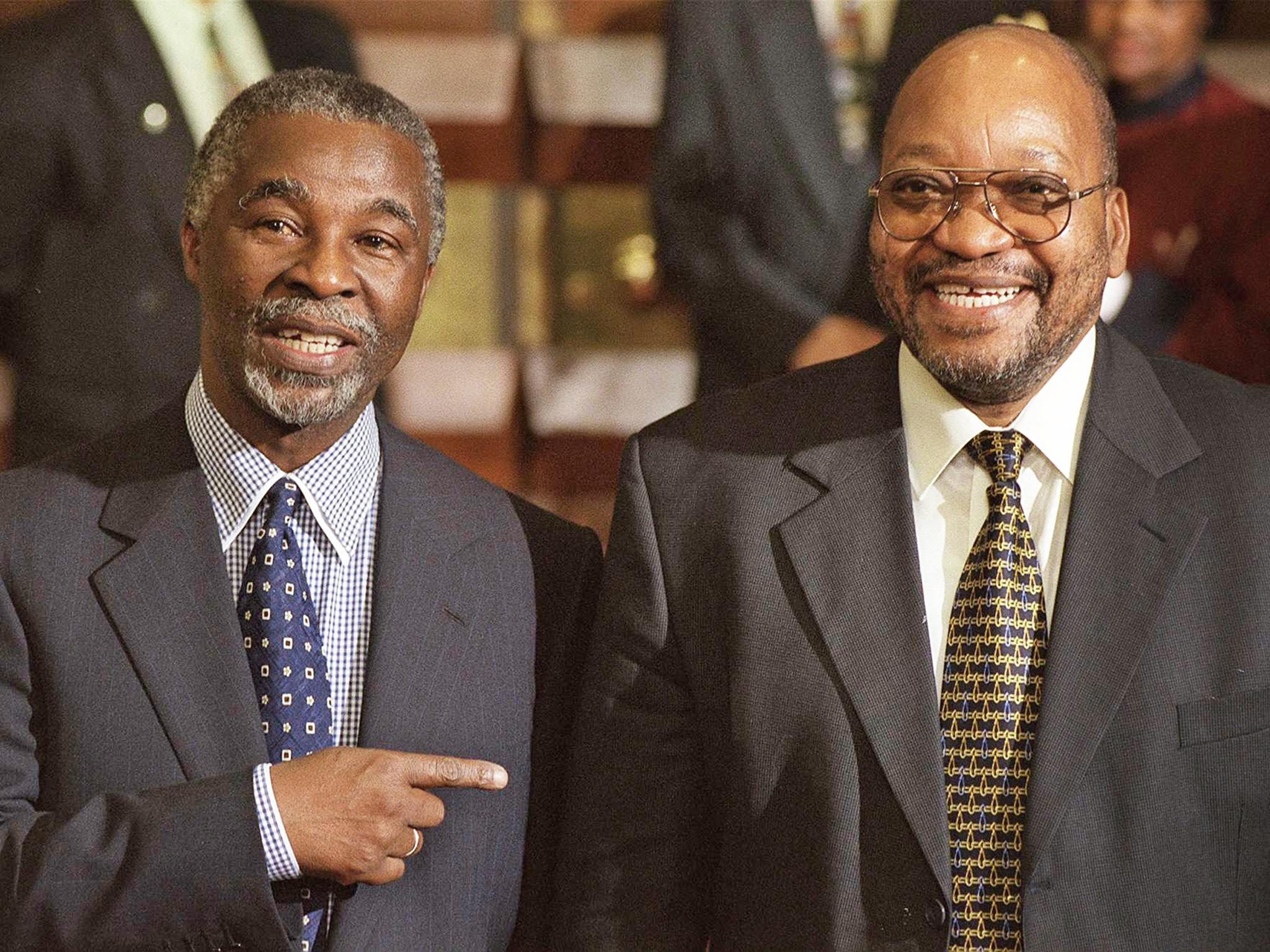

Zuma’s tortured journey to the top of South African politics began when he was made deputy president under Thabo Mbeki. It was a reluctant decision which Mbeki came to regret.

In 2005, a high court judge found Zuma’s financial adviser, Schabir Shaik, guilty of bribery. Zuma was the recipient of the bribes, but never stood trial.

Judge Hilary Squires nonetheless placed Zuma at the centre of his verdict against Shaik others, saying: “Since all the accused companies were used at one time or another to pay sums of money to Jacob Zuma in contravention of section 1(1)(a)(I) or (ii) of the Corruption Act and accused No 1 directed them to that end or made payments himself, all the accused are found guilty on the main charge on count 1.”

It was so damning a verdict that Mbeki, after a week of dithering, announced to Parliament that Zuma had been fired.

Zuma was then charged with raping a woman – the daughter of a friend at his home in Forest Town, Johannesburg. He was found not guilty after the accused was found to have provided unreliable evidence. Again a High Court judge, WJ van der Merwe, had strong words for Zuma, saying: “It is totally unacceptable that a man should have unprotected sex with any person other than his regular partner and definitely not with a person who to his knowledge is HIV positive.

"I do not even want to comment on the effect of a shower after having had unprotected sex. Had Rudyard Kipling known of this case at the time he wrote his poem “If” he might have added the following: ‘And if you can control your body and your sexual urges, then you are a man my son’.“

Zuma was assumed to be a political non-starter for the African National Congress. But to the astonishment of the political establishment, he successfully cast himself as the victim of Mbeki’s bullying and, after campaigning to win over the many factions disillusioned with the President, returned to the national stage in December 2007 to beat his rival in a bitter fight for the presidency of the ruling ANC.

A year later, Mbeki was removed from the presidency by the ruling party and Kgalema Motlanthe, a leader thought to occupy the middle ground, was installed for eight months. Zuma faced a swathe of corruption and bribery charges – more than 700 counts in all – and it was deemed unwise that he assume the presidency until they had been removed.

And, after mounting political pressure, the national prosecuting authority did just that, announcing that Mbeki had “interfered” with the prosecution process, rendering the charges illegitimate. Zuma was free to assume the presidency in May 2008.

No incoming president had been dealt as powerful a hand as Zuma since the days of the apartheid overlords. There were vacancies that had to be filled in all the key criminal justice institutions. He could appoint a new police chief; a new national director of prosecutions; a new head of the secret service; and the head of the new Hawks unit, which would replace the special police force, the Scorpions. In addition to this, the position of chief executive at the state-owned enterprises Transnet and SAA were vacant and he would be called on to appoint a new board to the South African Broadcasting Corporation.

It was a golden opportunity for Zuma to seize control of a range of pivotal institutions by placing political loyalty above competence. Keenly aware that he could still be brought to book for corruption in the future, Zuma set about establishing a shadow security state that would undermine the independence of the police and prosecutors.

One of Zuma’s first acts was to re-organise SA’s intelligence structures into one department, which was to fall under the control of a new intelligence minister, Siyabonga Cwele.

Bheki Cele, then a loyal supporter from Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu Natal, was made commissioner of police in July 2009, despite widespread misgivings about the appropriateness of his cowboy style for so serious a job. Another loyal lieutenant, Menzi Simelane, was made the national director of public prosecutions amid an uproar.

While director-general of justice, Simelane had testified at an inquiry into the fitness of Vusi Pikoli to hold office as prosecutions boss. The inquiry’s convenor, Frene Ginwala, had found that “in general his conduct left much to be desired. His testimony was contradictory and without basis in fact or in law.”

Zuma appointed Mo Shaik – the brother of his financial adviser, who had been convicted of corruption – as head of the secret service and Anwar Dramat as head of the new Hawks priority crimes unit. As insurance against any remaining instinct for independence, the unit was placed under the direct control of the police.

Unsurprisingly, the police, the Hawks and the directorate of public prosecutions showed no interest in pursuing the charges against Zuma – or any other high-profile ANC leader, for that matter. The sting had been taken out of the criminal justice system. But, in his haste to subdue this potential threat, Zuma had been careless.

The warnings about Cele’s “cowboy” style were proven true as he called on the police to take an aggressive “shoot-to-kill” approach to criminals. He awarded himself the rank of general and re-militarised the police ranks, which had been de-militarised under Mandela. Then, the South African Sunday Times revealed he had pushed through irregular lease deals for police premises in Pretoria and Durban. After a few months of prevarication, Zuma was left with no choice but to announce in June 2012: “I have decided to release General Cele from his duties.”

A few months later, in October, the constitutional court found Zuma’s appointment of Simelane was invalid. Judge Zak Yacoob read the ruling: “We conclude that the evidence was contradictory ... It raises serious questions about Mr Simelane’s conscientiousness, integrity, and credibility.”

When Shaik and Dramat’s loyalty came into question, they too were dropped. In Dramat’s case, the Hawks began to investigate him over the rendition of Zimababwean suspects who had been handed over only to be killed.

Zuma did not react to criticism of his poor appointment record. Instead, he replaced those who were made to resign or who were forced out with people he believed would be more loyal to him. Another Zuma appointment, Mxolisi Nxasana, would be forced to step down as prosecutions director in 2014 after it emerged he had previous brushes with the law.

Zuma knew his shadow security state would inevitably find itself in conflict with the constitutional dispensation. In anticipation of this, he moved to shore up his primary defensive weapon – parliament. He installed a loyal lieutenant, Baleka Mbete, as Speaker and packed the benches with MPs who would stay true to his cause. When they dissented, as veteran MP Ben Turok would over media legislation, Zuma forced him out.

Zuma attempted to muzzle the press in 2010 – barely a week after thousands of international journalists had left the country after covering the 2010 football World Cup – by announcing draconian “protection of information” legislation which would make it illegal for journalists to be in possession of leaked documents which “threatened state security” with a possible jail sentence of 15 years. Government officials would be able to designate material “classified” if they believed its exposure would compromise broadly defined “national security”.

At the same time the ANC released a “discussion paper” on a proposed “media appeals tribunal” that would oversee complaints about press reporting. The moves against the media followed sustained reporting on abuses of state money spent on construction of Zuma’s Nkandla residence.

Shortly before taking office, Zuma had stated that the status of judges of the constitutional court needed to be reviewed because they “were not God”. He sought to bend the constitutional court to his will, overlooking Dikgang Moseneke as chief justice in favour of Sandile Ngcobo when he was called on to make this appointment in 2009. Moseneke had made veiled criticisms of Zuma.

Zuma may have believed that Ngcobo would serve him as an ally (not for the first time, a mistaken assumption) because he had written a minority judgment in a case concerning him. In July 2008, the constitutional court had ruled that search and seizure warrants used by the Scorpions against Zuma and the arms company, Thint, were legitimate. Ngcobo had been the only judge to disagree.

When Ngcobo retired in 2011, Zuma again overlooked the politically unacceptable Moseneke, choosing to nominate Mogoeng Mogoeng for the top position. Mogoeng would preside over the landmark case against Zuma in 2016 – again showing the President‘s poor judge of character.

Faced with a constitutional court unwilling to become one of his political tools, Zuma turned on it once more. In a 2012 interview with journalist Moshoeshoe Monare, he questioned the court’s judgments. “We don’t want to review the constitutional court, we want to review its powers. It is after experience that some of the decisions are not decisions that every other judge in the constitutional court agrees with.

“There are dissenting judgments which we read. You will find that the dissenting one has more logic than the one that enjoyed the majority. What do you do in that case?” The judges were, he said “influenced by what’s happening and influenced by you guys”. By “you guys”, Zuma meant the media. The starkest illustration of Zuma’s poor judgement of who would serve his interests was his decision to elevate the softly spoken Thuli Madonsela to the position of public protector.

In all of these moves aimed at cowing the security machinery, closing down the space for free expression and subordinating institutions to his political will, Zuma has enjoyed the backing of the ANC. There were grumblings and dissent, but the party remained loyal. In 2014, Zuma moved to further shore up his political control of the security machinery by appointing Nathi Nhleko as police minister and the unknown David Mahlobo as state security minister.

Once in office, Madonsela showed her mettle when she investigated the biggest controversy of his presidency – the spending of some R256m of state money on his private homestead, Nkandla. Built on a hillside, the compound included numerous dwellings, an amphitheatre, swimming pool, a cattle corral, a chicken run and a “tuck-shop” to be run by one of his wives.

Madonsela found that Zuma should pay back some of the money spent as this could not be justified on security grounds. Zuma simply refused to pay, instructing his police minister, Nhleko, to conduct his own inquiry and Mahlobo to dig up dirt on Madonsela. The results were darkly comic.

Mahlobo instigated an investigation into Madonsela’s role as a “foreign intelligence operative”, while Nhleko produced a report which found Zuma did not owe a cent for the Nkandla renovations. The report was adopted with gusto by the loyal ANC MPs in parliament.

In December 2015, Zuma stunned the nation when he removed the highly respected finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, from office, replacing him with the completely unknown, Des van Rooyen, a back-bench MP.

This was too much, even for the usually acquiescent leaders of the ANC. After the rand plummeted against the dollar and European currencies and business, union and civic leaders united in expressing their horror at the decision, party leaders persuaded him to relent and three days later he was made to appoint Pravin Gordhan – a widely respected former finance minister – to the position instead.

When it emerged that Zuma’s business connections in the Gupta family had offered the deputy finance minister, Mcebisi Jonas, the position of finance minister, Zuma was exposed as having “out-sourced” cabinet appointments. Once again the party came to his defence, refusing to condemn him and instead initiating a lengthy process of disclosure behind closed doors at the party’s Luthuli House headquarters. It was a move designed to smother the controversy and it did. The party announced that few had come forward and the inquiry was quashed.

But, because of his failure to bend institutions outside of the security realm to his will, it was inevitable that Zuma’s shadow security state would eventually come into conflict with the constitutional democracy in which it lived an uncomfortable life.

It all came to a head this February, when Zuma was taken to court over his refusal to “pay back the money”. The case was brought to court by his arch-enemy, Julius Malema, whom he had fired from the party for dissenting over key policies. The verdict, delivered on 9 February, was devastating.

The chief justice Mogoeng drew a sharp line in the sand, informing Zuma that: “He is a constitutional being by design‚ a national pathfinder‚ the quintessential commander-in-chief of state affairs and the personification of this nation’s constitutional project.”

And, he said: “The president thus failed to uphold‚ defend and respect the constitution as the supreme law of the land. This failure is manifest from the substantial disregard for the remedial action taken against him by the public protector in terms of her constitutional powers.”

After a meeting of the party’s “top six” leaders, Zuma laughed off the judgment, refusing to take responsibility and apologising for any “confusion” that he may have caused. He proffered the bizarre defence that what he had done had been within the law at the time because the constitutional court had not yet ruled on it. Apparently, this legal nonsense was acceptable to the “top six” and ANC secretary-general Gwede Mantashe dutifully took to the podium to offer Zuma the “unanimous” support of the leadership.

Four days later, the ANC’s extended national working committee – a broader meeting of all the party’s leadership – lined up behind Zuma, saying there were no grounds for impeachment.

Even as they reaffirmed their faith in Zuma, the economy was shrinking by 1.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2016. Damaged by years of failed policy and Zuma’s inability to decide on a firm direction as he tried to please allies to the left and right, the economy was at its weakest point in a decade.

Under Zuma, South Africa’s once-vaunted mining sector had been destroyed by strikes and clumsy state-intervention aimed at rewarding his cronies that had deterred foreign investment. Unemployment reached an all-time high – the official figure was 26 per cent, but some put it as high as 35 per cent – as Zuma undid Mbeki’s careful policy of “fiscal discipline” in favour of opening the government coffers to spend on a bloated civil service.

In April 2016, Zuma was once more the subject of a scathing judgment, this time by Judge Aubrey Ledwaba in the High Court.

The opposition Democratic Alliance had challenged the dropping of corruption charges against Zuma and the court found: “Having regard to the conspectus of the evidence before us we find that Mr Mpshe [Mokotedi, former director public prosecutions] found himself under pressure and he decided to discontinue the prosecution of Mr Zuma and consequently made an irrational decision. Considering the situation in which he found himself, Mr Mpshe ignored the importance of the oath of office which demanded of him to act independently and without fear or favour. It is thus our view that the envisaged prosecution against Mr Zuma was not tainted by the allegations against Mr [Leonard] McCarthy [former head of the Scorpions]. Mr Zuma should face the charges as outlined in the indictment.”

After several weeks of silence, Zuma and the prosecuting authority announced that they would appeal against this judgment.

Ray Hartley works for Times Media Group

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

33Comments