Putin's Kremlin is hoping to use World Cup to bring Russia out of isolation

Rarely has a World Cup been more politicised, but Russia optimistic the tournament will mark a turnaround in its international fortunes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Vladimir Putin is not known to be a football fan, so it’s unlikely he knows the Shankly adage about it being more important than life and death. But if you were to look at his personal commitment to the 2018 World Cup project, you’d conclude the Russian president is living close to the former Liverpool manager’s principle.

In 2010, the then prime minister Putin headed a massive lobbying exercise to bring the tournament to Russia. He got the necessary votes with energy, persistence, and, if critics are to be believed, certain other assets too.

Eight years on and the Russian president is as invested in the tournament as ever.

On Saturday, the local organising committee unveiled the latest promotional video, one of a series that features the president. In it, a suited, smiling Mr Putin, with his back to the Kremlin, is filmed offering a branch of international friendship.

“For our country, it is a great joy and honour to welcome the international football family… we’ve opened our country and our hearts,” says the president, before switching to broken English: “Uelcome to Russia”.

It was an unusually cheery role for a man more at home in the land of suspicion and paranoia.

Mr Putin, no doubt, hopes the world can forget about politics for a month, and instead envelop itself in the enigmatic (mythical) charm of the Russian soul. The reality is likely to prove different.

The chemical attack on a Russian double agent and his daughter in Salisbury; the evidence of doping; the allegations of hacking; the hooligan attacks in Marseilles; the wars; the hunger striking prisoners and the continued the suppression of internal dissent – all of these look set to make the Russian 2018 World Cup the most politicised in living memory.

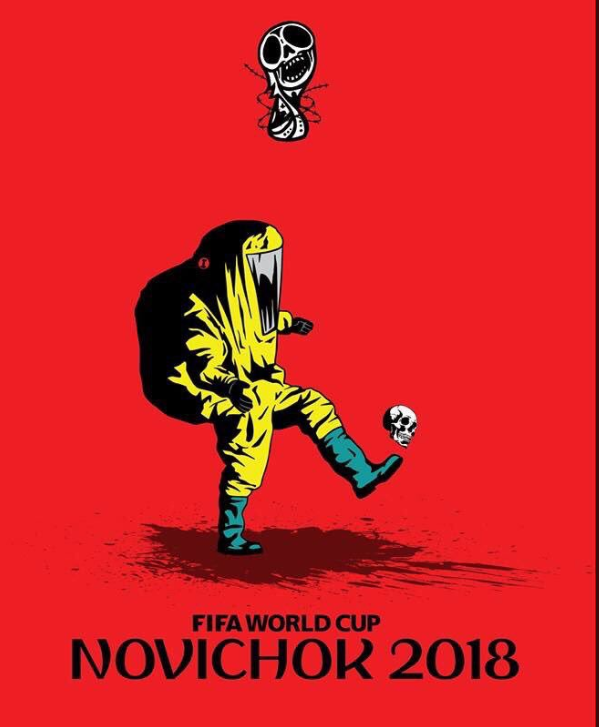

A series of memes doing the rounds on social media drives the point home. The images, which reinterpret official World Cup posters, show: Russia’s official mascot, Zabivaka the Wolf, with a severed arm in his mouth; a player doing keep-ups in a radiation suit with the title “Novichok 2018;” a goalkeeper, behind the “net” of a prison fence; and another, kicking a football in an upwards, seemingly rocket trajectory, towards a passenger jet.

Then there is the matter of how Russia persuaded the football world of its ability to host the event. Former prime minister David Cameron, who participated in the losing English bid, has been forthright in his criticism of the 2010 process.

He urged people to “fill in the blanks” on Russia’s success; the implicit suggestion being that bribes had played a crucial role.

Fifa’s own internal investigation into the affair failed to find a smoking gun, explicitly finding no evidence of collusion and bribery. But it also noted that the Russian bid committee had “made only a limited amount of documents available for review”. Computers had been removed, and hard drives had been wiped, with only soft explanations offered.

Allegations of corruption have dominated the story of post-bid construction, too.

For some well-connected people, it has been a very lucrative few years. Russia has officially spent $12bn (£9bn) preparing the tournament. The real figure is likely several billion higher, given VAT discounts and money spent from other regional budgets.

None of the major contracts were subject to open tenders, and it is unclear if the award process had any formal criteria whatsoever. The vast majority of the infrastructure contracts went to in-favour oligarchs, some of whom were longtime friends of the president.

All of that means that the Russian taxpayer likely spent at least 10 per cent more than they had to, said Ilya Shumanov, deputy director of Transparency International Russia.

“Russia already has a well established model for these type of projects, and a minimum of 10 per cent excess is the norm,” he say.

Few expect the project to return more than a fraction of the original investment. And given the nature of the post-Crimea economy, this is likely to be the last hyper-project for some time.

But despite the costs, no one in government is complaining, says Mr Shumanov.

Grand projects like these are oxygen to the blood of authoritarian regimes, he says: “On the one hand, it is the means to assign huge volumes of cash without any public oversight. On another, it is a way to raise national consciousness and the security state internally. And on a third, there is the opportunity to showcase the country externally”.

[Putin’s men] can see the World Cup as a good investment, a way to improve Russia’s standing. In any case, things can hardly get much worse

After a period of sustained isolation, the Kremlin believes it can use the tournament to capitalise on improved international conditions, says independent observer Konstantin Gaaze.

It sees that oil prices are inching up, ending immediate anxieties on budgets. It sees how on Iran and trade, Donald Trump has split western leaders, pushing them eastwards.

In Europe, it sees new friends it can talk to, with friendlier handshakes in Austria and France. Yes, Britain and Iceland will not be attending the official party, but a more widespread boycott has not caught on. President Macron couldn’t bring himself to join them. And rumour has it the Japanese emperor and maybe even Mr Trump will drop by for the big party.

“The president’s men feel their time has come again,” says Mr Gaaze. “They see the World Cup as a good investment, a way to improve Russia’s standing. In any case, things can hardly get much worse.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments