The women who risked their lives to uncover the crimes of the Holocaust

'There is a tendency to understand history as being about men and written by men,' says curator of new exhibition

A new exhibition sheds light on the work of women who risked their lives to record the atrocities of the Nazis – and who researchers say were overshadowed by their male colleagues.

The Wiener Library, the world’s oldest institution devoted to the study of the Holocaust, is tracing the stories and legacies of the individuals and institutions who first collected evidence of the extermination plot.

The new exhibition, which opens on Wednesday and runs until mid-May, includes the work of both those who carried out the vital work as genocide exploded around them and also those who pursued justice and remembrance much later on.

It includes some of the earliest eye-witness testimonies from Holocaust survivors ever to be recorded and explores the experiences of the “first generation” of Holocaust researchers who conducted their work in the face of Nazi efforts to wipe out all trace of Jewish existence from Europe.

“Under the most adverse conditions and often against indifference, denunciation and violence, they shaped the foundations of our current knowledge of the Holocaust,” researchers said in a statement.

It comes as evidence suggests holocaust denial is on the rise in the UK. A poll released last month claimed that more than 2.6 million British people think the Holocaust is a myth.

The study found some 5 per cent of UK adults do not believe millions of Jews were systematically murdered by the Nazis – with survivors and anti-racism campaigners saying this points to a “terribly worrying” level of denial.

The Wiener Library, which was founded in 1933, is the world’s oldest Holocaust archive and Britain’s largest collection on the Nazi era.

“There was implicit or explicit bias towards women,” Barbara Warnock, the curator of the exhibition, told The Independent. “There is a tendency to understand history as being about men and written by men. But this is being eroded and overturned and those tendencies are a lot more challenged as we become more conscious.”

“Sometimes very important individuals in Holocaust research such as Rachel Auerbach got overshadowed by men they were working with in how they were remembered. Women were more likely to be erased from the record.”

Auerbach was involved in Emanuel Ringelblum’s underground archive Oyneg Shabes – a secret organisation that collected evidence and documented Jewish life within the Warsaw Ghetto – and later established survivor reports as an important aspect of evidence about the Holocaust.

She ran a soup kitchen in the Warsaw Ghetto in the 1940s and worked for Ringelblum to help collect evidence and testimonies. In 1943, Auerbach managed to escape and survived the rest of the Second World War in hiding.

After the war, she continued the work of the Ringelblum Archive at the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland and ensured that parts of the archive were rapidly recovered from their hiding places.

She spent the rest of her life resolutely fighting to secure a place for victim’s survival experiences in the history of the Holocaust – seeing her commitment as a natural consequence of her own survival and as a responsibility towards those who were murdered by the Nazi Party.

Dr Warnock also cited the example of Ada Eber who conducted research into the Holocaust along with her husband Filip Friedman.

“But he was the person who had books in his name,” she explained. ”She has not been remembered even though she was instrumental in a lot of his work.”

They both worked for the Nuremberg trials in 1946 but researchers found there to be little trace of Eber, in comparison to the legacy left behind by her husband. They library has no photos of her and does not even know her date of birth.

Dr Warnock also drew attention to the work done by Dr Eva Reichmann, a prominent German historian and sociologist who fled Nazi Germany in 1939. Her husband, jurist Hans Reichmann, was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen following the November Pogrom in 1938 and credits his release to hours and hours of work by his wife.

Many women whose spouses or male family members were imprisoned fought hard to get the men released and to gather the necessary paperwork to emigrate.

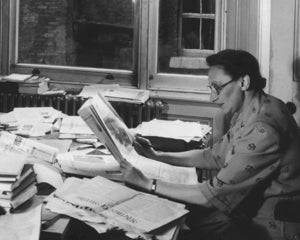

Reichmann worked for the BBC’s German Listening Service before joining the Wiener Library as director of research, where she led an ambitious effort to record eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust – including many hundreds of testimonies from Holocaust survivors.

She and her team gathered reports from refugees, survivors and others in Britain and abroad over the course of seven years.

“Holocaust denial makes it even more imperative for us to do this work,” Dr Warnock said. “It is ironic that people should deny one of the most well documented historical events.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks