What life looks like for refugees in France

'In hindsight I would sooner be fighting Daesh back home, making a difference. I have been here for six months and am bored and restless. There is no future here for us.'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I arrived at The Jungle camp in Calais one of the first things I saw was some graffiti on a slab of concrete spelling out the words “Fuck Journalist, Fuck The Police”. It turned out not everyone in the camp shared this sentiment, but once you feel the tangible sense of frustration and anger in Calais among the people in the camp, it soon becomes clear why a message like this would end up surfacing.

I want to share my experience of the camps in Calais and Dunkirk from ground level. I have been visiting the camps with fellow photojournalist Emily Garthwaite over the past few weeks (5 March for a few days and 18 March for another few days) . We wanted to understand the challenges posed for those who work and live around these areas and spoke with refugees, local policing authorities, the head of Calais commerce, medical teams, local residents and volunteers to try and grasp the bigger picture.

Upon arrival certain preconceptions we had about the camps were dispelled. For one, the living conditions in the Dunkirk camp were far more appalling than we anticipated. You can read about places like Dunkirk and even see photographs, but to go and see it first hand really hits home the gravity of the situation. The executive director of MSF UK (Doctors Without Borders) described the conditions as the worst she had seen in her twenty years of humanitarian work. Without a doubt the Calais camp is a tough place to live in, but the people living there are relatively fortunate not to be in Dunkirk. We were saddened to witness scenes that we could not believe were happening two and a half hours from London. Scabies, fever, even tuberculosis are present in the camps. There are children sleeping on mattresses pushed into the mud. They have no electricity or heating. This gloopy bacteria-ridden mud cakes everything, and is hard to keep out of the tents. Everything feels damp. We think of scenes like this to only be possible in far away countries, but it has been happening right on our doorstep.

MSF were only given permission in January to set up a new camp to replace the deplorable living conditions in Dunkirk. This meant that people had to live for months in squalor. Whilst the new site, which was opened on the 9 March, resembles a prison camp in many ways, the conditions are undeniably better. The wooden shelters are numbered and having an ‘address’ of sorts makes the people feel more dignified.

After speaking to many of the people living in the camps a recurring theme started to emerge. The people are not despairing over their current living conditions, but rather over the lack of certainty regarding their future. Some described the trauma of leaving their homelands, crossing seas with smugglers, and missing their families. We did not hear a single complaint about the mud, or the cold. Their anger seemed to be directed at a feeling of having no human rights or future prospects. We met refugees who left skilled work as engineers, tailors, photographers, teachers, journalists, musicians, students, surgeons, chefs, among many others kinds of work, who have been having to sit around for months unfulfilled. One young Iraqi man said to me, “In hindsight I would sooner be fighting Daesh back home, making a difference. I have been here for six months and am bored and restless. There is no future here for us.”

It is a common misconception that all refugees are poor. Many come from successful working backgrounds. To make the journey into Europe from somewhere like Iraq or Syria requires a substantial finical outlay. I met one family who came to France with €16,000, which represented all of their savings. They stayed in a hotel for as long as they could afford to whilst applying for asylum before running out of money. They were eventually forced to move into the camp in Calais. Another misconception is that all the people in the camps wish to stay in Europe. As mentioned before, many were forced to leave promising careers and their families behind to make the journey, and want nothing more than to return if it is safe to do so. We met plenty of refugees who described how their lives were directly at risk in their homelands, and who had no choice but to leave. One family showed us photos on a smartphone of their former life in Iraq only five months prior to arriving in the Dunkirk camp. On this phone we saw family scenes, selfies, dinners out, normal everyday things. War and violence came to where they lived, and they had to leave. Now all they have left of their former lives are cherished memories on a small screen, and the hope that one day they will be able to return home to live in peace. It is true that many of the refugees would like to come to the UK, the reason for this is that the majority can speak English, and feel they can integrate into British society easier than say going to a country like Sweden.

Keeping people in difficult living conditions for months on end with no work results in boredom and frustration. Violence is not uncommon in the camps, and I got the sense this is largely due to high numbers of young men with nothing to do and an unclear future venting their frustration when given an excuse to. If you put 8,000 Londoners in those kinds of conditions for six months, I am convinced that the result would be the same.

The Gendarmes and CRS police forces are not popular among the people in the camps. Their heavy-handed approach to quelling disputes, including employing tear gas, rubber bullets and using force to evict people from their shelters has resulted in a tense dynamic in the camps. I wanted to keep an open mind and talk to them myself before casting a concrete judgement. After doing so, I got the impression that not all are happy with what they are being asked to carry out, and some are sympathetic. Others did not come across this way, speaking of refugees in derogatory terms.

I understand that their jobs are stressful and difficult and that they have orders to maintain stability in the camps, often with the media watching, but after meeting a group of Iranian hunger strikers and hearing their story, I was dismayed to hear how inhumanely the police have acted at certain points.

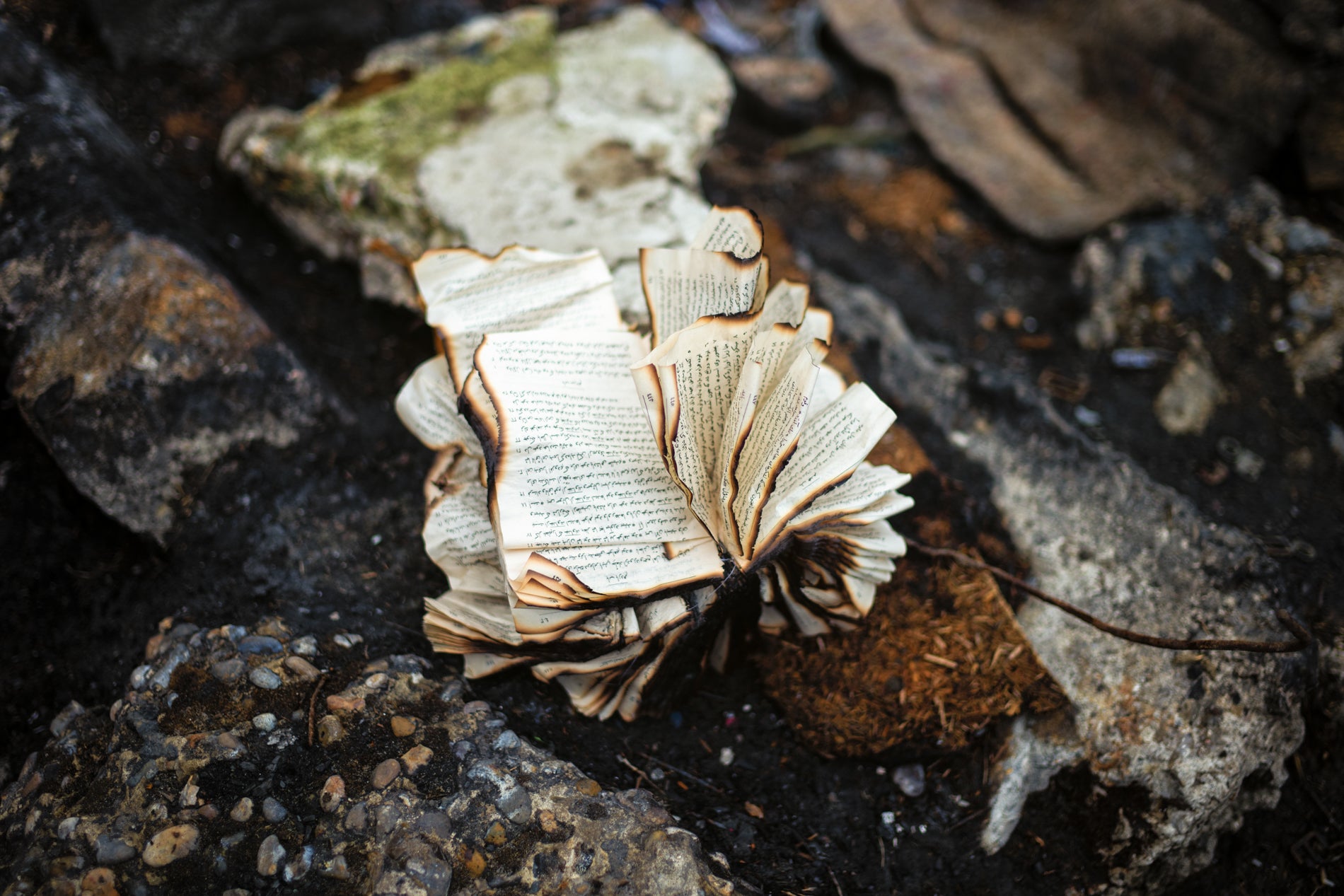

The lead up to their strike began when the prefecture announced that the 800 people living in the south side of the Calais Jungle were to be rehoused into 1,200 accommodations provided by the state. In reality, there were closer to three thousand people living in that part of the camp. A legal challenge was made to recognise this. The ruling from the court was fair and stated that there would be no use of force when evicting people, and no personal property was to be damaged. Soon after that announcement was made, the prefecture gave a day's warning to people to leave their tents and shelters. The following morning they came in with bulldozers and destroyed the shelters, and used force to evict those who hadn't already left. The Iranian part of the camp was the first to be razed. The Iranian people were so shocked that the legal ruling was being disregarded that some of them decided to go on hunger strike to demand that the eviction be stopped until all legal proceedings were complete. A second legal challenge was mounted when the evictions began, and few days after that a third challenge was sent to the European Court of Human Rights. We were told that the hunger strikers are Iranian Christian converts. Three of them had to flee Iran due to their Christian beliefs.

We met them nineteen days into their strike. One of them was a teenager, another an aeronautical engineer, another a tattoo artist. These are normal people who felt pushed to extreme lengths to have their voices heard. During the process of the hunger strike, all of the men had been offered deals to persuade them to stop. These included family reunions and being granted sped up asylum, something they no doubt wanted so much. The men turned down these offers however as they considered their cause to be about more than their own lives. They were willing to exchange their health for the chance to obtain fair legal treatment and human rights for all people in the camps. “Following the example of Jesus Christ, to sacrifice yourself for others is why we are doing this.”

The prefecture have made certain concessions since the strike was initiated including releasing a press statement promising that the north part of the camp will not be demolished. We were present in the shelter where the strike is taking place when this was announced by a sub prefect. I watched to see how this news would be received but men did not celebrate. The fight to get what they truly want is far from won.

The people in the camps are relying on the work of volunteers for distribution of clothing, food and medical assistance. Volunteers spend much of their time in warehouses sorting through donations, organising the transfer of supplies to the camps, as well as helping on site. I spoke to Care4Calais volunteer Alice Aedy. She said: “It astounds me to hear we are reluctant to improve the living conditions for the people as it might incentivise more people to come - our priority should be to decrease their suffering. We must acknowledge the current refugee crisis and treat these people with dignity. Regardless of political opinions, what is objective is the complete neglect that we see in the camps. I have met architects, interior designers, scientists…people who left a normal life. Many wish the war would end, as they are desperate to go home. I’m scared to see how history books will describe how once again, we turned a blind eye and looked the other way.”

This sense of compassion and a refusal to idly sit by knowing there are people suffering is what has prised many people away from their lives, families and jobs to go and volunteer. Some told us they spend weeks at a time helping.

MSF are providing medical aid but work out of a small shelter in the camp. Professionals present include physios, GPs, nurses and a psychiatrist. The unavoidable issue is that they are only available from Monday to Friday 10am to 4pm. Medical volunteers are providing extra support, working out of converted caravans on site. They are present every day. Because of the limited space they have been allocated they can only provide first aid. The necessary equipment for more serious medical treatment simply wouldn't fit in the caravans. For people needing urgent attention a nearby hospital in Calais has sectioned off a part of its A&E ward for refugees who are suffering more serious conditions. I spent some time following the medical volunteers around the camp to get a feel for what their work is like. There was a seemingly constant stream of people requiring aid. In a very short amount of time I saw a young boy with a heavy cough, another who had collapsed, a man with bad burns on his hand, a young man who had been blinded in one eye and an older man who was complaining of heart pain. The work is demanding, but from what I saw the medical volunteers are doing a fantastic job with the resources available to them.

Since the arrival of refugees in Calais, commerce in the area has been down 60%. This is bad news - at least in their terms - for restaurants, business owners and ultimately the locals. I spoke with the head of commerce in Calais, Pierre Nouchi who explained how this came about. Calais’ economy relies heavily on people from the UK coming through on holiday. Around the time that refugees began arriving in Calais, certain UK newspapers and those from other countries ran hostile scaremongering articles describing scenes of how Calais has been overrun by ‘migrants’ and potential ISIS militants. In truth, you can not tell at all by being in Calais town centre what is going on a short drive away. The streets and restaurants, whilst not bustling, appear to be populated by French citizens. It is worth noting that the camp in Calais has been built on a former toxic waste dump on the outskirts of the town. This site was clearly never intended to be observable or easily accessible from the centre, and this explains why the refugees and towns people do not cross paths very often. Calais is desperate to rebrand itself and to separate the image of suffering and poverty from its name. The longer negative associations surround the name Calais, the more Nouchi is concerned that things will get worse for local business in Calais and the people.

On one of the days we spent some time talking with the children in the camp. One of the questions we asked one 12-year-old Afghan girl was “do you like the food here?”. She replied, “no, because it is not my own.” Hearing this summed up so much of what it is truly like to live in these camps. She did not mean that she is ungrateful for having food provided for her, but her reaction was an honest one. She is homesick, feeling bewildered and vulnerable in an environment no child should have to endure anywhere in the world, let alone in modern day Europe.

To find out more and to donate to helping the refugees in the camp and the people supporting them, please visit: Care4Calais, Utopia 56, L'Auberge Des Immigrants, Hummingbird Project, Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments