‘I was born in war, I will die in war’: Trying to survive on Ukraine’s new front line

Russia’s war has now arrived in the Donetsk city of Kramatorsk, as Moscow vows to push further into Ukrainian territory. Bel Trew meets some of those living there, for whom every day is a battle for survival

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Olena and her husband Nikolai were trying to bury an elderly neighbour when the sky cracked open, spitting shards of shrapnel that split open their teenage daughter’s head.

Nikolai, 52, was a little further up the hill in the Ukrainian frontline village, and still holding the neighbour’s body, which he used to shield himself from the worst of the blast. Cowering under a corpse, he could only watch powerless with horror as his wife and his child Anastasia, 15, were shredded by the Russian strike in their own back garden.

Their village in Donetsk is quite literally on the front line of the ferocious war that started with Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February. Located just a few metres into patchily held Ukrainian territory, it may soon be engulfed by Russian troops, who have pressed on with an advance into Donetsk after capturing the whole of the adjacent Luhansk region.

And so it is a hellish no man’s land, where villagers cower in their basements as the tug of war rages above them.

“I was screaming Anastasia’s name, I was screaming Anastasia’s dead,” Olena, 51, says in tears from her hospital bed in Kramatorsk, a city that is itself under attack, around 18 miles south of the village. Medics tending to her say she received severe wounds to her head, arms and legs in the bombing, which took place the day before the interview.

“My daughter’s head had been cracked open; you could see her brain. She is my only child,” Olena adds before breaking off.

Comforting her is another of her neighbours, Olga, who oversaw Anastasia’s burial at dawn, only to be injured herself in shelling a few hours later as she tried to pick raspberries. Olga was ferried to Kramatorsk hospital, still concussed with a serious head injury.

“Every day a house is hit in our village by everything, even white phosphorus,” she tells The Independent shakily. “It’s too unsafe to properly bury people. Now we just wrap the bodies in a blanket and place them in holes in our own gardens.”

Stuck in the middle and fearful of repercussions from either side, the trio ask for their identities and the location of their village to be kept secret. They are reluctant to attribute blame for the violence, claiming they have been attacked from both sides.

“We just want peace... we want an end to this war,” Nikolai adds, desperately.

That is unlikely. This eastern slice of Ukraine is now the deadly focus of President Putin’s assault on the country.

On Monday he declared victory in Luhansk, the oblast adjacent to Donetsk, just one day after Ukrainian forces, severely outgunned, said they had been forced to withdraw from Lysychansk, the last remaining bulwark of resistance in the area.

The governor of now occupied Luhansk and the local authorities in Kramatorsk agree that seizing all of Donetsk is Moscow’s next objective. Cities like Kramatorsk and next-door Slovyansk – from where the evacuation of civilians is hastily being organised – are now in the line of heavy fire. There were reports on Tuesday that Russian positions were just a few kilometres from Slovyansk.

“The enemy already started ‘working’ with artillery and aviation in the Donetsk region. Most likely they will keep using the strategy of ‘scorched earth’, meaning first they will destroy and then attack,” Serhiy Gadai, the governor of Luhansk, tells The Independent. “The goal of the Russians is, and always was, to take the entirety of Ukraine. They will only stop where the Ukrainian army will halt them,” he adds.

Igor Eskov, a spokesperson for the local administration in Kramatorsk, says his city is preparing for the worst, expecting Russia and its affiliated forces to make a “pincer movement” on them, coming east from the recently captured Lysychansk and north from the territories beyond Slovyansk.

“After Mariupol, this is the biggest city left in Donetsk; it is the most important politically and strategically in the region,” he tells The Independent from outside the sandbagged local authority buildings. “Kramatorsk is the administrative centre for Donetsk. They are going to push to get as much territory as possible.”

Over the last few days, Moscow’s artillery have turned their turrets on the two key cities that lie just a few miles south of Olena’s village.

On Sunday, six people, including a nine-year-old girl, were killed and 19 wounded in the Russian hits on Slovyansk. Kramatorsk also came under fire. On Monday, while it is quieter inside the centre of the city, the summer afternoon is perforated by the continual whomp of shelling and outgoing fire.

And so at the hospital where Olena is being treated in Kramatorsk, which is receiving wounded from across the region, medics say they are understaffed, poorly equipped and exhausted. They are also worried that this is only the start, and that the front line will soon come to them.

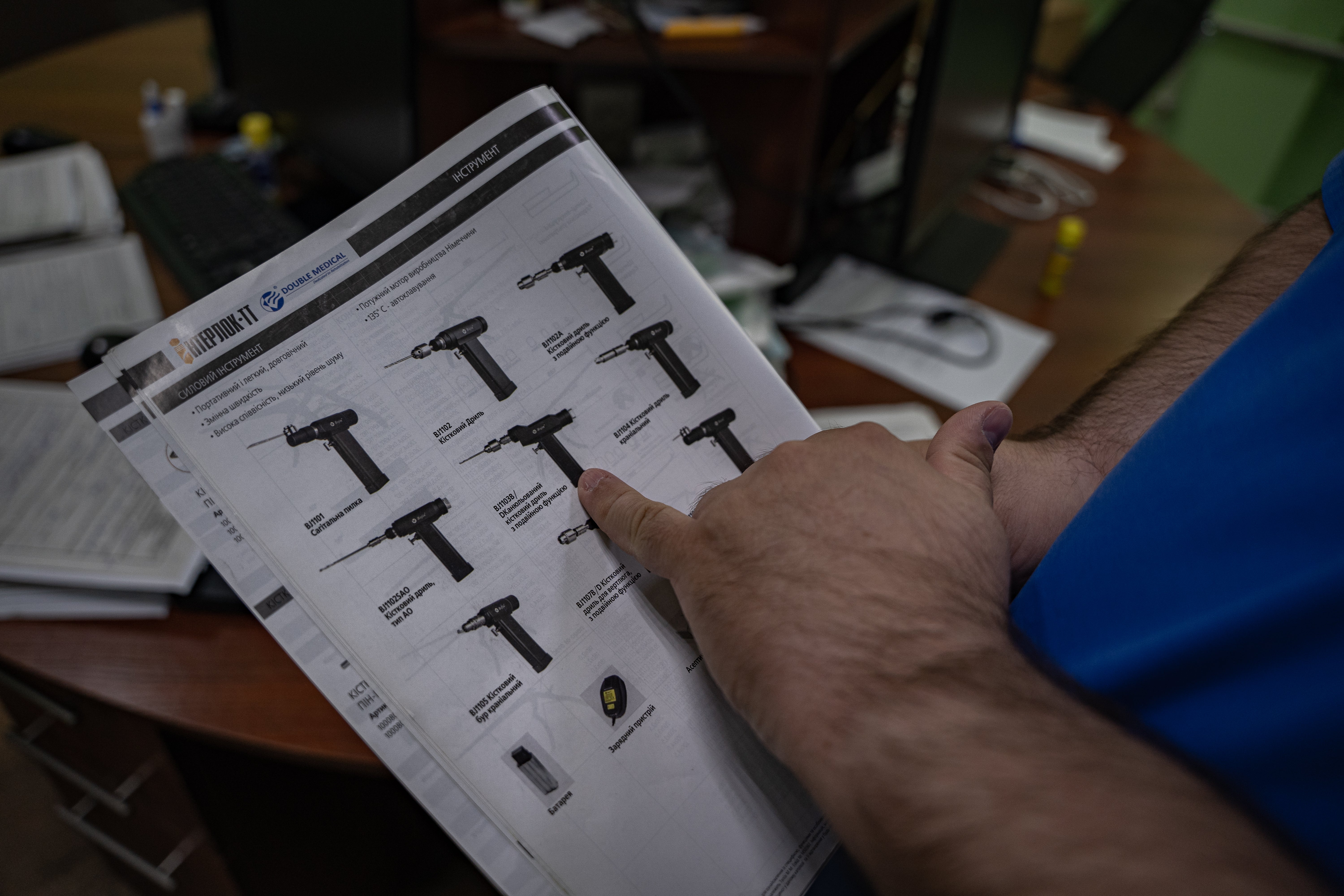

“I am working 24-hour shifts. Sometimes I try to nap but often I can’t,” says Vitali, a 46-year-old trauma doctor, found sitting dazed on a couch during a rare break. “We were doing orthopaedics before the war, now we are working with mine and shelling traumas. It’s totally different work. Our life is now cluster munitions.”

He says that he and his colleagues are having to improvise with some equipment. For example, before the war they hired surgical power-drills for orthopaedic surgery. Now they are forced to use household hand-drills on patients’ broken bones to fix implants. The companies that rented out medical equipment have stopped operating in Ukraine since the fighting erupted.

“We need new equipment and more staff. Cluster munition and mine injuries are happening very often,” Vitali continues.

“Just last week we treated a woman from Lysychansk, a grandmother who was taking care of her goat when she stepped on [a bomblet from a cluster munition]. Another man picked one up while collecting wood,” he adds.

Another problem stalking the population of Kramatorsk and the surrounding villages is hunger. Prices have rocketed since the war began, and salaries and even some pensions have stopped.

Against the sound of shelling and the wail of air raid sirens, residents of Kramatorsk queue for humanitarian aid. The vast majority are elderly.

They say they have been waiting for days just to get a bag of food and supplies provided by local and international NGOs. A single kilo of potatoes in the shops, they say, is the equivalent of $1 (84p), while their pensions are less than $100 a month now.

Olga, who is 85 years old and suffers from multiple health issues, has the number 707 scribbled on her arm – her position in the queue – to remind her when her turn is next.

This is her third day waiting outside the aid hub, and she stands leaning in the heat on her walking stick. She is afraid to leave Kramatorsk because of her health: she is not sure she could handle the journey. “The sound of the shelling is terrifying. I just stand behind two walls in the corridor, like the authorities suggest, and pray to God,” she says quietly.

Marina, 76, who is herself unwell and looks after a niece who has diabetes and is incapacitated, says this is her fourth day of queueing. Her husband and son have passed away, and so it is up to her to look after herself and her niece. She cannot leave Kramatorsk because her niece cannot move.

“I will come back at 4am tomorrow morning,” she says in desperation just before the hub closes for the day. “All we can do now is live in the basement.”

Behind her is Tamara, 82, who says she doesn’t have enough money to leave and has nowhere to go anyway. “I was born during the war and I’m going to die during a war. I never thought this is how I would spend my retirement,” she adds.

Inside the hub, exhausted volunteers say they are trying their hardest. A team of 10 is busy registering names and handing out food parcels arranged by a local organisation, called “Everything will be good in Ukraine”, and international food-aid charity World Central Kitchen.

“Daily we support around 500 to 600 people, but it is never enough,” says Igor, 55, who is coordinating the centre. Before the war, he worked in a steel factory that was later bombed. “The main problem is the rise in prices and the fact that almost everyone has lost their job. Now I’m worried the fighting will come here.”

He says the residents have repeatedly been asked to evacuate, but those who have stayed have nowhere to go, and no means of supporting themselves. Fights break out among desperate civilians when they have to close the centre for the afternoon.

“We always need more supplies,” he adds with a hopeless shrug.

The city around the hub, meanwhile, is eerily empty. The day before, the shelling was heavy in the centre, while now, the noise of shelling provides a constant backdrop.

In Kramatorsk hospital, Olena, Nikolai and Olga, stunned, like so many, say they have no plans for the future as they have no financial means to go anywhere and no support network.

Nikolai tries to comfort his sobbing wife Olena, vowing to adopt children orphaned by the war so they can rebuild their family. He says the fight has nothing to do with the civilians living through it, and that they just want to go home.

“We are just civilians; all we want is peace,” he adds with desperation, as his wife crumbles beside him.

“Let love win. What is happening is brother killing brother; let people learn to forgive each other. Let there be peace.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments