Turkish academics in apology to Armenians

Intellectuals break taboo to acknowledge genocide by Ottoman Turks

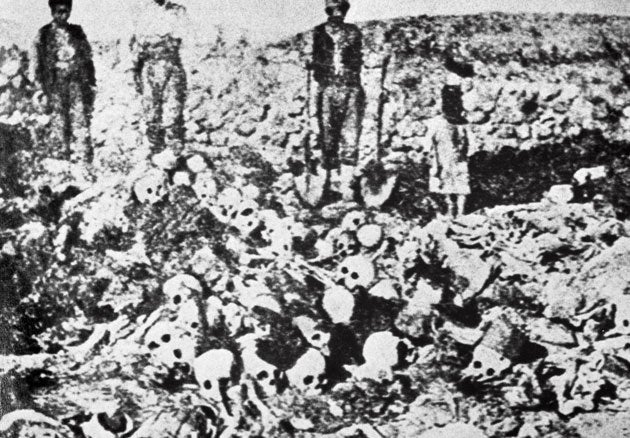

Around 200 Turkish intellectuals and academics are to apologise on the internet today for the ethnic cleansing of Armenians during the First World War, in the most public sign yet that Turkey's most sensitive taboo is slowly melting away.

"My conscience does not accept the denial of the great catastrophe that the Ottoman Armenians were subjected to in 1915," the text prepared by the group reads. "I reject this injustice and ... empathise with the feelings and pain of my Armenian brothers. I apologise to them."

Turkey accepts that many Armenians were killed during the collapse of the Ottoman empire, but insists they were victims of civil strife and that Muslim Turks also died. Most Western historians agree that the ethnic cleansing that killed roughly 700,000 Armenians amounted to genocide.

The academics are inviting Turks to sign a petition and add their voices to the apology. "Our concern is being able to look at ourselves in the mirror in the morning ... freeing ourselves by finally facing up to the past," said the political scientist Baskin Oran, one of the four organisers of the initiative.

However, nationalists have reacted angrily to the internet apology before it has even gone live, saying it is a national betrayal. Counter campaigns refusing to apologise have sprung up. The head of a nationalist party with 70 seats in parliament described the initiative as an example of the "frightening extent to which degeneracy and corrosion have spread".

The public apology coincides with a diplomatic rapprochement between Turkey and Armenia, whose shared border has been closed since the Nagorny-Karabakh war in 1993 and who have been locked in almost 100 years of hostility. President Abdullah Gul made history in September when he became the first Turkish leader to visit Armenia, and the two countries have been talking about restoring full diplomatic relations.

Publicly talking about what happened in 1915 remains a sensitive issue in Turkey. The Nobel Prize-winning novelist Orhan Pamuk was prosecuted in 2005 for saying a million Armenians had died. In January 2007, the Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink was gunned down by a nationalist teenager for advocating a more humane debate on the issue.

Yet, while almost every Turkish town has a street named after the chief organisers of the massacres, the taboo surrounding the Armenian issue is nowhere near as total as it was a decade ago. Bookshops sell books by Western and Armenian historians alongside texts written by defenders of the official Turkish thesis. Universities organise conferences on the issue. Istanbul galleries run exhibitions of postcards showing the central place Armenians had in the life of the late Ottoman Empire. And a 2005 memoir, My Grandmother, in which an Istanbul lawyer recounts her discovery that the woman who brought her up was born an Armenian, sparked widespread and sympathetic debate.

One of the first Turks to break the taboo was the historian Halil Berktay, who received death threats for months after telling a Turkish newspaper in October 2000 that he believed the Ottoman Empire committed genocide. Today, he is convinced the space for intelligent debate is growing. "Beneath the bluster," he says, "the Turkish establishment position is crumbling."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments