Turkey elections: Erdogan victory risks making country an authoritarian state sliding into Syrian mire

Crises at home and abroad are cross-infecting and tomorrow’s election looks unlikely to solve anything, writes Patrick Cockburn in Istanbul

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Turks vote on Sunday to choose a new parliament amid fears that Turkey is turning into an authoritarian one-party state and political, ethnic and religious polarisation is so great that the country is becoming permanently unstable.

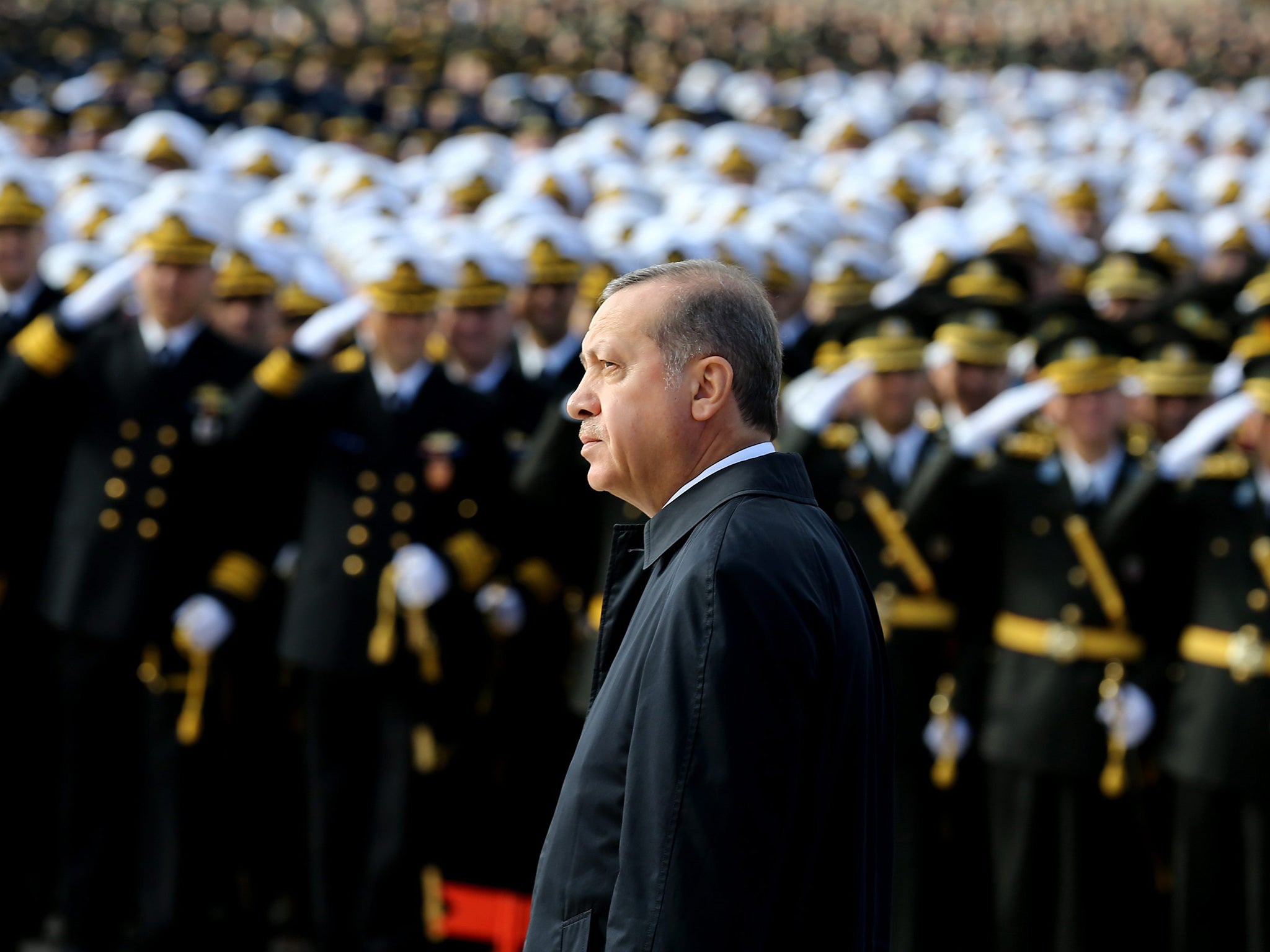

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP), in power since 2002, need to elect just 18 more MPs to win back the majority in parliament that they lost in the last election on 7 June. If they succeed, then Mr Erdogan will be able to expand his already extensive power over the state, security forces, media and judiciary.

The election outcome is too finely balanced to predict, according to the latest opinion polls, which show that as many as 50 million Turks are intending to vote. The AKP is expected to slightly increase its share of the votes to 42 to 43 per cent and the opposition Republican People’s Party’s (CHP) vote is forecast to rise to 26 to 28 per cent. The most important development of the last election was the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) getting 13 per cent – well above the crucial 10 per cent level that a party must reach to get representation in parliament.

The HDP’s success deprived the AKP of its majority and precipitated a five-month-long crisis in which this election is the latest, but probably not the last, episode. The AKP is unlikely to win back Kurdish support and is looking to take votes from the floundering right-wing anti-Kurdish Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to get at least 276 seats in the 550-seat parliament.

The election is taking place in an atmosphere of agitation and fear because of suicide bomb attacks on pro-Kurdish activists and demonstrators, which were blamed on Isis. The most recent attack, on 10 October in Ankara, left 102 dead. It was the worst terrorist incident in the history of Turkey and has led all parties, aside from the AKP, to cancel their campaign rallies.

The ability of the opposition to promote their policies was already limited by state television’s almost exclusive focus on Mr Erdogan and the AKP. Private media companies have been intimidated or taken over.

Voters interviewed by The Independent all speak of widening fault lines dividing Turkish society. Ismail Dogmusoz, a 29-year-old accountant originally from Mardin in southern Turkey close to the Syrian border, said that “divisions in terms of race, language and religion might deepen even further after the election.”

The rise of Isis and the proximity of a savage sectarian and ethnic civil war in Iraq and Syria is helping to poison the political atmosphere. Mr Dogmusoz cynically believes that, although polarisation of opinion may grow after the poll, violence might simultaneously decline if the AKP wins, because he suspects the ruling party of inciting or tolerating the upsurge in disorder to persuade Turks that the only alternative to Mr Erdogan and the AKP is anarchy.

But Mr Erdogan and the AKP are not solely or even mainly reliant for their political strength on partisan use of the security forces and judiciary, media bias, patronage and demagoguery. Elections in Turkey since 1950 have shown that there is a permanent centre-right majority, though it was for long constrained by military interventionism and by military coups. Though theoretically in power since 2002, the AKP only gradually took control of centres of power like the army, state apparatus, media and judiciary.

Having done so, it is not showing any mercy to its opponents. Nor does the AKP show restraint in enjoying the profits of power: Mr Dogmusoz says that the AKP treats the Turkish state as if it owned it and “they have spread to every position in it like a virus.”

But a 32-year-old clinical psychologist living in Istanbul, who did not want her name published, disagrees and said she intended to vote AKP because it represented stability while the politics of the other three parties simply amounted to saying that “they are against AKP and against Erdogan”. She added: “I don’t believe the Kurdish and Turkish nationalist parties can produce solutions for all citizens.”

The most telling argument for backing Mr Erdogan, according to the psychologist, is that “he turned Turkey into a middle-income country from being a low-income one.” She speaks enthusiastically of new roads, new bridges, new tunnels and new airports with cheaper air fares.

In saying that Mr Erdogan alone has the influence to negotiate an agreement with the Kurds, she is probably right but that does not mean that he is going to do so.

Zeynep Cermen, a journalist in her thirties living in Istanbul, wholly disagrees with this, saying that it is clear to her that Turkey is “evolving into an authoritarian state” and is being sucked into “the Syrian quagmire”. She sees extremism everywhere and is frightened by the growth of what she describes as nationalist fascism and claims support for Isis is at 10 per cent.

She says: “I would do anything to send my children to school abroad because the Turkish educational system is deteriorating.” Some parents attribute this to the government experimenting with more Islamic instruction in school. Ms Cermen is in despair over the decline in the status of women who she says are being harassed and criticised over everything from abortion to the way they laugh in public.

Her misgivings are echoed by Fatma, a 43-year-old professional in Ankara, who was shocked both when football crowds jeered during a minute’s silence for the victims of the Ankara bomb blast and when doctors who treated people beaten up by the police were imprisoned. Fatma complains that merit and expertise are ignored while “everything from high-level bureaucratic positions to large-scale construction projects are apportioned in a corrupt system of nepotism and cronyism, and every bit of injustice creates its own backlash.”

Perhaps the greatest danger facing the 78 million Turkish population is that crises affecting Turkey abroad and at home are beginning to combine and cross-infect each other. Thus, the relations between the Turkish state and the 15-20 per cent of the population who are of Kurdish ethnicity have become more antagonistic and violent over the past year. But this hostility is exacerbated by the war in Syria where the Syrian Kurds, once a marginalised minority, have set up their own quasi-sate called Rojava.

Isis has every incentive to increase ethnic and sectarian divisions in Turkey and is doing so successfully through its suicide bomb attacks. Kurds and some of the Turkish opposition accuse the government of creating conditions in which Isis can successfully operate. Drawing on its experience in Iraq and Syria, Isis is expert at carrying out atrocities that provoke a vicious circle of retaliatory killings and massacres.

The outcome of tomorrow’s election is unlikely to produce a clear-cut result, but even if it does, it may still not produce stability because divisions are too wide. Even the government’s takeover of much of the media seems to be having only a limited impact because people were already entrenched in their opinions. For the moment, Turkey exists in a state of permanent crisis

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

4Comments