What do Turkey’s election results mean and who will win the runoff?

Incumbent president Recep Tayyip Erdogan received most votes in weekend presidential election but cannot claim victory without majority support required for outright win

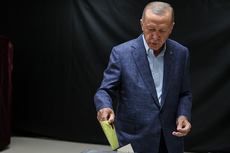

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan received the most votes in this weekend’s presidential election but failed to claim victory outright because he could not claim the majority support he needed to pass the magic 50 per cent mark.

Preliminary results showed the longtime leader had 49.5 per cent of the vote. His main challenger, opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, garnered 45 per cent, according to Turkish election authorities.

A third candidate, nationalist politician Sinan Ogan, received 5.2 per cent.

The election is being followed internationally to see the future direction of Turkey.

The strategically-located Nato member has cultivated warm relations with Russia, become less secular and tilted toward authoritarianism under Mr Erdogan, 69, who has made headlines of late by mediating Black Sea export negotiations since the Ukraine war broke out and by opposing Sweden’s application to join the North Atlantic military alliance. His defeat would certainly provoke alarm in the Kremlin.

Mr Kilicdaroglu, 74, has promised to re-orient the country as a democracy and is expected to adopt a more pro-Western stance, capitalising on frustration with an ongoing economic crisis and creeping authoritarianism to find a solid support base and was polling well in advance of Election Day before suffering a disappointing outcome.

“Don’t lose hope... We will get up and win this election together,” he has since tweeted, hoping to rally his supporters amid an atmosphere of gloom and dismay.

Mr Erdogan, much cheered by the result, told his own followers in Ankara: “The winner has undoubtedly been our country.”

The Supreme Electoral board said on Monday the results mean Mr Erdogan and Mr Kilicdaroglu will compete in a runoff election on Sunday 28 May.

Here is a look at Turkey’s two-round presidential election system and what happens next.

How does the two-round election work?

Mr Erdogan, who has strengthened his grip on Nato member Turkey since first coming to national power as prime minister in 2003, succeeded in changing the country’s system of government from a parliamentary democracy to an executive presidency through a 2017 referendum.

The change, which took effect after the 2018 elections, abolished the office of the prime minister and concentrated broad powers in the president’s hands.

It was therefore decided that the head of both state and government needed to receive more than 50 per cent of the vote to secure office in a single election. Since neither Mr Erdogan nor Mr Kilicdaroglu did that on Sunday, the two front-runners must face each other again in two weeks, while the third candidate is out of the running.

France and some other European countries use a similar process for electing presidents.

What part does the third candidate play?

Mr Ogan, 55, a former academic who was backed by an anti-migrant party, could become a “kingmaker” in the runoff now that he is out of the race. He has not yet endorsed either of the remaining candidates.

Turkish nationalists disgruntled with Mr Erdogan but reluctant to vote for Mr Kilicdaroglu, who had support from a six-party alliance and the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) appear to have accounted for most of Mr Ogan’s votes.

The far-right accuses the pro-Kurdish party of having links to outlawed Kurdish militants – an accusation the party denies. Mr Ogan has said he would not back any candidate “who doesn’t keep a distance with the terror organisation.”

Soner Cagaptay, an expert on Turkey at the Washington Institute think-tank, said most Ogan voters are likely to go for Mr Erdogan whether or not their original candidate endorses the Turkish leader.

“It’s certain that Mr Erdogan is going to sweep the second round,” Mr Cagaptay said.

What are the likely scenarios?

Mr Erdogan performed better than expected in Sunday’s election and the People’s Alliance led by his party retained a majority in Turkey's 600-seat parliament. Analysts say that gives the Turkish leader an edge in the runoff because voters may want to avoid having different factions running the executive and legislative branches.

Mr Erdogan said as much early on Monday.

“We have no doubt that the preference of our nation, which gave the majority in parliament to the People’s Alliance, will be in favor of trust and stability in the [second round],” the president told his supporters in Ankara.

Mr Kilicdaroglu, the leader of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), said he was certain of a second-round victory, but Sunday’s results indicate he could struggle to attract enough votes even though he was the candidate of the six-party Nation Alliance.

What to expect before the runoff

Analysts suggest the campaigning before the runoff could be brutal.

Before Sunday’s vote, Mr Erdogan disparaged the opposition as being supported by the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). At one rally, he showed hundreds of thousands of his supporters a faked video purporting to show a PKK commander singing an opposition campaign song.

“Information control was President Erdogan’s greatest asset in running and entering the election season. And I think his media loyal to him has successfully framed HDP support to Kilicdaroglu as ‘terrorist support,’” Mr Cagaptay said. “That helped scare away some nationalist voters.”

Mr Kilicdaroglu said Mr Erdogan had failed to get the result he wanted despite slinging “slanders and insults” toward the opposition. This has included the suggestion that Mr Kilicdaroglu is a proxy for Western powers.

That attitude was expressed by one of the president’s supporters, Ziya Uztok, 73, who confidently told the media: “Erdogan has stood strong for us Kilicdaroglu is an American project. I accept Kilicdaroglu as a fellow citizen, but I would not vote for him.”

Analysts also warned of economic turbulence in the next two weeks. Markets were watching the elections to see if Turkey would return to more traditional economic policies, as promised by Mr Kilidaroglu.

Experts say Mr Erdogan’s economic policies, which ran contrary to mainstream theories, led to the country’s currency crisis and soaring inflation.

The Turkish stock exchange, Borsa Istanbul BIST 100 index, dropped 6.2 per cent at Monday’s opening before recovering some ground.

“Turkey’s political destiny remains on hold until the second round, scheduled for 28 May,” said Bartosz Sawicki, market analyst at financial services firm Conotoxia.

“[The outcome will] determine whether Turkey will continue down the path of unorthodox, imbalance-increasing policies or whether, after 20 years, it will return to a path of reform and recovery using methods more in line with economic textbooks.”

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks